Q and A With William G. Allman

The curator of the White House talks about the history of the President’s mansion and how to protect the collections from tipsy visitors

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/QA-William-Allman-White-House-631.jpg)

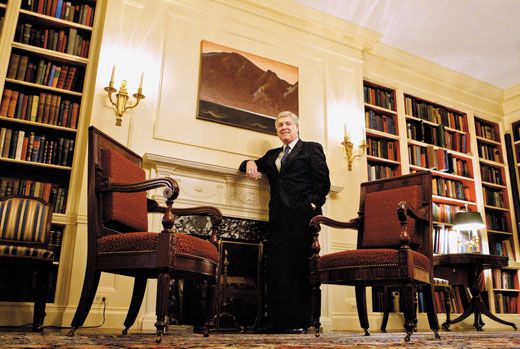

As curator of the White House, William G. Allman is responsible for studying and caring for the 50,000 pieces of art and décor in the residence’s permanent collection. Something of Splendor: Decorative Arts from the White House, an exhibition featuring 95 of the items, opened this October at the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Renwick Gallery. Allman spoke with the magazine’s Megan Gambino.

In 1961, Jacqueline Kennedy became the first to recognize the White House as a museum. But it’s also a home to a family. Do you ever have the urge to say, “Don’t touch that!”

Oh, definitely. That is the dynamism of this house, of this concept. It is, principally, a home and office. The fact that it is a museum is an extra layer of interest to the house that isn’t really part of its long-term and necessary existence. So clearly there are those moments when curators are ready to pull out their hair and say, please don’t touch. But there are activities that require people to touch and sit and walk on and eat off of. Then, in order to set up for events, people have to handle things sometimes on a moment’s notice and our operations crew, in whom we put great faith, may have to pick up things in a hurry. Where you would like them to have two guys on a piece, one may have to grab it. And when you’d like them to not touch the fabrics, they may have to touch them. It’s complex.

Since the White House is a home as well as a museum, does that present unique challenges for the curators?

There are people at parties who are careless at times, spilling wine on the upholstery of a chair. One year someone managed to throw a glass of eggnog on the Green Room wall. Mostly, the public tours aren’t a problem, since they are confined to careful paths. The pets have never created any serious trouble. Although, occasionally, there is that moment when the first lady admits, “OK, the puppy peed on the Oriental rug.” In most cases, that’s when they say, “Why don’t we remove the rug for safekeeping until the dog is better behaved?”

All the White House’s decorative objects have a story to tell. Which is your favorite?

In the area of fine arts, the portrait of George Washington that hangs in the East Room has the most compelling story about being the first art object on the wall when the house opened in 1800 and being designated by First Lady Dolley Madison as something that was essential to save before the British burnt the White House. It is kind of our great icon. It is the one thing that has the longest history of use in the house. President James Monroe purchased two gilt bronze mantel clocks from France in 1817. They were figural clocks. One of them was the Roman goddess Minerva, an iconic symbol of wisdom. But the other clock seemed a more random choice—Hannibal, the Carthaginian general. The agents who were charged with buying the clocks wrote to President Monroe that they were having trouble finding classical figures who weren’t nude. So I think they may have picked Hannibal not because of his symbolic importance, but because he was wearing all of his clothes.

What do you love most about your job?

The house is so alive, because you have a new administration every four to eight years. We are commemorating the lives of an unending sequence of people that are “the presidency.” So I think that the fact that it is a household collection, it doesn’t have just a narrow focus. It isn’t just a fine arts museum, or it isn’t just a history museum. But that it is a little bit of everything. We have a small staff and everybody has to be reasonably well versed in many things. Though there is an assistant curator for the fine arts, she obviously knows something about the furnishing collection and other memorabilia that we have and photographs and the history of the house and the uses of the rooms. Everybody on the staff is required to have that same sort of broad understanding, so none of us are specialists. In a really big museum, you might have somebody who is truly a specialist in 16th century French armor or something. But I think we have more fun being generalists here, which is probably true of house museum people all over the country.

Decorative choices can sometime seem political. What, in your experience, has been one of the most controversial pieces?

Well, probably the most controversial time was early in the Lincoln administration, just because the country was in an upheaval with the outbreak of the Civil War, and Mrs. Lincoln wanted the White House to look good for her purposes and her husband’s purposes even if it was a trying time. And, so, she was fairly noted for having spent the budget and then spent some more. It made awkward times for the president, who was quoted as saying something to the effect of, how do I justify buying flubdubs for the White House when the troops don’t have blankets? Mrs. Lincoln was still seeing the White House as requiring a certain elegance. I don’t think she was completely wrong, but I think she did make it a little hard for the president.

What is the most curious object in the collection?

One would be a chair that was carved out of a single log. It was sent to President Herbert Hoover in 1932, presumably to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the birth of George Washington. And it is surprisingly comfortable. It had been in storage for years and years until first lady Laura Bush asked us to put it in the solarium on the third floor. When you walk into the room and see that chair for the first time your immediate thought is, “What the heck is that?”

What administration has left the biggest stamp on the collection?

It is a little hard to say. Mrs. Kennedy obviously gets enormous credit for starting the museum focus, the Curator’s Office, and the White House Historical Association, and she received enormous public credit when she did her televised walk through the house and emphasized the idea that we are trying to preserve, and we’re trying to interpret, and we want people to visit. I think that changed the White House in many ways. Other than just increasing the collection, it also added to the idea that the house was an even more important destination for the public to come to get a chance to go in and see beautiful things.

In a somewhat equal vein, in 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt and his wife Edith wanted the high style Victorian décor of the 19th century to be removed in favor of a house that was more classically decorated like its exterior. So what Mrs. Kennedy found in 1961 was a house that for nearly 60 years had stayed very calm and level because the architecture had stayed the same, the furnishings had largely stayed the same. It was kind of a stage set more than a growing and actively redecorated house as it had been in the 19th century. In some respects, the 1902 renovation put the White House on the map as a historic set.

And Mrs. Kennedy simply boosted its significance a lot by saying, well, if it’s going to be an historical set, let’s make it an historical set of real things, genuine antiques and wonderful, American paintings and furniture, rather than just 1902 simulations of what a good early 19th century American presidential home should look like.

The exhibition includes some murals and photographs that show the objects. Lots of pieces once in the White House were auctioned off, and several have been reclaimed. What is at the top of your wish list, in terms of items you know existed based on murals and photographs?

In some cases we have been lucky because the White House would buy multiples of things. You would need four matched tables or 24 matched chairs. Once you get one or two back, you could always say you would like some more, even if you are not totally missing what it looked like or what it represents. One of the things that is among the most tragic, was in 1882, when Chester Arthur was the president. He was good friends with Louis Comfort Tiffany, who, in redecorating the public rooms, installed between the columns in the entrance hall 350 square feet of Tiffany stained glass, a giant screen made in red, white and blue glass. Tiffany lamps and Tiffany stained glass windows are highly prized and are considered great monuments to American design. The screen was taken down in 1902 when Theodore Roosevelt renovated the White House and was sold at auction. It went to a man who owned a hotel on the Chesapeake Bay. The building burned down in 1922, and as far as we know, the screen was melted into oblivion. It exists in some black and white photographs and it exists in some color, hypothetical recreations. It would be fun if somehow somebody was able to suddenly show up one day and say, you know, my great grandfather rummaged through the remnants of the hotel and pulled out these chunks of the Tiffany stained glass screen. It would be pretty great to have those back, even if only as a documentary object, since we wouldn’t want to re-establish it. Even if the entire screen existed, it wouldn’t fit the décor any longer.

In your career in the White House curator’s office, is there a moment when you really felt like you had a privileged view of life in the White House?

In the year 2000, we celebrated the 200th anniversary of the opening of the White House. They had a big gala dinner in the East Room, where they invited all the former presidents and first ladies. The head table was everyone but the Reagans, because President Reagan was already in poor health. But it was President and Mrs. Clinton and former president and Mrs. George H. W. Bush, Mrs. Johnson and the Carters and the Fords. Since the folks in our office are interested in history, we were invited to participate in the dinner and say hello to former presidents with whom we had worked. Basically, everybody I had worked with. President Carter got up. President Ford got up. In each case, they talked about how important the house was to them, what it looked like, what was in it, how it helped make their jobs easier, how wonderful the staff was in taking care of them and taking care of the house. It was just one of those moments.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)