Spirals of History

Hand-carved elephant tusks tell the story of life in the Congolese colonies of the late 1800s

In 1882, Robert Visser, a German merchant who had been offered an opportunity to manage cacao and coffee plantations, traveled to central Africa's Loango Coast (in present-day Congo Republic). From then until his departure 22 years later, Visser avidly collected African art. His notable acquisitions included three outstanding examples of the region's intricately carved elephant tusks—artifacts newly added to the Smithsonian's National Museum of African Art. (Two of the ivories go on view this month in the exhibition "Treasures 2008," a sampling of works from the museum, supplemented by objects on loan.)

During his sojourn abroad, Visser, who was largely self-educated, took up photography and pursued it with dedication at a time when using an unwieldy camera under difficult conditions (in places where, for instance, one might become a lion's lunch) required as much toil as technique. While in Africa, Visser made some 500 photographs.

Visser's dual preoccupations—art collecting and photography—converge in the iconography of the tusks, which range in height from two to three feet and were acquired late last year from a Swiss collector. One of the pieces features a man standing by a big box camera (see Table of Contents, p. 4). Immediately, says curator Christine Mullen Kreamer, "we knew we had something unique."

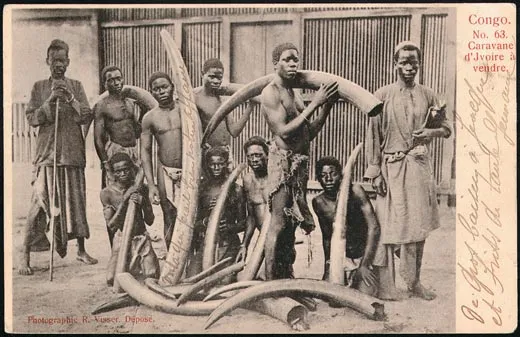

The figure, almost certainly Visser himself, presides over a large-view camera mounted on a tripod. Each of the Visser ivories, moreover, features scenes that echo pictures made by Visser—a couple seated in a thatched-roof hut; African hunters displaying elephant tusks. One of the tusks contains a telling inscription at its base: "Mit Muth nur Kraft R Visser"—Only With Courage Is There Strength, R Visser.

The master artisans who created these pieces, says Kreamer, included various coastal peoples of the region, well-versed in a "long tradition of carving, mainly in wood." Among them were the Vili, who traditionally hunted elephants (the meat was a dietary staple). After the Portuguese arrived in the region toward the end of the 1400s, ivory tusks began to be exported, eventually for use in products such as piano keys and billiard balls. For travelers, missionaries and foreign workers in the rubber and cacao trades, elephant tusks became souvenirs of choice.

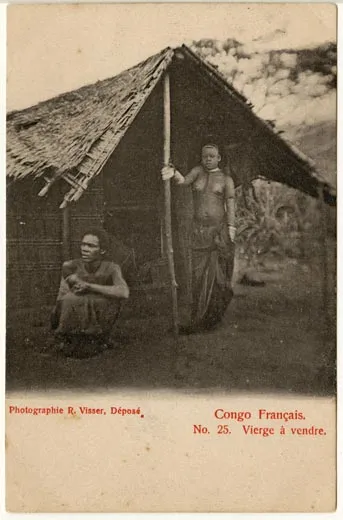

"Ivories had been a symbol of prestige among the Vili, who were the primo elephant hunters in that part of the continent," says Kreamer. "But tribal tusks weren't necessarily elaborately carved." Beginning in the 1830s, finely worked tusks, often commissioned by foreigners, began to appear. These, Kreamer adds, tended "to depict genre scenes in a highly naturalistic way—local trades, workers, scenes of struggle, animals, ritual activities. Often there would be a commissioned inscription as well, such as ‘Memories of Savage Africa.'"

Ultimately, of course, the appetite for ivory spelled doom for Africa's elephant herds. In an attempt to curb the slaughter, an international ban on the sale of new ivory was imposed in 1989. (The ban does not apply to antique ivory objects.) At first, the restrictions proved largely successful. Today, however, a worldwide market for new ivory trinkets, readily available on the Internet, has surged. Estimates from the Center for Conservation Biology at the University of Washington suggest that in 2006 alone, poachers smuggled 240 tons of ivory out of Africa, an amount corresponding to the destruction of 24,000 elephants.

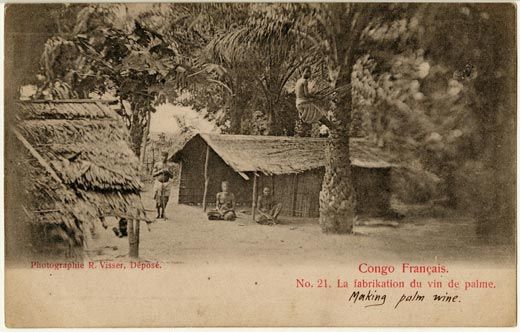

Visser's 19th-century tusks document a vanished world and reveal, says Kreamer, a wealth of information about the flora, fauna and clothing of the time. The pieces also offer a sense of the complex interactions among Africans and Europeans—including the more brutal aspects, such as chaining workers together in forced labor. Each tusk bears a distinctive carved band, twining from base to tip and connecting scenes and characters. This defining motif caused Kreamer and her colleagues to create the term now used to describe Loango ivories in general (and this trio in particular): "spirals of history."

Owen Edwards is a freelance writer and author of the book Elegant Solutions.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)