This Sculpture Is Controlled by Live Honeybees

Artist Wolfgang Buttress collaborated with a multidisciplinary team to create a giant, metallic hive

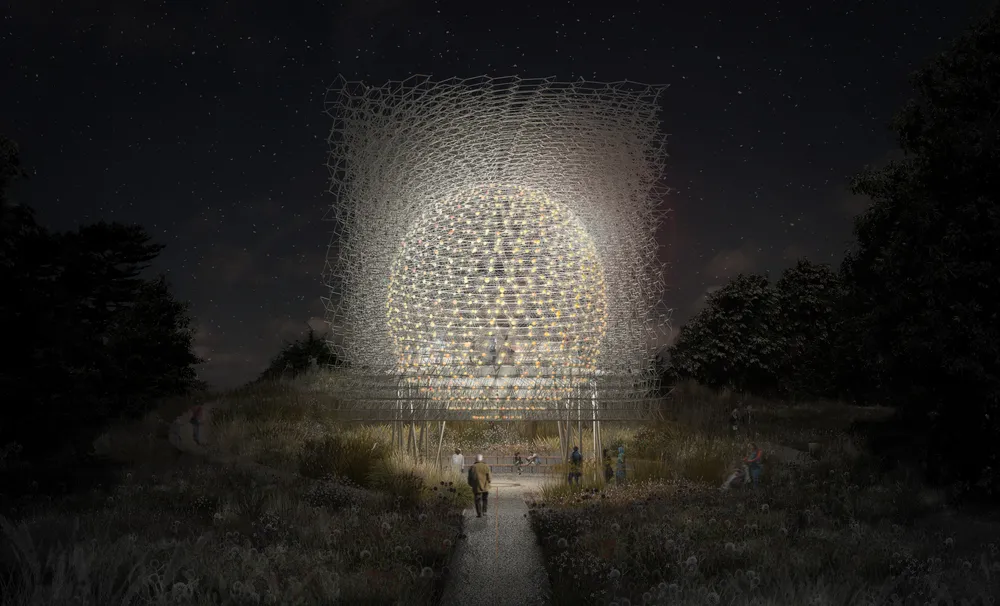

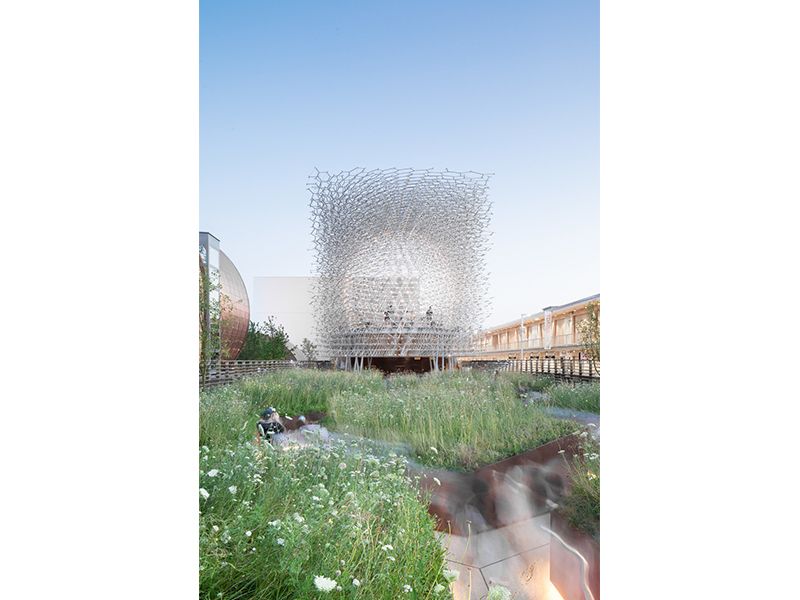

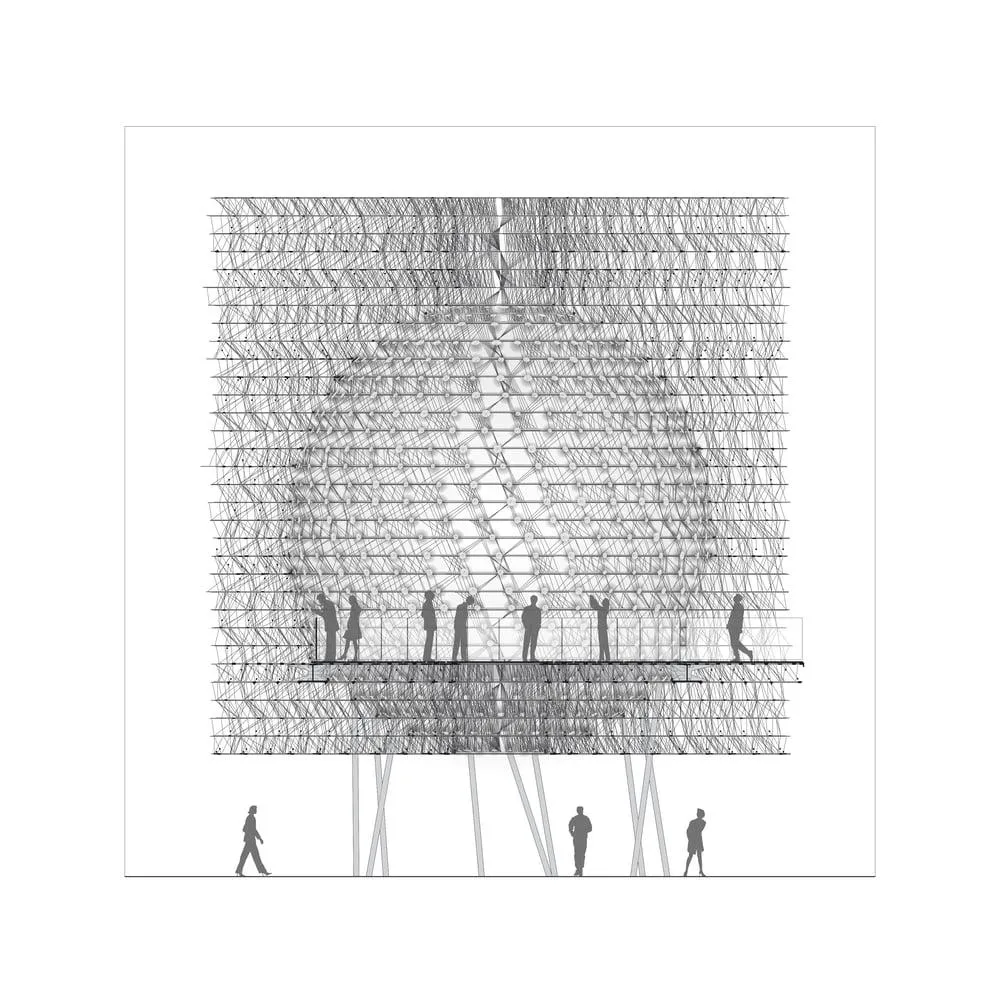

To reach artist Wolfgang Buttress's new sculpture, one must first walk through a field of wildflowers. From a distance, the installation seems to float above swaying blooms, like a gossamer cloud or a swarm of gnats. As the viewer approaches, however, the structure resolves into a honeycomb lattice of aluminum bars and rods that spiral slightly as they rise up 56 feet in height. Another few steps reveal people moving through the huge metallic hive.

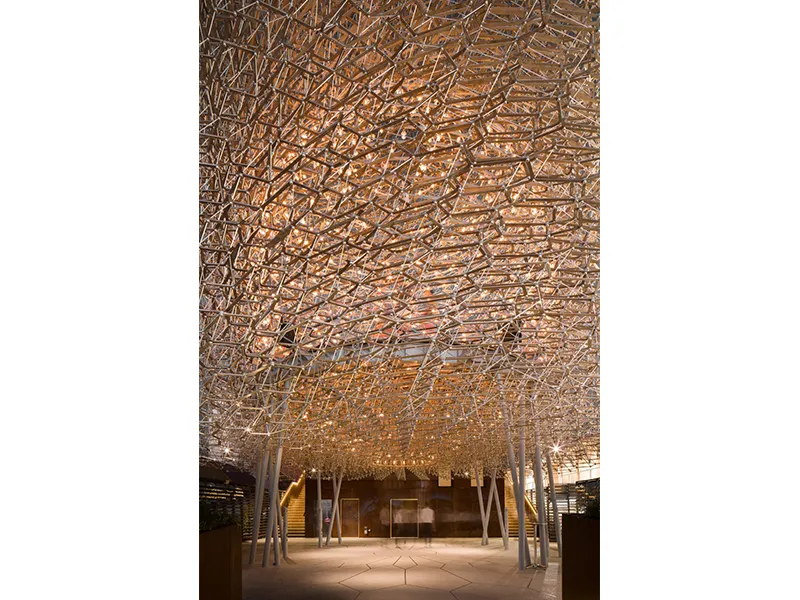

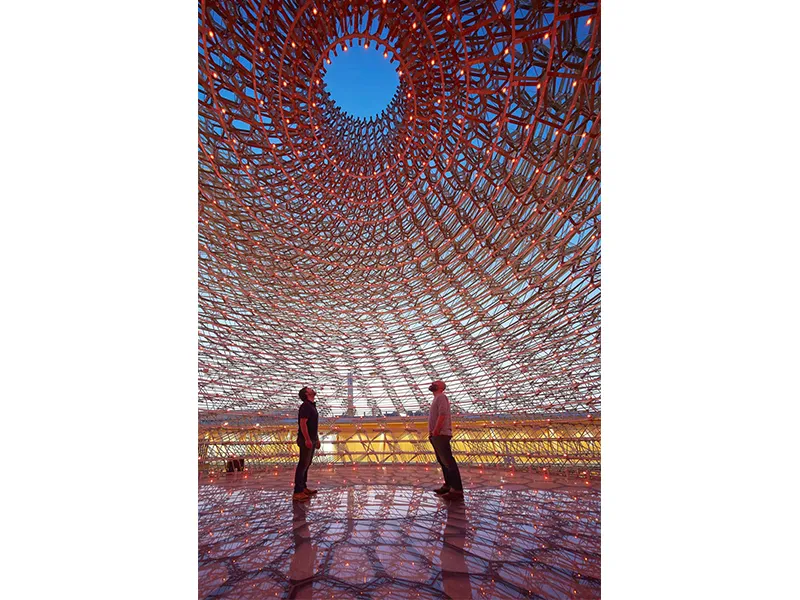

Thoughts of bees and swarms are exactly what the structure should provoke. "The Hive" is all about pollinators and their importance. Inside the sculpture, about 1,000 LEDS flicker in response to the activity of a nearby beehive and an amplified buzz of the insects mingles with a soundscape of violins, cellos, voices and other instruments.

"I was really keen to create an immersive experience, so it wouldn't just be something to go and look at but something you can feel," Buttress says.

With a team of artists from his studio, landscape architects, a scientist and musicians, Buttress created "The Hive" for an international audience at the 2015 World Expo in Milan, Italy. Now, the sculpture is enjoying a second life at the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, in London, England.

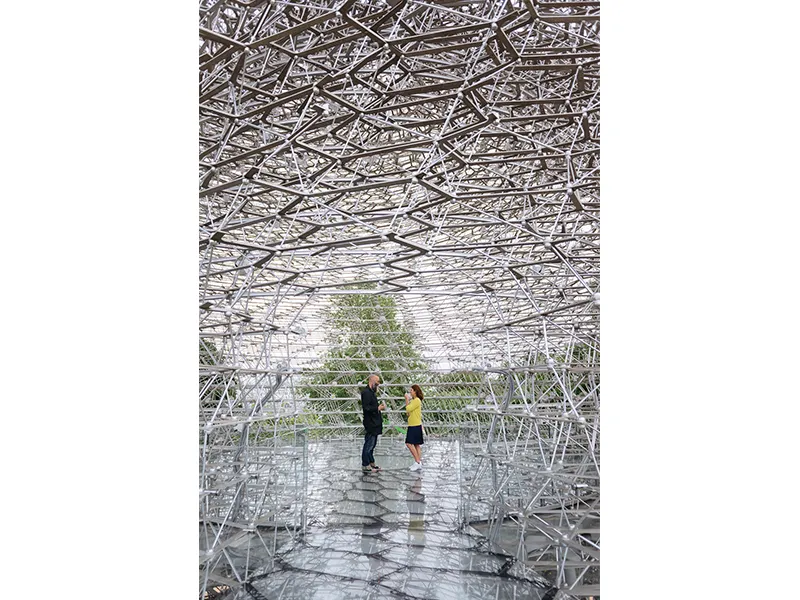

"The Hive” is made from approximately 170,000 pieces of aluminum, which weigh a total of some 44 tons. Buttress used water jets to cut each piece, so that they fit precisely into the work of art. While not a replica of real hives, the structure does echo the repetition of a honeycomb, a structure that Buttress calls “a wonderful example of the perfect harmony between form and function.” He also designed the sculpture to be assembled on site, making it possible to move from the World Expo to the gardens.

Visitors enter “The Hive” from underneath, looking up through the center glass oculus to see people walking above and the sky beyond. They go outside again before plunging into the heart of the sculpture. Inside, the honeycomb is obvious.

"In a way, it is a very calm, meditative space," says Buttress. "The thousands of pieces of metal have a repetition and delicacy. It changes as the light and weather conditions change—the pieces sparkle or are more gray. It kind of transports you."

When organizers of the 2015 World Expo chose the theme "Feeding the Planet: Energy for Life," Buttress, a Nottingham, England-based artist, knew that he wanted to create something that spoke to that theme in a very simple but engaging way. He thought of bees.

About a third of the annual agricultural output in the United States relies on pollinators. While bees are not the only pollinators to help plants reproduce, honeybees are incredibly important for about 100 species worldwide that humans enjoy. Commercially-run hives help pollinate many seasonal goodies, such as blueberries, peaches, almonds and apples.

Buttress frequently creates works that share sensibilities with architecture and demand that viewers consider their place in nature. "It is maybe helpful to be a little humble," he says. "We are not this all-powerful species, and bees are incredibly important to us."

Plus, there's something that seems to fascinate people about bees. It might be their role in producing sweet and sticky honey, or their intricate social organization and intelligence. Buttress has long been intrigued by how animals and nature build structures, but as he learned more about bees he grew to appreciate their skills and quirks.

For about a decade, people worried about the fate of bees. In 2006, beekeepers in the U.S. reported losses of more than a third of their hives on average. In Europe and the U.K., beekeepers have also struggled. Since then, scientists have been searching for the causes.

As far as experts can tell, a host of problems are plaguing the honeybee: climate change, parasitic mites, viral infections, loss of undeveloped land and possibly pesticides.

To Buttress, bees are "barometers for the health of the Earth," he says. "The healthier the bee, the healthier the hive and the healthier the planet. Maybe the reverse is also true."

With the importance of bees in mind, Buttress pulled together a team with a diverse set of talents to create "The Hive." He met with Martin Bencsik, a researcher at Nottingham Trent University who had outfitted a colony with tens of thousands of honeybees with an accelerometer, to measure their vibrational messages and to better understand and try to predict when they swarm. In a way, Bencsik’s research has become something that others can now experience through Buttress’s art.

Once Buttress understood how the devices work, they rigged a nearby hive with the accelerometers. These accelerometers record the sounds and vibrations created by wing buzzes and bees’ crawling through the hive or messaging each other with pulses. The recordings are then fed into the programming that controls the sounds and lights of the sculpture.

For the Kew installation, the sculpture’s lights and sound are wirelessly connected to the bees in the hive. When the accelerometer-outfitted bees are quiet and drowsy in the morning, the lights in the sculpture flicker gently. In the afternoon, when activity picks up, so does the sculpture. "On a day where it is sunny, the lights are really flashing like crazy," Buttress says. Hives are typically most active on sunny, pleasantly warm days.

The music in the soundscape also takes its cues from the bees. Buttress approached a group of musicians he knew, and they composed the sculpture’s soundtrack. First, they streamed the sound of a humming hive into their Nottingham studio. Amplified, the sound of a beehive can be intense. But cellist Deirdre Bencsik (who is married to Martin) immediately realized that bees hum in the key of C. She joined in.

"We had this incredible, sonorous, visceral sound of the cello with the bees," Buttress recalls. "Then Camille [Buttress], who is a singer, she just started singing from the top of her head this sort of automatic poetry. And we had this beautiful triangle of the bees, the cello and the human voice." Camille is the artist's daughter.

The group jammed with the bees for hours, and the soundscape they wove became the basis for the one used in the installation. While the music is prerecorded, the system is programmed so that when the bees’ activity changes or the frequency of their hum modulates, specific melodies and themes will play in response. "At certain times of the day, certain pitches from the bees will trigger off the violin or the piano or the guitar," Buttress says.

The musicians, now known as “Be,” made an album, called "One," probably the only collaboration between humans and 40,000 bees to ever hit the charts. "We had a joke in the studio that they were the best band members we’ve ever had," percussionist and pianist Kev Bales told Tim Jonze of The Guardian. The bees and musicians also harmonized in several live performances over the past year.

"It means that we can get the idea of the importance of bees to a whole new audience," Buttress says.

Making “The Hive” was a truly collaborative, interdisciplinary effort.

"You could imagine with this type of project that there'd be all these battles and arguments, but I think there was a real sense of letting go because the subject is so strong," he says. "It was all about the bees."

"The Hive" installation at Kew will run through the end of 2017. Entry is included in admission to the gardens. Images and information on other work from Wolfgang Buttress as well as the album "Be: One" can be found on his studio's website. “Be” will play live at “The Hive” on September 28 and 29.