The Mad Challenge of Translating “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”

Explore the linguistic tricks used to make Lewis Carroll’s puns, parodies and nonsense accessible in hundreds of tongues

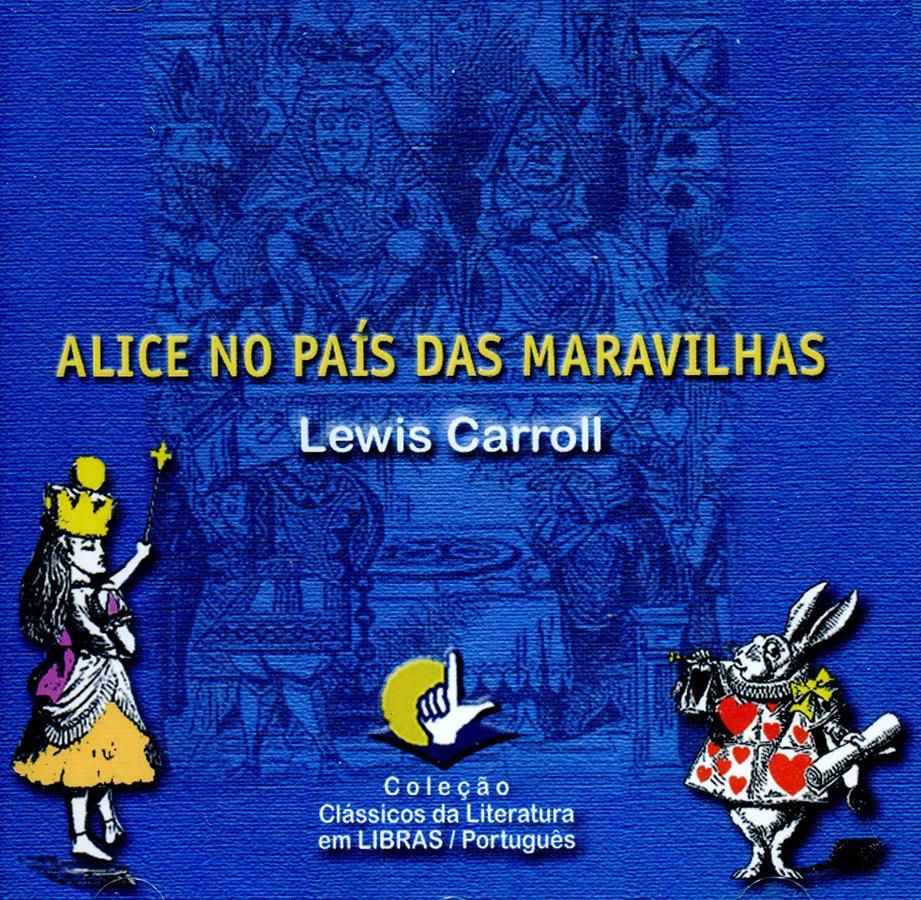

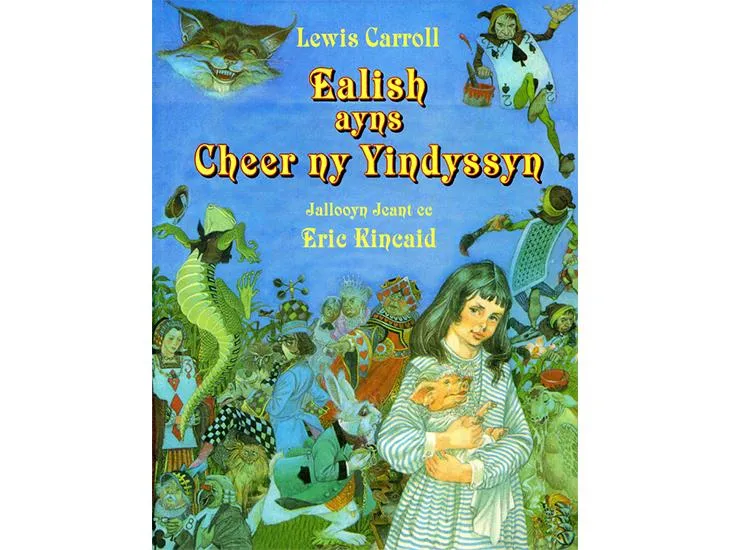

Middle Welsh and Manx, Lingwa de Planeta and Latgalian. In its 150-year history, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland has been translated into every major language and numerous minor ones, including many that are extinct or invented. Only some religious texts and a few other children’s books—including The Little Prince by French writer Antoine de Saint-Exupéry—reportedly rival Alice for sheer number of linguistic variations.

But the real wonder is that any Alice translations exist at all. Penned in 1865 by English scholar Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, aka Lewis Carroll, the book’s delight in wordplay and cultural parodies makes it a torment for translators.

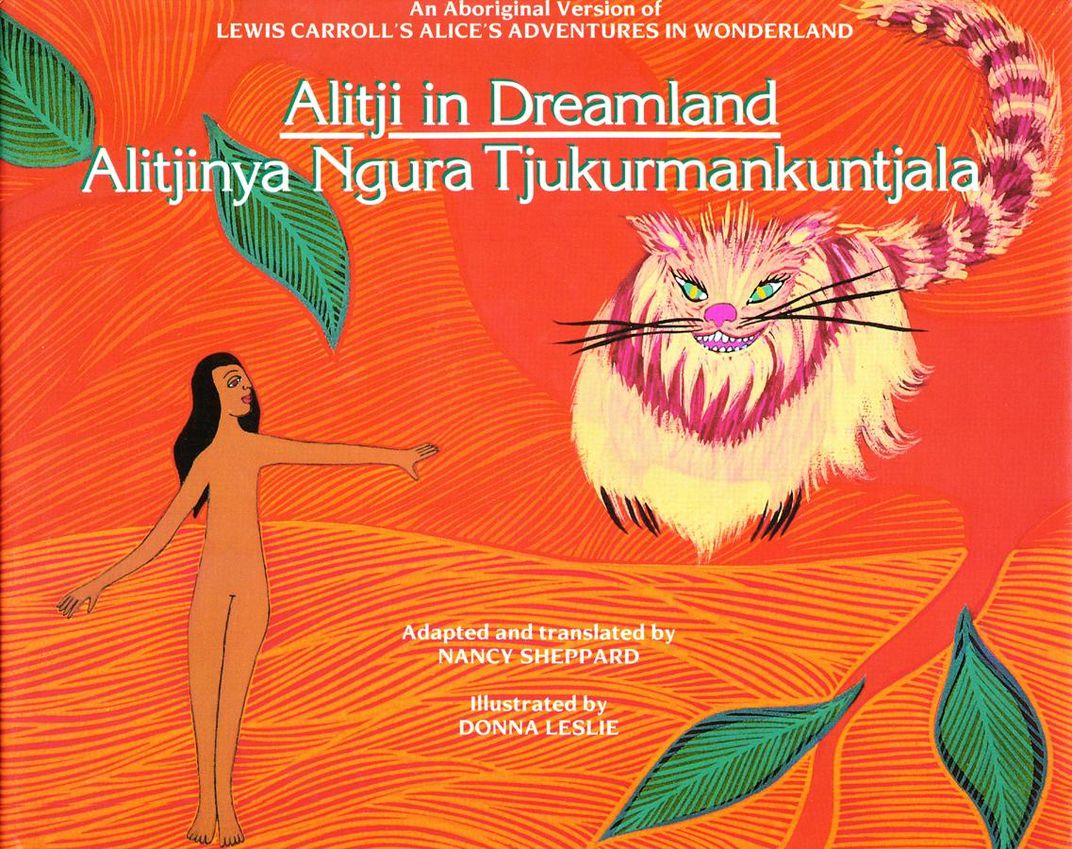

How do you write about the Mouse’s tale without losing the all-important pun on “tail”? Some languages, like the Aboriginal tongue Pitjantjatjara, don’t even use puns. What about when a character takes an idiom literally? The Caterpillar, for instance, tells Alice to explain herself. “I can’t explain myself, I’m afraid, sir, because I’m not myself, you see,” Alice replies. The cultural references in this Victorian novel pose other problems. British contemporaries would have guessed that the Hatter was mad from mercury exposure, but hat makers in other parts of the world didn’t use mercury. And why translate a parody of a popular British poem for readers of Arabic who have never seen the original?

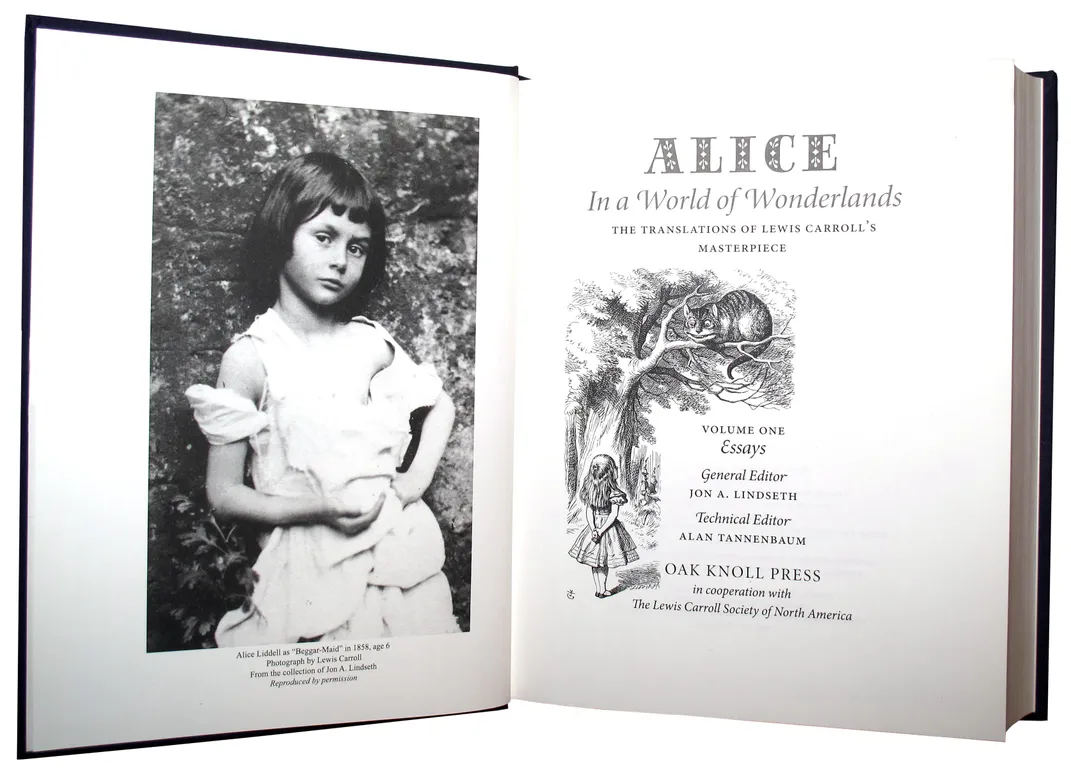

A massive new work, Alice in a World of Wonderlands, devotes three volumes to exploring such questions. Published by Oak Knoll Press, the books include essays by 251 writers analyzing the beloved children's book in 174 languages. The essays are scholarly but peppered with anecdotes illuminating the peculiarities of language and culture as they relate to Carroll’s book.

The project began as a catalog to accompany an exhibition on Alice translations, which is opening at the Grolier Club in New York City in September. “It’s gotten bigger by a long shot,” says general editor Jon Lindseth, whose extensive collection of Alice books inspired the undertaking. “We're putting a stake in the sand and making the claim that this is the most extensive analysis ever done of one English-language novel in so many languages.”

Language and typography scholar Michael Everson says the novel’s inherent difficulty is part of its appeal. “The Alice challenge seems to be one that people like because it’s really fun,” he says. “Wracking your brains to resurrect a pun that works in your language even though it shouldn't, that sort of thing.” For instance, an early Gujarati translator managed to capture the tail/tale pun for readers of that western Indian tongue. When someone talks incessantly, it is often conveyed through the Gujarati phrase poonchadoo nathee dekhatun, which means “no end in sight"—allowing the translator to play on poonchadee, the word for "tail", with poonchadoo.

Everson owns Evertype, a publishing house that specializes in esoterica. Under this banner, he has published 50 editions of Alice, including one in Gothic, an extinct Germanic language, and one in Nyctographic, an alphabet Carroll invented. Everson himself is currently translating Alice into Blissymbols, a visual language that's been adapted for people who lack the ability to speak. “I’m using visual puns where possible, because there’s no phonology,” Everson says.

His approach illustrates something common to all successful Alice translations. “You have to be really creative in order to translate Alice in Wonderland well,” says Emer O’Sullivan, an expert on children’s literature in translation at Leuphana University in Lüneburg, Germany. “The translations with zero creativity are really quite hilarious.”

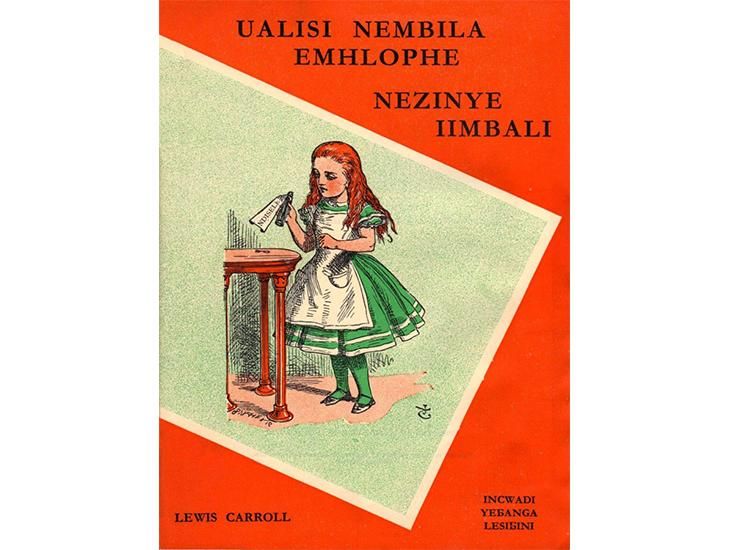

The mad tea party scene, with its puns, parodied verses, nonsense and linguistic jokes, is a particularly good test of a translator’s skills. Some simply omit parts of the scene—for South African readers, the Xhosa translator dispenses with the chapter altogether. In the second volume of Alice in a World of Wonderlands, the scene has been back-translated—re-translated into English—from each language, with copious footnotes. The results show how different translators approach the same problem.

Take Carroll’s parody of “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star,” recited at the tea party by the Hatter:

Twinkle, twinkle, little bat!

How I wonder what you’re at!

Up above the world you fly

Like a tea-tray in the sky.

Here it is back-translated from Pashto, an Afghani language:

Blink, oh, you little bat,

Tell me something about your situation because I am surprised.

Open your wings on the world,

Like a Falcon in the sky.

The Pashto translator notes that he rewrote the poem to make it rhyme properly but otherwise tried to match the original English. In other words, he faithfully rendered Carroll’s parody in Pashto despite the fact that “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” is not a traditional work in Afghanistan. This is known among translators as the foreignization strategy: the translator stays close to the original text at the risk of producing something readers will not fully understand.

The 1869 German version, by contrast, dispenses with the twinkling star entirely, as is evident in the back-translation:

O parrot, o parrot!

How green are your feathers!

You’re not only green in times of peace,

But also when it snows plates and pots.

Here the translator chose to parody a German Christmas carol his readers would know, “O Tannenbaum,” in a strategy known as domestication. To make the poem culturally and linguistically relevant to her readers, the translator sacrificed a literal interpretation of Carroll’s words. This is a common approach among Alice translators, some to a greater degree than others. In the Swahili edition, the Hatter wears a fez and the dormouse is a bush baby. In a 1910 Japanese edition, the Hatter does not offer Alice tea. An annotation notes that this is likely because it was inappropriate for men to serve food or drinks to women in Japan at the time. Other translations alter so much that readers may wonder how much of the original Alice remains.

“There's so many things in Alice in Wonderland you could identify as being Carrollian,” says O’Sullivan. “How many of them would have to be fulfilled for you to say this is Alice in Wonderland? It’s a question of degree. All translations are adaptations.”

While the three volumes of Alice in a World of Wonderlands may seem extensive, they are no match for the continuing popularity of Carroll’s creation. Even now, new Alice translations are appearing. An emoji version came out online a few months ago, and Everson says he just typeset the first translation in Western Lombard, a dialect spoken in Italy. “I hate to say it,” he says, “I think [the project is] already out of date.”

Note: This article has been updated to reflect the fact that scholars can only verify 46 translations of Pinocchio as of 1994.