Portugal’s Soulful Sound

Often compared to American blues, fado is gaining global appeal

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fado-mariza_388.jpg)

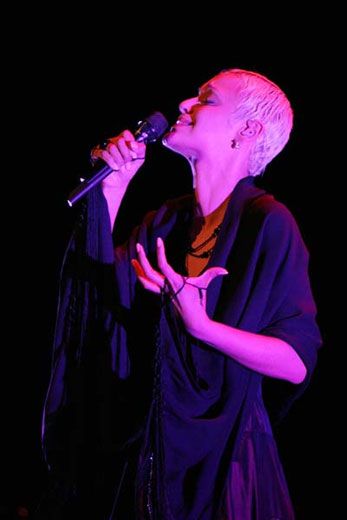

She sweeps in with regal dignity, the very image of a diva, her sumptuous black dress gently caressing the stage floor, her short, light blond hair and slim figure making an arresting sight.

Mariza, the internationally known Portuguese singer, is at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C., captivating yet another audience with the haunting sounds of fado—the music called the soul of Portugal and often compared to American blues. As her voice fills the hall—alternately whispering and shouting, rejoicing and lamenting—the wildly receptive audience confirms her rising reputation as the new queen of fado, and the genre's increasing world appeal.

The roots of fado, Portuguese for fate or destiny, are a mystery. But musicologists see it as an amalgam of cultures, especially African and Brazilian, stemming from Portugal's maritime and colonial past, combined with its oral poetry tradition and, possibly, some Berber-Arab influence from the long Moorish presence that spanned the 8th through the 13th centuries.

Given the history, Mariza seems uniquely suitable to perform it. Born in Mozambique while it was still a Portuguese colony, of an African mother and a Portuguese father, she grew up in Mouraria, the old Moorish district of Lisbon, and started singing fado in her parents' taverna when she was only five.

"I grew up surrounded by fado," she says. "It's more than music, it's my life. It's the way I can explain what I feel about my world, my city, my country, my generation and our future."

In the 19th century, fado became popular among the urban poor of Lisbon. It was sung in bars, back streets and brothels. "Fado was our newspaper," says Mariza, "because it came from sailors and working places, and people didn't know how to read."

Regarded as disreputable by the middle and upper classes, it became nationally known through a tragic love affair. Maria Severa, a 19th-century fado singer from the Lisbon district of Alfama, had a passionate liaison with a nobleman, Conde de Vimioso. The affair ended badly, with Severa dying at age 26, either from suicide or tuberculosis. But the scandal increased fado's appeal, leading to the publication of its first sheet music.

Fadistas, as fado singers are known, often wear a black shawl of mourning, as Severa did after her heartbreak. Her story epitomizes fado's connection with saudade, "a feeling of longing or nostalgia," says Manuel Pereira, cultural counselor of the Portuguese embassy in Washington, "that maybe you can't even define, to miss your home, people or a lost love—always with tragedy attached."

Until the early 20th century, fado was the domain mostly of Lisbon and Coimbra, a town with an eminent university, whose genre is more restrained and sung primarily by men.

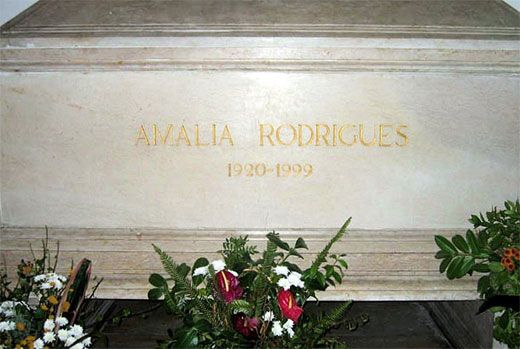

It took another woman from the wrong side of the tracks to make it a national and an international phenomenon. Amália Rodrigues, born in 1920 also in Alfama, is the undisputed icon of fado. Through recordings, films and appearances around the world, her passionate voice made fado (she called it "a lament that is eternal") synonymous with Portugal, and gave it a unique place in the hearts of her countrymen. When she died in 1999, Lisbon declared three days of national mourning; a year later her remains were moved to the National Pantheon, the resting place of royals, presidents and outstanding cultural figures.

During some of Rodrigues' years of stardom, however, fado itself experienced a period of disfavor. Longtime dictator António de Oliveira Salazar, suspicious of the fadistas, first tried to have them censored, then launched a campaign to make fado an instrument of his regime, using it to push his agenda. The result was that many Portuguese turned away from fado, identifying it with fascism.

It took several years after the fall of the regime for the soulful music to again rise in the esteem of its countrymen. In the last 20 years, a new generation of fadistas reinvigorated it and made it once again part of the national fabric, at the same time adapting it to their own experiences.

"While still respecting the traditions of fado," says Mariza, "I'm singing more and more with the influences I've been receiving—travel, listening to other music—and this affects my performance." In addition to the traditional 12-string guitar (guitarra Portuguesa) and bass and acoustic guitars, she often includes trumpets, cellos and African drums. She has branched out to other musical forms, including American blues ("They too explore the feelings of life," she says) and has sung with such luminaries as Sting and Peter Gabriel.

But to her countrymen, it is the old fado that matters. Watching her at the Kennedy Center, Manuel Pereira felt a wave of saudade. "For me and other Portuguese people abroad when we hear fado it is a big emotion," he says. "It moves us."

Dina Modianot-Fox wrote about the return of port for Smithsonian.com earlier this month.