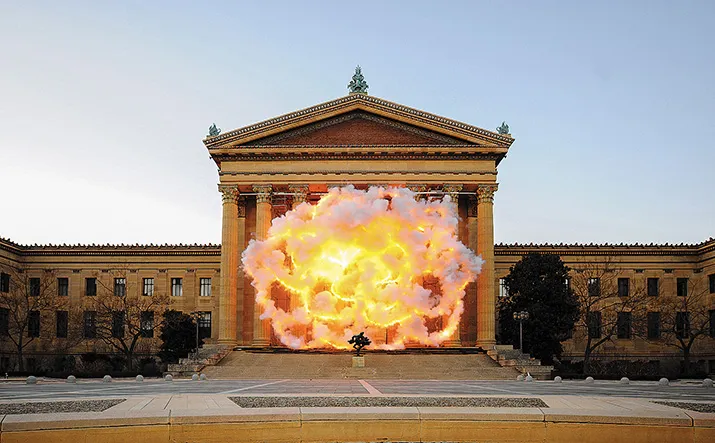

Meet the Artist Who Blows Things Up for a Living

With ethereal artworks traced in flames and gunpowder, Cai Guo Qiang is making a big bang

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Burning-Man-Cai-Guo-Qiang-631.jpg)

Internationally lauded “explosives artist” Cai Guo-Qiang has already amassed some stunning stats: He may be the only artist in human history who has had some one billion people gaze simultaneously at one of his artworks. You read that right, one billion. I’m talking about the worldwide televised “fireworks sculpture” that Cai Guo-Qiang—China-born, living in America now—created for the opening of the Beijing Olympics in 2008. If you’re one of the few earthlings who hasn’t seen it, either live or online, here’s Cai’s description: “The explosion event consisted of a series of 29 giant footprint fireworks, one for each Olympiad, over the Beijing skyline, leading to the National Olympic Stadium. The 29 footprints were fired in succession, traveling a total distance of 15 kilometers, or 9.3 miles, within a period of 63 seconds.”

But a mere billion pairs of eyes is not enough for Cai’s ambition. He’s seeking additional viewers for his works, some of whom may have more than two eyes. I’m speaking of the aliens, the extraterrestrials that Cai tells me are the real target audience for his most monumental explosive works. Huge flaming earth sculptures like Project to Extend the Great Wall of China by 10,000 Meters, in which Cai detonated a spectacular six-mile train of explosives, a fiery elongation of the Ming dynasty’s most famous work. Meant to be seen from space: He wants to open “a dialogue with the universe,” he says. Or his blazing “crop circle” in Germany, modeled on those supposed extraterrestrial “signs” carved in wheat fields—a project that called for 90 kilograms of gunpowder, 1,300 meters of fuses, one seismograph, an electroencephalograph and an electrocardiograph. The two medical devices were there to measure Cai’s physiological and mental reactions as he stood in the center of the explosions, to symbolize, he told me, that the echoes of the birth of the universe can still be felt in every molecule of every human cell.

Maybe there’s the sly wink of a showman behind these interspatial aspirations, but Cai seems to me to be distinctive among the current crop of international art stars in producing projects that aren’t about irony, or being ironic about irony, or being ironic about art about irony. He really wants to paint the heavens like Michelangelo painted the Sistine Chapel ceiling. Only with gunpowder and flame.

When I visit Cai (as everyone calls him, pronouncing it “Tsai”) in his spare East Village Manhattan studio with a big red door and a feng shui stone lion guarding the entrance within, we sit at a glass table flanked by wall-size wood screens: his gunpowder “drawings.” These are large white surfaces upon which Cai has ignited gunpowder to make unexpectedly beautiful black traceries, works of abstract art that remind one of the intricate signage of traditional Chinese calligraphy or those photo negative telescopic prints of deep space in which the scattered stars and galaxies are black on white. Violence transformed into ethereal beauty.

Cai, who looks younger than his mid-50s, fit, with a severe brush-cut of hair, is joined by a translator and project manager, Chinyan Wong, and we are served tea by a member of his artmaking collective as we begin talking about his childhood. He tells me a story of profound family sorrow during the Cultural Revolution—and the “time bomb” in his house.

“My family lived in Quanzhou, across the strait from Taiwan,” he says, where it was routine to hear artillery batteries firing into the mist at the island the mainland regime wanted to reincorporate into China.

“These were my first experiences of explosions.

“My father,” Cai says, “was a collector of rare books and manuscripts,” and an adept at the delicate art of calligraphy. But when the Cultural Revolution began in the mid-’60s, Mao Zedong turned his millions of subjects against anyone and any sign of intellectual or elite practices, including any art or literature that was not propaganda.

“Intellectuals” (meaning just about anyone who read, or even possessed, books) were beaten, jailed or murdered by mobs and all their works burned in pyres. “My father knew his books, scrolls and calligraphy were a time bomb in his house,” Cai recalls. So he began burning his precious collection in the basement. “He had to do it at night so that no one would know.”

Cai tells me that after burning his beloved manuscripts and calligraphy, his father went into a strange self-exile, afraid that his reputation as a collector of books would lead to his death. He left his family home and found a perilous refuge in a ruined Buddhist nunnery where the last remaining 90-year-old devotee gave him sanctuary. There—and this is the especially heartbreaking part—“my father would take sticks and write calligraphy in puddles on the ground,” Cai says. “The calligraphy would disappear” when the water evaporated, leaving behind, Cai once wrote, eloquently, “invisible skeins of sorrow.” Not entirely invisible, one senses, but inscribed like calligraphy on his son’s memory and heart.

His father’s art echoes in his son’s—calligraphy in water and now in fire. In using the deadly gunpowder, he is seeking to transform it from its lethal uses to the ethereal art of calligraphy. This is not just a vague concept: If you happened to find yourself outside the Smithsonian’s Sackler Gallery this past December, you could have seen Cai ignite a pine tree with gunpowder packets on the branches and transform it into an ethereal tree, a tree-shaped tracery of black smoke etched into the sky by black gunpowder ink.

Instead of his father’s Marxism, Cai says, his great influence was Chinese Taoist spirituality. Feng shui, Qi Gong and Buddhism play a role as well, their roots intertwined. He has written of a shaman he knew as a youth who protected him, and of his search for shamans in other cultures. “Spiritual mediums,” he tells me, “channel between the material world and the unseen world to a certain degree similar to what art does.” And he sees his art serving as a similar kind of channel, linking ancient and modern, Eastern and Western sensibilities. Feng shui and quantum physics.

He still believes in “evil spirits,” he says, and the power of feng shui to combat them. When I ask him about the source of the evil spirits the stone lion is guarding us from, he replies that they are “ghosts of dissatisfaction.” An interesting reconceptualization of evil.

For instance, he tells me that he was working on a project that involved the microbes in pond water, but brought it to a halt when a shaman warned him that “the water might contain the spirits of people who might have drowned or tried to kill themselves in the pond.”

As a youth, he says, “I was unconsciously exposed to the ties between fireworks and the fate of humans, from the Chinese practice of setting off firecrackers at a birth, a death, a wedding.” He sensed something in the fusion of matter and energy, perhaps a metaphor for mind and matter, humans and the universe, at the white-hot heart of an explosion.

***

By the time of the political explosion of Tiananmen Square in 1989, Cai had left China and was in Japan, where “I discovered Western physics and astrophysics.” And Hiroshima.

The revelation to him about Western physics, especially the subatomic and the cosmological Big Bang levels, was that it was somehow familiar. “My Taoist upbringing in China was very influential, but not until I got to Japan did I realize all these new developments in physics were quite close to Chinese Qi Gong cosmology. The new knowledge of astrophysics opened a window for me,” he says. The window between the mystical, metaphorical, metaphysical concepts of Taoism—the infinity of mind within us and that of the physical universe whose seemingly infinite dimensions outside us were being mapped by astrophysicists. For example, he says, “The theory of yin and yang is paralleled in modern astrophysics as matter and antimatter, and, in electromagnetism, the plus and minus.”

It was in thinking about the Big Bang that he made what was, to me at least, his most revelatory and provocative connection—that we were all there together at the Big Bang. That every particle in every human being was first given birth when the Big Bang brought matter into being. The unformed matter that would eventually evolve into us was all unified oneness at the moment of the Big Bang.

And it was in Japan that he found a focus also on the dark side of big bangs: Hiroshima and Nagasaki. And began what has been a lifelong artistic attempt to come to terms with that dark side. When he went to Hiroshima, he says, he felt the “essence of spirits there.”

I know what he means. I had been to Hiroshima researching a recent book on nuclear war (How the End Begins: The Road to a Nuclear World War III) not long before Cai had done one of his signature works there. And Hiroshima is strange in its weird serenity. The actual bomb site has been covered over with smoothly rolling lawns (although there are also museums that can give you all the nuclear gore you want). But in general, it’s a peaceful place. Aside from one skeletal dome-topped remnant of a civic structure, there is little trace of the blast that changed the world.

Yet at night you can sense those spirits Cai speaks of. I’d never felt anything so uncanny.

Cai has created “mushroom clouds” over the Nevada atomic testing grounds site and in many other locations across the United States. Mushroom clouds of non-radioactive smoke. Somehow, he hopes, they will exorcise the real mushroom clouds of the past and the potential ones of the future.

But he had trouble, he tells me, with his original plans for Hiroshima, a project he first designed for the 1994 Asian Games. It involved a black cloud descending in a kind of parachute to land harmlessly on Hiroshima’s ground zero. “The idea,” he says, “was meant to suggest that fire descending from the sky has the potential to initiate rebirth. But it faced strong objection...and I had to give up the proposal.”

So he went back to the drawing board and would later win the Hiroshima Art Prize for one of his most brilliant creations, The Earth Has Its Black Hole Too. “This explosion project was realized at Hiroshima central park,” he has written, near “the target of the atomic bomb. I dug a deep hole in the ground at the center of the park and then I used 114 helium balloons at various heights to hold aloft 2,000 meters of fuse and three kilograms of gunpowder, which together formed a spiral with a 100-meter diameter, to mimic the orbits of heavenly stars. The ignition kicked off then from the highest and outermost point to the spiral, burning inward and downward in concentric circles, and disappeared into the ‘black hole’ in the center of the park. The sound from the explosion was extremely violent; the bang echoed and rocked the entire city. My intention was to suggest that in harnessing nuclear energy, humanity has generated its own black hole in the earth that mirrors those in space.”

It was a daring, explosive commemoration of sorrow that surpassed even the spectacle of the Olympics and its celebration of strength. He created a kind of inverse nuclear blast at the very site of the death weapon’s impact.

In one of his earliest projects, “I wrote [an alternate history] in which the secret of nuclear power was discovered by physicists but they decided not to use it to make weapons,” he said, and then faxed the fantasy to art galleries and a far-flung list of political luminaries.

We talk further about nuclear weapons. I ask him a question that has pervaded discussion in the controversies I wrote about: exceptionalism. Are nuclear weapons just exponentially more powerful than conventional weapons or is the difference so great they must be judged by different rules of “just war morality,” military strategy and urgency of abolition?

Cai makes the important point that nukes can’t be judged like the use of other weapons because of one key factor: time. “With the release of energy in traditional explosions the energy is dissipated quickly. With nuclear weapons there is constant preservation of its effects”—nuclear isotopes persist in emitting poisonous radiation for many lifetimes of half-lives.

Nuclear weapons rule over time as well as space. Cai also has a shrewd awareness of one of the key problems of nuclear strategy: deterrence theory. Referring to the subtitle of my book, The Road to a Nuclear World War III, he asks, “Couldn’t it be said that it is because of nuclear weapons there will be no World War III?”

In other words, only the possession of nuclear weapons by more than one nation can deter the use of nuclear weapons. It’s a position taken by many nuclear strategists, though one that depends on faith in human rationality and the absence of catastrophic accidents.

He speaks worriedly about how this will apply to another potential nuclear flash point: the periodic spikes in tension between China and Japan over the disputed islands in the seas between the two countries. The Chinese claims to the Japanese-occupied islands have resulted in a counter-movement in Japan by some politicians to amend their constitution to allow them to possess nuclear weapons (mainly to deter a potential Chinese nuclear threat).

***

Cai returned to Japan to make nuclear power the subject of his art in the wake of the 2011 Fukushima nuclear plant disaster. The challenge for him was to make the invisible visible. “The problem is that you cannot see all the radioactive waves the way you can see the smoke left behind by gunpowder,” he explains. He found a somewhat terrifying but creepily beautiful way of making the invisible visible. “I was there to help the inhabitants plant lots and lots of cherry blossom [trees].” Densely packed together so they can be seen from outer space. He’s got 2,000 so far but wants to eventually plant 100,000. What he really seems to hope will happen is that the cherry blossoms will slowly mutate from the radioactivity in the soil, these varied mutations being a way of making visible the invisible poisoning of nature by human nature, a twisted artistic tribute to the mangled beauty that had been ravaged and could be reborn in strange ways.

It’s a breathtaking idea. I’m not sure I’d want to find myself lost in that twisted mutant forest, though I’m sure it would heighten the consciousness of anyone who ventures in or even sees it from a distance.

If it proceeds, he will have found a way to express tragedy through visual art inscribed on the planet, inscribed in the plants’ DNA. It may be a conceptual rather than strictly biological vision. “Some mysteries are meant to be [discovered],” he says, “Some are meant to be heaven’s secrets.”

I’m not exactly clear which is which, but Cai adds that “I try to use my art as a channel of communication between man and nature; man and the universe. Who knows where this channel brings you?”

I ask him what channel brought him to America in the mid-1990s (although he’s frequently traveling all over the world to blow things up). He says that while he was in Japan he learned about recent developments in American art, including the work of people he came to admire, like Robert Smithson, who had made grand earth-altering landscape projects like Spiral Jetty in the American desert. But the real reason he resolved to move to the United States was “because of NASA,” he says. “I was attracted to anything that would bring me closer to the universe—and the universe closer to me.”

He says that what continues to fascinate him about America are its contradictions. “I wanted to live and work in a country that is most problematic in the 20th century,” he says, “and offer a completely different point of view.”

So I ask him, having looked at civilizations from both sides now, from East and West, does he have any lessons that Westerners can learn from the East?

He is not hesitant. It might help Westerners to learn, he suggests, that “Many things don’t have an immediate solution, and many conflicts cannot be resolved immediately. Sometimes things take time to heal and when you take a longer time you might be better able to accomplish your goal.

“So in art and artistic expression,” he continues, “the things you’re trying to relay, they can be full of conflict, and you do not necessarily have to use art to resolve all these conflicts. As long as you acknowledge these conflicts or address the conflict in your art, that is already meaningful.”

It makes me think of the poet John Keats’ idea of “negative capability”: the distinction of a first-rate mind is that it can entertain conflicting ideas, “is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts without any irritable reaching” after certainty.

When we finish our conversation and I join the members of his collective for a lunch of many dishes Eastern and Western, Cai tells me about his continuing dream project, in which he goes around the world (next stop, Brazil) creating a “ladder to the sky” of fire in the air above the earth, symbolizing his desire to invite extraterrestrials to descend, or for us to ascend to meet them.

As I leave, I pat the head of the stone lion, hoping the beast will protect us should the aliens Cai is inviting turn out to have less than benign intentions.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ron-rosenbaum-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ron-rosenbaum-240.jpg)