Spoken Like a Native

Learning a minority language opens doors—and hearts

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/last-page-learning-minority-language-631.jpg)

The reasons for learning languages are numerous—if not always obvious. Standing in a lost luggage line recently at the Falcone-Borsellino Airport in Sicily, I watched as a group of new arrivals tried to cut ahead of me by forming a second line at one of the other windows. “La queue est ici,” I said sharply, and, throwing me nasty looks, they reluctantly moved behind me. Why be an ugly American when you can be an ugly Frenchman?

Marquee languages definitely serve their purposes. But when you learn a minority language, like Romansh or Sioux, you become a member of a select group—a linguistically exclusive club. And with membership comes privileges.

Like secrecy. My wife is from Poland—where I lived for two and a half years—and though we rarely use her language at home, we find it comes in handy at a boring party or a bad art show. (We’re more careful, of course, when we visit Chicago, which has more Poles than any city outside of Poland.)

But the real beauty of speaking a minority language is the instant acceptance you get from native speakers. (An illustration of this is the 1997 book Travels in an Old Tongue by Pamela Petro, who learned Welsh and then visited Welsh-speaking communities in, among other places, Norway, Singapore, Japan and Argentina.) By learning a language that is usually considered difficult and not markedly practical, you accomplish something few outsiders attempt. And appreciation for your effort is almost always greater than that shown, say, to a French major spending her junior year in Paris.

Yet the benefits extend beyond appreciation. When you acquire a new language, you acquire a new set of references, catchphrases, punch lines, songs—all the things that enable you to connect with the people. And the smaller the community, the deeper the connection. Speakers of D-list languages often feel misunderstood; a foreigner who understands—gets the allusions, reads the poets—not surprisingly becomes like family. All languages open doors; minority languages also open hearts.

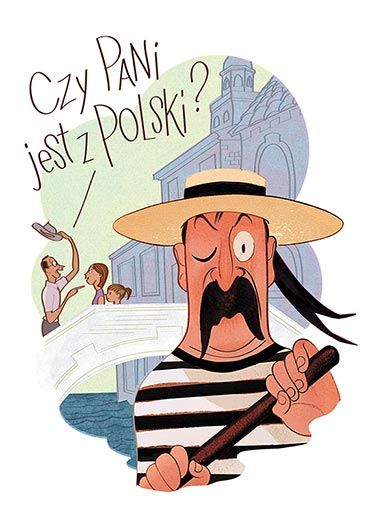

I rarely stop when I hear people speaking French; I almost always butt in when I hear the susurrations of Polish. In Venice recently, wandering around the district of Dorsoduro, I overheard a conversation between a mother and her young daughter. I asked the woman if she was from Poland—“Czy Pani jest z Polski?”—an unnecessary but grammatically correct question (no small feat in a highly inflected tongue). She was from Lodz, she said, but was now living in Venice. We continued chatting as we crossed a bridge. Along with the common language was the shared experience of living in Poland; the fact that her husband, a painter, was American; and the mutual, unuttered realization that it was just as unusual for her to meet a Polish-speaking American on a stroll through the neighborhood as it was delightful for me to meet a Polish resident of Venice. She invited me to dinner.

Thomas Swick wrote about Japan’s Kiso Road in the October 2010 issue of Smithsonian.