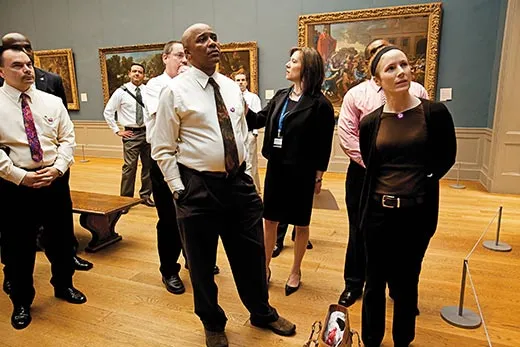

Teaching Cops to See

At New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, Amy Herman schools police in the fine art of deductive observation

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Amy-Herman-teaching-police-officers-631.jpg)

Early one morning a bunch of New York City police officers, guns concealed, trooped into the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Inside a conference room, Amy Herman, a tall 43-year-old art historian and lawyer, apologized that she hadn't been able to provide the customary stimulant. "I usually try to give you coffee with plenty of sugar to make you talk more," she said.

The officers, all captains or higher in rank, were attending "The Art of Perception," a course designed to fine-tune their attention to visual details, some of which might prove critical in solving or preventing a crime. Herman laid out the ground rules. "First, there are two words that are not allowed—'obviously' and 'clearly'—since what's obvious to you may not be obvious to someone else. Second, no reading of labels. For purposes of this exercise, we are not focusing on who the artist was, the title of the work or even when it was created. Third, I want hands back, no pointing. If you want to communicate something, you have to say, 'Up in the left-hand corner, you can see...' "

Herman did not want to talk about brush strokes, palettes, texture, light, shadow or depth. Schools of painting and historical context were moot. Suspecting that some of the cops were first-timers to the Met, she tried to ease the pressure. "Remember," she said, "there are no judgments and no wrong answers."

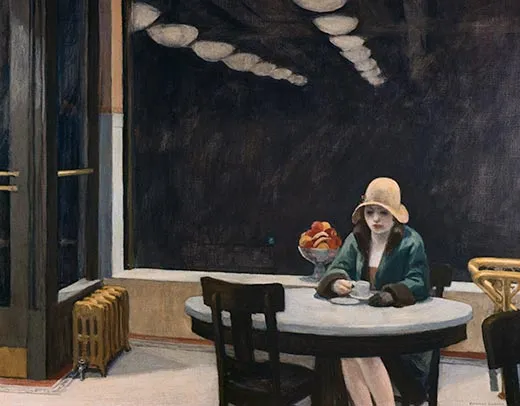

She showed slides of paintings by James Tissot and Georges de La Tour. There was an Edward Hopper in which a hatted, forlorn-looking woman sits alone at a table, sipping from a cup.

"OK, what do we see here?" she said.

"A woman having a cup of coffee," answered one of the cops.

"Unlike us," another said.

Herman said, "Do we know it's coffee?"

"If it was tea, there would be a spoon."

"Or a pot, like in England."

A Caravaggio appeared on the screen. In it, five men in 17th-century dress are seated around a table. Two others stand nearby, and one of them, barely discernible in shadow, points a finger—accusingly?—at a young man at the table with some coins.

Among the officers a discussion arose about who robbed whom, but they soon learned there could be no verdict. No one was being accused or arrested, Herman said. The painting was The Calling of St. Matthew, and the man in the shadow was Jesus Christ. The cops fell silent.

Later, Deputy Inspector Donna Allen said, "I can see where this would be useful in sizing up the big picture."

Herman led the students upstairs into a gallery. The cops split into two- and three-person surveillance teams, each assigned to a particular artwork.

One team huddled in front of an enormous painting in which a heavily muscled man with close-cropped hair was being manhandled by a throng of armored ruffians and a buxom woman who was tearing off his shirt.

Robert Thursland, a 52-year-old inspector who looked trim and corporate in his gray suit, gave the class the skinny. The painting appeared to depict the end of a trial, and the muscle-bound fellow was "possibly being led off to be tortured," said Thursland. The woman tugging at his clothes was part of the lynch mob, he added.

Herman revealed that the officers had been scrutinizing a 17th-century Guercino painting of Samson after his capture by the Philistines—the woman, of course, was Samson's lover and betrayer, Delilah. That corroborated suspicions in the room as to victims and perps, and everyone seemed to agree the case could be closed.

In another gallery, a squat Congolese power idol, embedded with nails and gouged with holes and gaping gashes, appeared to be howling in pain. "When you came through these doors," Herman said, "what struck you about him?"

Assistant Chief George Anderson, who commands the Police Academy, said with a sigh, "First thing I thought, 'Boy, this guy caught a lotta flak. I kinda felt it was me.'"

Back in the conference room, Herman had the group pair up and take seats. One person faced forward while the other sat with his or her back to the screen. The officers who could see the pictures described them to their partners. One slide showed the well-known 1970 photograph of a teenage girl at Kent State kneeling beside a student who has been shot by the National Guard.

Anderson told his backward-facing partner: "The woman is obviously distraught."

Ms. Herman scolded, "Uh-oh, I heard an 'obvious' out there!"

"Oops!" he said. "That's the second time I did that."

Another photograph showed two couples standing side by side. Herman cautioned that neither should be identified by name, only by body language. The consensus was that the younger couple looked happy, playful and brimming with enthusiasm, while the older couple seemed stiff, worried and ill at ease.

Eyeballing the older couple, Thursland offered, "They don't know where they're gonna be living come January. "

They were George and Laura Bush; the younger couple, Barack and Michelle Obama.

Herman, who grew up in Somerset, New Jersey, and earned a master's degree in art history as well as a law degree, began her career as an attorney in a private firm. But after a while her lifelong love of art held sway, and she went on to manage programs at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, assist the director of the Frick Collection in Manhattan and give lectures on 19th-century American and French paintings at the Met (which she still does). She's currently the director of educational development for the New York City public television station WNET. She began teaching her three-hour "Art of Perception" course at the Frick in 2004, to medical students at first. Then, over pizza one night with a friend who wondered why Herman limited her students to future physicians, Herman recalled a harrowing experience she had had while studying law at George Washington University.

Assigned by a professor to accompany police on patrol runs, she had raced with two cops to the scene of a raucous domestic dispute. Standing on the landing below, Herman watched one officer bang on an apartment door while the other nervously fingered his handgun. What the first officer saw when the door opened—a whining child, say, or a shotgun-toting madman—and how he communicated that information to his partner could have life-or-death consequences, she realized.

The following Monday, Herman made a cold call to the New York City Police Academy to pitch her course. And four months later, she was teaching NYPD captains at the Frick. One comment she remembers was an officer's take on Claude Lorrain's 17th-century painting Sermon on the Mount, in which a crowd gazes up at Jesus. "If I drove up on the scene and saw all these people looking up," the cop said, "I'd figure I had a jumper."

Herman, speaking to the class I attended, underscored the need for precision by recounting the murder of a woman whose body was not found for more than a year, partly, according to news reports, because of a commander's vague instructions about where to look for it.

Anderson, who is often called to crime scenes, took the lesson seriously. Instead of ordering detectives generally to "search the block" for shell casings, weapons or other evidence, he said he would now tell them specifically to start at the far end, work their way back to the near end, look under all the parked cars, behind the gated areas, in the shrubbery, in the garages and in the trash cans.

One of Herman's graduates, Lt. Dan Hollywood, whose last name seems well-suited to his Jimmy Stewart-like demeanor, said her pointers have helped snag pickpockets, handbag snatchers and shoplifters who prowl the Times Square area. Hollywood coordinates the Grand Larceny Task Force of 24 plainclothes officers. "Instead of telling my people that the guy who keeps looking into one parked car after another is dressed in black," he explained, "I might say he's wearing a black wool hat, a black leather coat with black fur trim, a black hoodie sweatshirt and Timberlands."

New York's finest aren't the only law-enforcement types to benefit from Herman's teaching. Other students have included U.S. Secret Service agents and members of the Department of Homeland Security, the Transportation Security Administration, the Strategic Studies Group of the Naval War College, the National Guard and, during a visit to London, the Metropolitan Police of Scotland Yard.

Perhaps the most vivid illustration of art's crime-fighting power involved a task force of federal, state and local officers investigating mob control of garbage collection in Connecticut. One FBI agent went undercover for 18 months, and during that time, as it happened, attended one of Herman's classes at the Frick. According to Bill Reiner, the FBI special agent who heads the task force, Herman's exercises helped the undercover agent sharpen his observations of office layouts, storage lockers, desks and file cabinets containing incriminating evidence. The information he provided led to detailed search warrants and ultimately resulted in 34 convictions and government seizure and sale of 26 trash-hauling companies worth $60 million to $100 million.

"Amy taught us that to be successful, you have to think outside the box," said Reiner. "Don't just look at a picture and see a picture. See what's happening."

Herman has taken her lessons to heart. When her 7-year-old son, Ian, was in preschool, his teacher worried that he wasn't verbal enough and suggested that Herman try some of her exercises on the boy. Herman pressed him to describe in detail what he saw when they were at home or on the street. "It worked!" Herman says. "We started talking about all the things we see and why we think they look that way, and he hasn't stopped talking since."

She encounters frequent reminders of her pedagogy's impact. While riding the subway not long ago, Herman noticed two burly men giving her the eye. They were unshaven and dressed in shabby attire. They made her nervous, and she got ready to get off the train at the next station.

Then one of the men tapped her on the elbow. "Hey," he said, "we took your course. We're cops."

Neal Hirschfeld's latest book, Dancing With the Devil, the true story of a federal undercover agent, will be published next year. Photographer Amy Toensing is based in New York City.