Q and A: James Luna

The Native American artist talks about his “Take a Picture With a Real Indian” performance

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/QA-James-Luna-631.jpg)

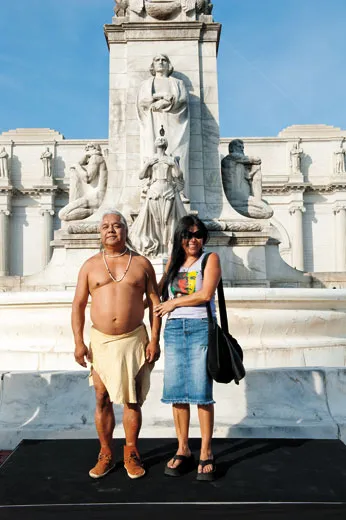

Performance artist James Luna, a member of California’s Luiseño tribe, likes to blur the boundaries of his Native American culture. This past Columbus Day, he stood in front of Washington, D.C.’s Union Station and invited passersby to take his picture. He spoke with the magazine’s Jess Righthand.

What inspired the Union Station piece?

While traveling in the Southwest, I spent some time in a very remote area of the Navajo reservation. Off the highway, there was an Indian in war dance regalia, next to this thrown-together jewelry stand. But if you knew anything about that particular Indian culture, you would know that garb isn’t their tribal outfit. It was somewhat demeaning, even though he was making a living. Later on that year I was in D.C., and there were life-size cutouts of the president that you could take your picture with in front of the White House, and I thought, “Wow, that’s pretty cool.” I didn’t take a picture, and I’m sorry I didn’t. Later on I got invited to do a show in New York about tourism, and so those two incidents I put together.

So how did it work?

Standing at a podium wearing an outfit, I announce: “Take a picture with a real Indian. Take a picture here, in Washington, D.C. on this beautiful Monday morning, on this holiday called Columbus Day. America loves to say ‘her Indians.’ America loves to see us dance for them. America likes our arts and crafts. America likes to name cars and trucks after our tribes. Take a picture with a real Indian. Take a picture here today, on this sunny day here in Washington, D.C.” And then I just stand there. Eventually, one person will pose with me. After that they just start lining up. I’ll do that for a while until I get mad enough or humiliated enough.

It’s dual humiliation.

What are people’s reactions to the performance?

Well, probably the unexpected. I think maybe people would think, “Oh, this is a museum, and its sort of like equal to some Indians grinding corn for us”—or some other cultural demonstration. Or certain places where you can take your picture with an Indian at some sort of event. I’ve seen this actually. I’ve seen other cultural, kinds of icons that you can take your picture with. I was going to do this, but I didn’t have my picture taken with an English guard on the streets of London. It’s not everyday you can get your picture taken with a real Indian.

Do you consider the audience part of the performance?

Yes. The people are getting up there to have their picture taken with an Indian, just like they would have their picture taken with the bull statue on Wall Street. It’s there for the taking. Indian people always have been fair game, and I don’t think people quite understand that we’re not game. Just because I’m an identifiable Indian, it doesn’t mean I’m there for the taking.

But in the long run I’m making a statement for me, and through me, about people’s interaction with American Indians, and the selective romanticization of us.

In your opinion, what is a “real” Indian?

It doesn’t really matter what I am. I know what I am. See, that’s the point. I’ll be in a plane. And someone’s sitting next to me. And they’re looking at me. And they’re wondering what this guy is. And they’ll ask me: “Excuse me sir, are you Native American, are you Indian, or Hawaiian?” I get that a lot too. One of the most troubling questions that I hear is, “Are you full blood?” For me, an Indian is foremost somebody who is culturally Native. They know their tribe, their cultural background and their “Indian ways,” as we would say amongst ourselves.

I’ve also had people come up to me and say, “My grandmother was a Cherokee,” and they don’t look Indian and I disregard it. But when they say, “I’m from Oklahoma, and my uncle was so and so, and I just got back from this place,” then it becomes different because I realize that they’re involved culturally. Does that make it different for me? Yes, because I come from a cultural background. In answer to your question, yes, I am Native. I am an enrolled member of a tribe. I live on a reservation.

Even as the artist, where you ostensibly have the upper hand, it still feels humiliating?

Yes, because that’s part of the work. I never thought about that. I think if I thought about some of these things I wouldn’t do them. But when I get up there, and I’m standing there, and people are trying to talk to me, and they’re smiling, and I’m stoic, . . . I can see the audience. I can see the kind of “Should I? Shouldn’t I? This is going to be great, I’m going to send this back to Europe,” or telling me, “You know my great, great grandfather was a Cherokee.” I’m just focused. I’m up there for everybody to see. In some ways you’re vulnerable physically. People want to put their arms around you, or want you to break that stoic look and smile. Or they say insulting things. After a while I just want to run out of there. But I’m there for a purpose and so that’s part of, I guess, being an artist.

I just think that people should know that this isn’t a joke.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jess-righthand-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jess-righthand-240.jpg)