The Brilliant, Troubled Legacy of Richard Wagner

As the faithful flock to the Bayreuth Festival in his bicentennial year, the spellbinding German composer continues to fascinate, inspire and infuriate

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Richard-Wagner-troubled-legacy-flash-631.jpg)

She is Richard Wagner’s great-granddaughter, and her life has been dominated by the light and shade of his genius. But as a teenager growing up in Bavaria in the 1950s and ’60s, Eva Wagner-Pasquier went googly-eyed for an altogether different musical icon: Elvis Presley. She remembers the excitement he stirred up more than half a century ago merely by passing through a neighboring town on maneuvers with the U.S. Army. So last year, joined by her American-born son Antoine, Eva finally trekked off to Graceland to pay homage to the King. “I’ve always wanted to go there,” she said, flipping open her cellphone to display the idealized image of Elvis she uses as wallpaper. “It was superb! We stayed at the Heartbreak Hotel, of course.”

The trip to Memphis was a lighthearted escape from the burdens of running a family business like no other. Since 2008, when Eva and her half-sister Katharina succeeded their father Wolfgang Wagner, they have directed the famed summer opera festival founded in 1876 by Richard Wagner and managed by his heirs ever since. In this bicentennial year of the composer’s birth, Wagner devotees are now setting forth on their annual pilgrimage to the seat of his still-powerful cultural domain: the charming city of Bayreuth (pronounced BY-royt), nestled far from Germany’s urban centers, in the rolling hills of Upper Franconia. “Wagner without Bayreuth,” observes the cultural historian Frederic Spotts, “would have been like a country without a capital, a religion without a church.”

From July 25 through August 28, the faithful will ascend the city’s famed Green Hill to the orange brick–clad Bayreuth Festival Theater—known globally as the Festspielhaus. It was built by Wagner himself to present his revolutionary works—among them his four-part Ring cycle, Tristan und Isolde and Parsifal—in the innovative architecture and stagings he felt they required. The Bayreuth Festival became the first full-fledged music festival of modern times, the granddaddy of everything from Salzburg and Spoleto to Bonnaroo, Burning Man and the Newport Jazz Festival. At Bayreuth, however, only Wagner’s works are presented. After his death in 1883, the festival and the theater became a hallowed shrine for his followers, many of whom embraced his ideology of fierce German nationalism, racial superiority and anti-Semitism. He was idolized by Adolf Hitler, whose rise was abetted by the Wagner family’s support in the early 1920s.

Through all the cataclysms of modern German history, however, the festival has endured. In the same week Eva Wagner was born in a neighboring village in April 1945, Allied warplanes leveled two-thirds of Bayreuth. Wahnfried—the stately home and gravesite that is the Wagners’ equivalent to Graceland—was 45 percent destroyed in the first of four bombing raids that all somehow spared the Festspielhaus. By 1951, the festival was up and running again under the direction of Wieland Wagner, the composer’s grandson, who had reinvented himself as a post-Nazi opera visionary and rebranded Bayreuth as a haven for avant-garde productions that have periodically offended traditionalists. Yet Wagner loyalists have not wavered, queuing up for a decade and more to attend. This year, for some 58,000 tickets offered for the five-week festival, there were 414,000 applications from 87 countries. The payoff, his admirers feel, is a direct encounter with the sublime. Set aside the associations with the Third Reich, they say, and allow this enthralling music and elemental drama to touch your soul.

If you’ve ever hummed “Here Comes the Bride” (from Wagner’s Lohengrin) or seen Apocalypse Now (the “Ride of the Valkyries” helicopter assault), you have already sipped at the well. Those who have immersed themselves in Wagner’s full operas—lengthy and demanding, yet flowing and churning like a great river of thought and feeling—often experience a sense of awe. “It's so rich and deep—it's like a drug sometimes. If you give up and let go, it really drags you into a mysterious world,” Jonas Kaufmann, the celebrated German tenor, said on NPR in February.“His music is like nobody else’s, emotionally,” says Janet Ciriello, a member of the Wagner Society of Los Angeles who has attended the Bayreuth Festival “six or seven times” since 1985. “It grabs you, and you have to stay with it. Whatever the issue is—greed, or power or Eros—he somehow manages to encompass everybody’s feelings.” Adds her husband Nick Ciriello: “I love Donizetti, Mozart and Verdi, of course, and Puccini. All of these people stir you and grab you, but Wagner picks you up and slams you against the wall. You are in his hands. He’s the grand sorcerer.”

David McVicar, the noted Scottish theater and opera director, believes that potential Wagner fans have been unnecessarily scared off by the perceived difficulty of his works. “I don’t like the idea that any opera composer is approached as a kind of intellectual Everest to be climbed,” says McVicar, who has directed Wagner’s Die Meistersinger and the Ring cycle. “If you have the capacity, if you have the openness of mind, Wagner will talk directly to you. He’ll reach you. He’ll find things inside you.”

By the same token, McVicar says, people tend to find whatever they want in the Wagner cosmos and appropriate it for their own purposes. “Wagner did not create Hitler,” he says. “Hitler found what he was looking for in Wagner. There’s always the dark side and the light side—an inner tension in the works, because it was an inner tension within Wagner himself. I’m interested in the imagination of it. I’m interested in the brilliance of the music, which is on such a high level of inspiration.”

Over time, one’s appreciation intensifies, says Philippe Jordan, the Swiss-born music director of the Paris Opera. “The fascinating thing about Wagner is that it is easily accessible at the very first point—everyone understands the energy of “The Ride of the Valkyries”—but the more you get into his universe, the deeper you can go, and it’s a process which never stops,” Jordan says. “I’m conducting my third Ring cycle [in Paris] now, and I’ve discovered things which I hadn’t been aware of before, although I thought I knew the score very well.”

William Berger, author of Wagner Without Fear and commentator on Sirius XM’s Metropolitan Opera Radio, continually finds more to admire. Most recently, he says, he has been struck by the unity of the operas. “Tristan [und Isolde] is a perfect example,” Berger says, “because the first measure is a famously unresolved chord, and the last measure is the resolution of that chord. And all the five hours in between are getting from A to B.”

***

Born in Leipzig in 1813 and politically exiled to Zurich and Paris for more than a decade following the revolutionary uprisings of 1848–49, Wagner struggled for much of his early career to gain the recognition and rewards he felt were his due. He was quarrelsome, grandiose, manipulative—by many accounts an awful character. “He used women, deceived friends and was constantly groveling for money to pay for his luxurious lifestyle,” Dirk Kurbjuweit writes in Spiegel Online International. Even worse, from Wagner’s perspective, his operas were widely misunderstood and outright scorned by many of his contemporaries. “The Prelude to Tristan und Islode reminds me of the old Italian painting of a martyr whose intestines are slowly unwound from his body on a reel,” the noted critic Eduard Hanslick wrote in 1868. “Wagner is clearly insane,” suggested the composer Hector Berlioz. Taking a gentler approach, the 19th-century American humorist Bill Nye ventured, “Wagner’s music is better than it sounds”—a line frequently misattributed to Mark Twain, a Wagner enthusiast, who enjoyed quoting it.

By the time of his death in Venice in 1883, however, Wagner had become a cultural superstar. Wagner societies cropped up across the globe. He was hailed as the avatar of a new artistic order, the hero of Baudelaire and Rimbaud, “the idol of the impressionists, realists, decadents, postimpressionists, and modernists down to Proust and Thomas Mann,” the historian Jacques Barzun says in the 1958 edition of Darwin, Marx, Wagner.

However powerful to non-Germans, Wagner’s works struck an even deeper chord with his countrymen, especially in the heady days that followed Germany’s unification in 1871. He had become a national symbol, like Shakespeare, Cervantes and Dante. There was an ugly side to Wagner’s conception of nationhood, however: He favored a Germany uncorrupted by Jewish influence, spelling out his views in a notorious pamphlet, Das Judentum in der Musik (Jewry in Music), which helped put wind in the sails of a nascent ultra-nationalist movement that fed on widespread hostility to Jews. “Yet even amid the chorus of nineteenth-century anti-Semitism, Wagner’s rantings stood out for their malicious intensity,” writes the music historian and New Yorker critic Alex Ross, who is writing a book on Wagner.

After his death, the composer’s widow Cosima Wagner (the daughter of Franz Liszt) solidified Bayreuth’s identity as the spiritual center of the movement. Wagner’s son-in-law Houston Stewart Chamberlain became its intellectual leader, much admired by the young Hitler. As the future dictator rose in the 1920s, the Wagner family embraced him publicly. When Hitler was imprisoned following the failed beer-hall putsch of 1923, Winifred Wagner, Richard’s daughter-in-law, brought him the paper on which he wrote Mein Kampf. (She died in 1980, still believing in his greatness.) As chancellor, Hitler became a regular guest at Wahnfried and the Festspielhaus: Bayreuth had become “Hitler’s court theater,” in Thomas Mann’s well-known phrase—a reputation which dogs the festival to this day, as do any vestiges of cultism.

Philippe Jordan admits that he hesitated to go to Bayreuth before he was engaged to conduct Parsifal at the festival last year. “I always was fascinated by Wagner and I always loved him, but I wanted to avoid the ‘German’ Wagner and this kind of pilgrimage which you associate with Wagner and Bayreuth, a kind of fanaticism,” says Jordan, who will conduct the Vienna Symphony Orchestra next season. “Wagner is not just a German composer for me—he’s universal. He was the very first pan-European composer.”

In the end, Bayreuth’s genial atmosphere and idyllic setting were a pleasant surprise, Jordan found, and very conducive to performing. “The people there are not fanatics—they just adore his music.” He adds, “Music, by itself, is not political. Music itself cannot be anti-Semitic. Notes are notes, and music is music.”

***

Needless to say, Germany has changed dramatically since 1945, and today is arguably the best governed and best behaved major power in the world. On the lovely grounds of the Bayreuth Festival Park, just below the opera house, an outdoor exhibition, Verstummte Stimmen (Silenced Voices), individually commemorates the Jewish artists who had been banned from Bayreuth in its darkest period; a number of them were eventually murdered in death camps. The heroic bust of Wagner fashioned by Hitler’s favorite sculptor, Arno Breker, glares at the tall memorial placards. “Germany is the only country that has constructed monuments lamenting its most shameful episode,” Avo Primor, the former Israeli ambassador to Germany, commented in Bayreuth at the opening of the exhibition in July 2012.

The association of Wagner and Nazi Germany remains so firm that his music is not yet performed publicly in Israel. “There is still the feeling, which I respect, that as long as there are Holocaust survivors, we don’t have to force it on them, not in public places,” explains Gabriela Shalev, an Israeli college president and former U.N. ambassador, who attended the Bayreuth Festival a year ago and was greatly moved. “We can listen to it at home, with friends. Most of us go abroad—people who want to hear Wagner can hear him in London, in New York, in Munich.” Shalev’s maternal grandparents were murdered in Auschwitz, but she grew up in a German-speaking home surrounded by German books and culture. Her parents listened to Beethoven and Wagner. “So this is part of the ambivalence that I as a Jew and Israeli bought to Bayreuth,” she says.

The Jewish conductors James Levine and Daniel Barenboim are among the leading interpreters of Wagner in our time, at Bayreuth and elsewhere. Leonard Bernstein was another whose love of the music kept him performing Wagner in spite of profound misgivings. The late New York Philharmonic conductor explored his conflicts in an unreleased 1985 documentary segment filmed, appropriately enough, in Sigmund Freud’s examination room at 19 Berggasse in Vienna. He asked:

“How can so great an artist—so prophetic, so profoundly understanding of the human condition, of human strengths and flaws, so Shakespearean in the simultaneous vastness and specific detail of his perceptions, to say nothing of his mind-boggling musical mastery—how can this first-class genius have been such a third-rate man?”

His answer did not resolve matters.

“I come out with two, and only two clear, unarguable truths,” Bernstein said. “One, that he was a sublime genius of incomparable creative power, and two, that he was a disagreeable, even intolerable megalomaniac. Everything else about Wagner is debatable, or at least, interpretable.”

Endlessly so. In 1924, biographer Ernest Newman apologized for producing four volumes on the composer. “I can only plead in extenuation that the subject of Wagner is inexhaustible,” he wrote. Today thousands of books are listed in the Library of Congress catalog under Wagner’s name. Still more have been published in this bicentennial year, as 22 new and revived Ring productions are being mounted across the world. Yet each generation comes to Wagner anew, starting from scratch, as it were.

One such newcomer is Antoine Wagner-Pasquier, who, like his mother Eva, tends to shorten his name to Wagner for simplicity’s sake.

Born in Evanston, Illinois, raised mainly in Paris and London, Antoine studied theater at Northwestern University and filmmaking at New York University, traveled widely, learned to speak six languages and became a rock video producer and photographer. He has also learned a thing or two from his father, French filmmaker Yves Pasquier. Antoine was slow to come around to the Wagner family’s history, but now, at 30, has made a film with Andy Sommer, Wagner: A Genius in Exile, shown this spring on European TV and released as a DVD on July 1. It retraces Wagner’s journeys through the mountainous Swiss landscapes that influenced the creation of the Ring cycle. A high point, in every sense, was finding the very spot, above the clouds, where Wagner said he was inspired to write “The Ride of the Valkyrie.” “I felt like I'd been walking through his sets,” Antoine says.

With his background, could he see himself taking on a role at Bayreuth someday?

“I’m slowly going towards that,” he says. “In the near future, I have other plans, other desires. But it’s true that if it presents itself one day, it’s not something that I’ll just kick out of the process, but something that of course I’ll consider.”

That may or may not be music to the ears of his mother, Eva,

She grew up in Bayreuth back when her uncle Wieland and father Wolfgang directed the festival. She lived on the grounds of Wahnfried for many years. She remembers climbing around in the rafters of the Festpielhaus as a young girl, scaring the wits out of the watchman on duty. But her family life had all the Sturm und Drang of the Ring cycle. There was a long estrangement from her father after his second marriage, and always a good deal of controversy, family feuding and gossip—artistic, financial, political. It comes with the territory. The Wagners are the royal family of German culture, with all the public scrutiny that entails.

The result has been to focus all of Eva’s energy on the thing she cares about most, which is the survival of the Bayreuth Festival as a living and ever-evolving cultural enterprise refreshed by new productions of her great-grandfather’s works. It is an enormous, year-long effort involving hundreds of artists and craftspeople in a remote location, all for a short, five-week series of world-class opera performances.

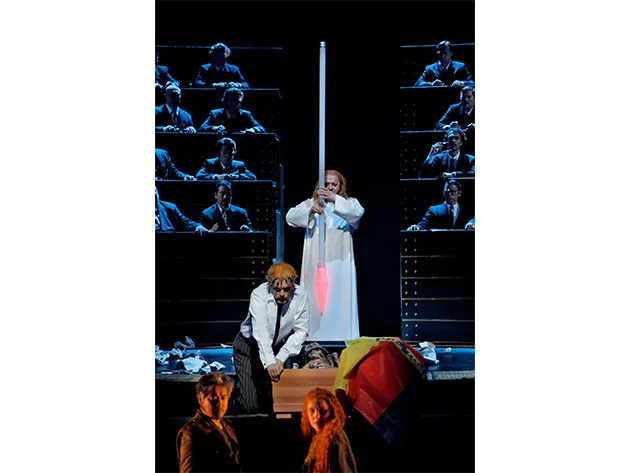

“It starts when you have a little model,” of the proposed stage set, she said several months before the opening of this summer’s much-anticipated new Ring production by Frank Castorf. “And then the designer comes in, and the director, and now, suddenly, last week, this little model was already on stage for Das Rheingold. It’s like a miracle, like a birth—something absolutely outstanding.”

And then, on opening night, the first extended note of the Ring will emerge from the silence of the Festspielhaus orchestra pit, and the drama will begin anew.

Leonard Bernstein quotes are courtesy of The Leonard Bernstein Office, Inc.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jamie-Katz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jamie-Katz-240.jpg)