The Curiosity of Cats

When the musical opened on Broadway, 25 years ago, few predicted its amazing success—or what it would mean for composer Andrew Lloyd Webber

Even for Broadway, it was a grand opening—and a grander gamble. As audiences poured into the Winter Garden Theatre on the evening of October 7, 1982, for the American première of Andrew Lloyd Webber's Cats, they knew they were getting a first look at the hot new dance musical that had swept London. Many even knew that the show was opening to the largest advance sale in Broadway history—$6.2 million. For months, they had been bombarded by publicity, with a cat's-eye logo peering out enigmatically from T-shirts, watches and billboards. "Isn't the curiosity killing you?" asked the voice-over on a television commercial before the show opened. And the answer was yes.

Still, they had no idea that the show they were about to see had already saved Lloyd Webber from financial peril and was about to transform him into the laird of a theatrical realm that, at its height, commanded stages from London to New York to Hamburg to Vienna to Tokyo. By the time Cats closed, on September 10, 2000, after 13 previews and 7,485 performances, the "megamusical" had been born and Andrew Lloyd Webber's domain had become the latter-day equivalent of the old British Empire, upon which the sun never set.

Twenty-five years later, the miracle of Cats continues to resound. On its propellant, Lloyd Webber became the first composer ever to have three shows running simultaneously in the West End and on Broadway, a feat he accomplished twice. Knighted in 1992, he was given an honorary life peerage five years later as the Right Honourable the Baron Lloyd-Webber of Sydmonton Court, his estate about 90 minutes west of London. In personal wealth, he has vastly eclipsed his boyhood idol, Richard Rodgers, with a fortune estimated at more than a billion dollars, homes in London and Sydmonton, a castle and horse farm in Ireland, an apartment in the Trump Tower in New York City and a villa in Majorca.

(A note about the hyphen: as a young man, Lloyd Webber's father, William, added the "Lloyd" to his name to distinguish himself from W. G. Webber, a rival organist at the Royal College of Music. And while the young Andrew occasionally hyphenated his name in correspondence, his baronial title is the only place it is hyphenated today, as British titular custom mandates a hyphen when there is a double surname.)

The day of the blockbuster megamusical—defined by Jessica Sternfeld in her excellent study, The Megamusical, to include such larger-than-life shows as Lloyd Webber's Cats, Starlight Express and The Phantom of the Opera; Boublil and Schönberg's Les Misérables and Miss Saigon; and Chess, by Benny Andersson and Björn Ulvaeus of ABBA, and Tim Rice—may at last be over, but Lloyd Webber's transmogrification from skinny, long-haired counterculture icon to well-fed and tonsured Tory peer personifies the triumph of the baby boomer as few other careers do.

But as the pussycats frolicked on that autumn evening in New York, most of this was still in the future. No one could have predicted that Cats, which had begun life very modestly as a song cycle performed in the composer's private theater in a converted chapel at Sydmonton, would prove to be the longest-running show in Broadway history (later surpassed by Phantom). Nor could anyone have foreseen that it would represent such a conflict between art and commerce—a Hobson's choice that has bedeviled Lloyd Webber ever since.

The show's fate was far from assured. A dance musical based on minor poems by T. S. Eliot? And what did the British know about Broadway-style dancing? That was America's preserve, lorded over by Gower Champion and Bob Fosse and Jerome Robbins. As for Lloyd Webber, he was best known as the other half of the Tim Rice partnership. They had had a hit record—and a Broadway flop—more than a decade earlier with Jesus Christ Superstar and a succès d'estime, under the steady hand of Hal Prince, with Evita, which also had started life as a rock album.

So the prospects for Cats were not great, as Lloyd Webber knew. "I can give you the objections, and they sound a convincing lot," he would recall. "Andrew Lloyd Webber without Robert Stigwood [the flamboyant impresario who had produced Superstar], without Tim Rice; working with a dead poet; with a whole load of songs about cats; asking us to believe that people dressed up as cats are going to work; working with Trevor Nunn from the Royal Shakespeare Company, who's never done a musical in his life; working in the New London, the theater with the worst track record in London; asking us to believe that 20 English people can do a dance show when England had never been able to put together any kind of fashionable dance entertainment before. It was just a recipe for disaster. But we knew in the rehearsal room that even if we lost everything, we'd attempted something that hadn't been done before."

In 1980, the year before Cats opened in London, Lloyd Webber had mortgaged his beloved Sydmonton Court for the second time (he had bought it with the fruits of the Superstar album's success) to raise nearly $175,000 for his own show. Cats' young producer, Cameron Mackintosh, needed $1.16 million to stage it, but no one with means wanted to back it. So Mackintosh advertised in the financial press, soliciting small investments—750 pounds (almost $1,750) was the minimum. In the end, 220 people put up money for the show, including a man who wagered his life's savings of just over $11,000. They all profited handsomely, Lloyd Webber most of all.

Going into the London tryouts, however, Cats lacked the crucial ingredient of all successful musicals: a hit song. Mackintosh needed it. Nunn, the director, demanded it for Grizabella, the bedraggled Mary Magdalene cat who achieves her apotheosis as she ascends to the Heaviside Layer at the show's climax. It was up to Lloyd Webber, the composer, to write, borrow or steal it—even if only from himself. Thus was born "Memory."

Composers never throw anything worthwhile away, so even when a musical dies stillborn, parts of it find their way into other shows. (Rossini liked his overture for La gazza ladra so much he used it in at least two other operas.) Years before, Lloyd Webber had toyed with writing an opera about the competition between Puccini and Ruggero Leoncavallo, who wrote different versions of La Bohème. (Puccini's has held the stage since its première, in 1896; Leoncavallo's, which premièred the following year, has all but vanished, and its composer's reputation today depends almost solely on his one-act opera, Pagliacci, most often seen with Pietro Mascagni's Cavalleria Rusticana—the "ham 'n' eggs" of double-bill legend.) Nothing ever came of Lloyd Webber's Bohème project, however, and the music he had sketched for it wound up in a bottom drawer.

Now it came out, in the form of the tune for "Memory." The first person Lloyd Webber played it for was his father, Bill, a noted church organist and minor British composer of the mid-20th century. Lloyd Webber waited anxiously for his father's judgment: "Did I steal it?" he inquired, fearful that the catchy melody, underpinned by a distinctive, falling-thirds harmony, might have originated in some other composer's oeuvre, half-remembered and now, however unwittingly, regurgitated.

Bill just shook his head and said, "It's going to be worth two million dollars to you, you fool." Shortly thereafter, Lloyd Webber played it for Nunn, who asked what it was. "It's a very extravagant, emotional theme," Lloyd Webber told him. "Make it more emotional, more extravagant, and we'll have it in Cats," said Nunn.

And so they did. When Lloyd Webber played it for the cast, Nunn turned to the performers and said, "What is the date? The hour? Remember, because you have just heard a smash hit by Lloyd Webber."

In a poignant example of what-might-have-been, Tim Rice took a crack at writing the words, in part because his mistress, Elaine Paige, had suddenly replaced Judi Dench as Grizabella, and in fact his words were used for a long stretch in rehearsal. (Although married, Rice was carrying on a very public affair with Paige.) But in the end his lyric was replaced by one written by Nunn (who used Eliot's "Rhapsody on a Windy Night" as his starting point), and Rice had to watch millions in publishing royalties slip away. The rejection only further soured Rice's already precarious relationship with his former partner.

And what of the melody itself? A standard criticism of Lloyd Webber, especially from drama critics, is that his music is derivative—a gloss on his betters when it is not an outright theft. Since most drama critics are, to put it charitably, nonmusical, this is an odd criticism, and one that smacks of received opinion: "Puccini-esque" is a term one encounters often in criticism of Lloyd Webber's music, but aside from "Growltiger's Last Stand," which parodies the first-act love duet from Madama Butterfly, there is precious little Puccini in Cats.

Indeed, Lloyd Webber has always been more highly regarded by music critics, who not only know the repertoire he is alleged to be pilfering, but also can place him correctly in a dramatic-operatic context. Far from being the love child of Puccini and Barry Manilow, as some would have it, Lloyd Webber is more correctly seen as a kind of latter-day Giacomo Meyerbeer, the king of the Paris Opera in the mid-19th century, whose name was synonymous with spectacle. But a little ignorance goes a long way, and with "Memory" the notion that Lloyd Webber is a secondhand pastiche artist—if not an outright plagiarist—got its start.

This is partly Lloyd Webber's own fault. His melodies sometimes skirt perilously close to earlier classical and Broadway sources, and while the showbiz axiom that "good writers borrow, great writers steal" may well apply, it is also true that some of his tunes, both large and small, evoke earlier sources. As drama critic John Simon wrote after the première of Phantom: "It's not so much that Lloyd Webber lacks an ear for melody as that he has too much of a one for other people's melodies.... I predict that Gershwin and Rodgers, let alone Puccini and Ravel (another of his magnets), have nothing to fear from him." Other critics have been less subtle: "Webber's music isn't so painful to hear, if you don't mind its being so soiled from previous use," wrote Michael Feingold of the Village Voice.

So, are the critics right? Is Lloyd Webber a kind of musical ragpicker, offering secondhand tunes at first-rate prices? Certainly, there is more than enough aural evidence to support such a claim. The melody in The Phantom of the Opera at the words, "And in his eyes/all the sadness of the world," is closely related to Liu's suicide music in the last act of Puccini's Turandot. (Yes, this bit is "Puccini-esque.") The opening theme of the revised Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat bears a striking resemblance to the piano tune Magnolia is practicing aboard the Cotton Blossom in Jerome Kern's Show Boat. The thundering chromatic chords that open Phantom are the spiritual heirs of the first notes of Ralph Vaughan Williams' London Symphony.

But it's far too facile to dismiss Lloyd Webber as an imitator. Plagiarism entails much more than mere correspondence of notes; the test of actual theft involves whether the same sequence of notes (there are, after all, only 12 of them) functions in the same way as in the source material. That is to say, does it have the same dramatic and emotional function?

Neither music nor melodies arise or exist in a vacuum. Irving Berlin was accused by none other than Scott Joplin of having stolen the theme of "Alexander's Ragtime Band" from the final number of Joplin's opera, Treemonisha, the deeply moving "A Real Slow Drag." (Berlin was probably innocent.) Early Richard Rodgers owes a clear debt to ragtime, as does the music of Harry Warren, the great Warner Bros. composer and songwriter. Lloyd Webber's case is even more complicated.

From his father, he absorbed the whole spectrum of British art music, from Thomas Tallis to Sir Edward Elgar and Ralph Vaughan Williams. His younger brother, Julian, has had a successful career as a classical cellist. And Andrew's own predilections led him, after a life-changing exposure to the movie South Pacific in his youth, to Broadway. Coming of age in the 1960s (he was born on March 22, 1948), Lloyd Webber drank deeply at the trough of rock 'n' roll, internalizing its harmonies and rhythms and spitting them back out again in Jesus Christ Superstar. Lloyd Webber is a musical sponge, promiscuously soaking up influences that include not only music, but Victorian art and architecture as well. Politically conservative, he's the quintessential Tory, adrift in a tsunami of cultural and demographic change, desperately clinging to what made Britain great.

But does that make him a plagiarist? Absolutely not.

"Memory" turned out to be a big hit and a best-selling single for Barbra Streisand. It is, however, anomalous among Lloyd Webber's output for the simple reason that Lloyd Webber does not write songs, he writes shows. Of course, the shows are made up of individual numbers, but the very scarcity of "hit" songs from Lloyd Webber productions—quick, name another besides "Don't Cry for Me, Argentina"—sets his shows apart from those of Irving Berlin and Rodgers and Hammerstein. He has long (since Superstar, in fact) protested that he doesn't write musicals, he writes operas, and it is long past time that critics take him at his word.

Through the years, Lloyd Webber's most prominent American critic and chief antagonist has been Frank Rich, the former drama critic of the New York Times. In his time on the drama desk, the "Butcher of Broadway," as he was known, was notorious for working political references into his reviews; today, he works showbiz references into his weekly political column. Like most drama critics, Rich had minimal qualifications to pronounce judgment on musical matters, which did not stop him from trying. (On Aspects of Love: "[T]his time the composer's usual Puccini-isms have been supplanted by a naked Sondheim envy.") In time, relations between Lloyd Webber and Rich grew so acrimonious that when the composer acquired a racehorse, he named the beast after the scribe. "That way, if it falls, we won't mind," explained Lady Lloyd-Webber.

So it may come as a surprise that Rich gave Cats, on balance, a favorable notice, one that had everything to do with the show's theatrical values and nothing to do with its music: "[Cats] transports its audience into a complete fantasy world that could only exist in the theater and yet, these days, only rarely does. Whatever the other failings and excesses, even banalities, of Cats, it believes in purely theatrical magic, and on that faith it unquestionably delivers."

Still, to attribute the initial success and staying power of Cats to its junkyard setting and levitating tire is to miss the point. Audiences were thrilled by the crashing chandelier that ends the first act of Phantom, but no one hums a crashing chandelier or buys an original-cast album because of it. Lloyd Webber's music stays in the popular imagination in spite of its origins in megamusicals, not because of them. As noted, Superstar and Evita both began life as rock double albums (as did Rice's Chess), and in that form they will outlive their theatrical incarnations and "original-cast" albums.

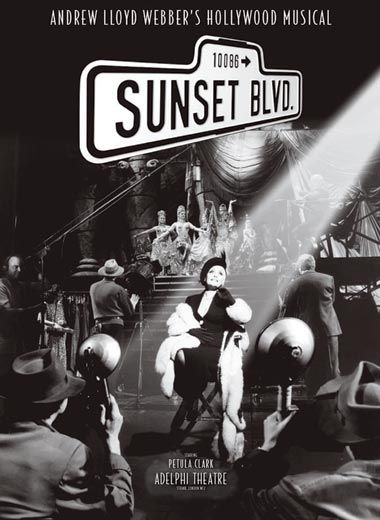

But no one stays on top forever, and it's entirely possible that Lloyd Webber's long stint at the heights of the West End and Broadway is over. His last international hit—Sunset Boulevard (1993)—was preceded by the relative failure of Aspects of Love (musically, his finest work) and followed by a string of flops, including Whistle Down the Wind, The Beautiful Game (neither of which made it to Broadway) and The Woman in White. Even Sunset, which opened with the largest advance sale in Broadway history and won seven Tony Awards, failed to recoup its investment.

Which naturally gives rise to the question: Is he finished?

It seems all but certain that the megamusical is finished. Enormously expensive to mount, the genre had a great run lasting nearly a quarter of a century, but despite the recent revival of Les Miz, it does not appear to be coming back anytime soon. Boublil and Schönberg's more recent works—Martin Guerre and The Pirate Queen—have not replicated the success of their earlier works. And after a brief flurry of interest, the shows of Frank Wildhorn (Jekyll & Hyde, The Scarlet Pimpernel), sometimes referred to as "Lloyd Webber Lite," have faded from the scene. Although reports of the death of Broadway inevitably turn out to be exaggerated, its creative energy seems to have departed once again, leaving a trail of revivals—not only Les Miz, but also Grease, Sondheim's Company, Kander and Ebb's Chicago and Marvin Hamlisch's A Chorus Line—and such cobbled-together shows as Mamma Mia! (based on ABBA songs from the 1960s and '70s) and Jersey Boys (Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons), designed to appeal to aging boomers eager to relive the music of their youth. The only spiritual heir of Lloyd Webber still chugging along is the Walt Disney Company, whose stage spectaculars Tarzan, The Lion King and Beauty and the Beast owe much to Lloyd Webber's trailblazing.

Andrew Lloyd Webber will turn 60 in March. After two unsuccessful marriages—to Sarah Tudor Hugill, with whom he had two children, Nicholas and Imogen, and Sarah Brightman, the original Christine Daaé of Phantom, who, post-parting, has gone on to a career as a pop diva—the composer has found stability and happiness in his 1991 marriage to the former Madeleine Gurdon, an equestrienne who has borne him three children, Alastair, William and Isabella. Unlike the reclusive Sarah I or the flamboyant Sarah II, the no-nonsense Lady Lloyd-Webber of Sydmonton is at once lover, wife, helpmeet and business partner. Her husband's former indulgences, especially in fine wines, are largely a thing of the past, and his old crew of bibulous hangers-on has been replaced by savvy business folk and crisp personal assistants who administer the Empire from the offices of Lloyd Webber's company, the Really Useful Group, on London's Tower Street. It's quite possible that the old hunger has long since been assuaged, the creative fires banked.

And yet . . . for years Lloyd Webber has been talking about forsaking mere commercial considerations and embracing art as his one true mistress. This usually occasions a round of sniggers from those who understand neither the man nor the music, but there can be no doubt that, if he put his mind to it, Andrew Lloyd Webber could yet write a show, or an opera, of undeniable artistic worth.

In a sense, he already has. Those lucky enough to be present at Sydmonton to hear the first run-through of Aspects of Love in July 1988 will never forget the sheer, overwhelming beauty of the music (played on two pianos); there, at its very first performance, the show had already found its ideal form. Onstage, however, the show simply did not work. This was partly the fault of the set designer, the late Maria Björnson, whose brilliant aesthetic for Phantom here seemed leaden, earthbound, depressing. It was also partly the fault of the director, Trevor Nunn, who saw David Garnett's Bloomsbury-era novella of sexual high jinks as an opportunity for social commentary. It was also partly Lloyd Webber's fault; given the opportunity to finally come out from behind the Phantom's mask and show his face as a serious artist, he compromised his musical vision by tarting up the score with false climaxes and showy endings.

Andrew Lloyd Webber approaches his 60th birthday as something of an anomalous figure. Successful by any conventional measure, wealthy, the bearer of his country's highest honors, he has become a kind of dilettante in his own profession, conducting his own star searches on British television ("How Do You Solve a Problem like Maria?" and "Any Dream Will Do") for unknowns to cast as leads in Lloyd Webber-produced revivals of The Sound of Music and Joseph. Lloyd Webber even popped up on American television last winter as a judge on the Grease: You're the One That I Want talent search, an experience that so frustrated—or inspired—him that in July, he announced he was signing with the Hollywood talent agency William Morris Associates to look for an American television network deal for a star search. Between the House of Lords and appearing at the likes of a memorial concert for Princess Diana in July, he doesn't ever have to write another note.

Still, the young boy Bill Lloyd Webber dubbed "Bumper" for his restless—and occasionally reckless—curiosity is likely to reassert himself, as Lloyd Webber chases the one thing that's always eluded him: critical respect. For a time, the odds-on favorite for his next project was Mikhail Bulgakov's Soviet-era allegory, The Master and Margarita, a cult work much admired by Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, who has read it in the original Russian as well as in English. Featuring Satan as a major character, the novel circulated underground in the former Soviet Union and was not published until 1966, more than a quarter of a century after Bulgakov's death.

The fantastic source material and the religious/allegorical elements might have pointed the way to a fresh beginning, or at least a return to the spirit of Superstar and Evita. So what if the obscure Russian novel wasn't especially commercial? For years, Lloyd Webber has said that he harbors a desire to compose a genuine opera, or write a book about Victorian architecture—to get as far away as possible from the megamusical and reconnect with his roots. A musical that featured a suave, disguised Satan arguing with humans about whether either he or Jesus Christ ever existed would bring Lloyd Webber full circle, for redemption has always figured in his works, from Jesus to Evita to Grizabella to the little-engine-that-could in Starlight Express to the Phantom's redemption-by-love at Christine's kiss.

Instead, his next show is likely to be The Phantom in Manhattan, based on Frederick Forsyth's 1999 novel of the same name, which was itself written as a sequel to Lloyd Webber's show, not to Gaston Leroux's source novel. It's already off to a rough start: according to a report in the Daily Mail in June, Lloyd Webber's cat, Otto, managed to jump inside the composer's digital piano and destroy the entire score. (Yes, his cat.)

Still, there's always the bottom drawer; the original Phantom was at first intended to be a pastiche, and was later cobbled together from multiple leftovers. It would be regrettable, but not shocking, were Lloyd Webber to finally succumb to his critics' worst imaginings and, in the end, turn out to be a pastiche artist after all.

Far better, though, were he to rise to the expectation and create something entirely new, fresh and vivid. The Master and Margarita would seem to be a far greater and more exciting challenge than a Phantom rehash. Long freed of financial restraints, he has long had that option, though he hasn't chosen to exercise it.

But surely a show that pits Jesus against the Devil, art against commerce, opera against musical, is where Andrew Lloyd Webber has been heading all his life. Even if he has yet to realize it.

Michael Walsh is the author of Andrew Lloyd Webber: His Life and Works, A Critical Biography (1989).