Ken Kesey’s Pranksters Take to the Big Screen

It took an Oscar-winning director to make sense of the drug-addled footage shot by the author and his Merry Pranksters

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Magic-Trip-Ken-Kesey-on-bus-631.jpg)

Before there was a Summer of Love, before the phrase “Turn on, tune in, drop out” became a counterculture rallying cry, before Easy Rider and the Grateful Dead, Ken Kesey set out on a journey to free America from a society he believed had grown intolerant and fearful. The success of his novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, whose anti-hero Randle McMurphy rebelled against conformity, gave Kesey the financial freedom to test his theories in public.

In 1963, the author was in New York attending rehearsals of a Broadway adaptation of Cuckoo’s Nest when he came up with the idea of leading a cross-country bus trip from California to the world’s fair, which would open the following year in New York. He was inspired in part by On the Road, the 1957 novel by Jack Kerouac that raised “road trip” to an art form. Kesey would use his journey not only to discover a “real” America where rugged individualism and a frontier ethos still reigned, but to show a new way to live, one free of outdated norms and conventions.

Back in California, Kesey and his friends, who would call themselves “The Merry Band of Pranksters,” outfitted a school bus for the journey, adding a generator, building a rooftop turret, and daubing the bus with psychedelic paint. Kesey cemented his connection to Kerouac by asking Neal Cassady to fill the “Dean Moriarty” role from On the Road and drive the bus.

The Pranksters’ journey led them through the deserts of Arizona to the Louisiana bayous, from the Florida Everglades to the streets of Harlem. Along the way Kesey met with the Beats and with Timothy Leary, but found their vision of society as disappointing as the corporate future on display at the world’s fair.

Kesey purchased state-of-the-art 16-millimeter motion picture cameras and crystal-synch tape recorders to document his journey. The resulting 40 hours of film and audio form the basis of Magic Trip: Ken Kesey’s Search for a Kool Place, a new documentary directed by Alex Gibney and Alison Ellwood.

Gibney points out that none of Kesey’s footage had been screened properly before. For one thing, filming during the trip was a haphazard process. “They were farm kids,” Gibney (whose films include Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room and the Oscar-winning Taxi to the Dark Side) explains. “They had great confidence in machinery, and a great skepticism of experts.” The Pranksters felt they could figure out the equipment themselves, and in fact did manage to achieve good exposures with the notoriously difficult 16-millimeter reversal stock. But they never mastered synchronizing their sound to film.

“Every time you run a camera and an audio recorder simultaneously, you have to make a synch point,” Gibney says. “Over the 100 hours of footage, Kesey’s people did that exactly once, when they hired a professional sound person in New York, who would put up with them for only one day. My co-director and editor Alison Ellwood had to comb through the footage looking for a bump or a clap or someone pronouncing ‘p’ in order to find a synch point. But even when she did, there was another problem. Since the Pranksters were running the recorder off the bus generator, which would pulse according to how fast they were driving, the sound and picture would go out of synch almost immediately. We even hired a lip reader at one point to help.”

And while Kesey showed some of the footage during his “Acid Trip” parties immortalized in Tom Wofle’s best-selling 1968 book The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, for the most part, the films and audiotapes remained in storage. By the time Kesey’s son Zane granted Gibney access to the material, it had suffered from decades of neglect. Backing from the Film Foundation helped pay for restoration and preservation work at the UCLA Film and Television Archives.

What Gibney and Ellwood discovered when the footage was finally ready for editing was more than a time capsule and more than a nostalgic trip back to the ’60s. For all their miscues and technical glitches, Kesey and the Pranksters recorded an America on the verge of tremendous change, but also a country surprisingly open and friendly to a ragtag group of wanderers. “Hippies” had yet to be defined, drugs were still under the radar and observers seemed to be bemused rather than threatened by the Pranksters. Gibney notes that they were stopped by police a half-dozen times, but never received a traffic ticket—even though Cassady lacked a driver’s license.

“What they were doing was glorious, fun and magical in the best sense of the word,” Gibney says. The director sees Kesey as an artist and adventurer who was at heart a family man, the coach of his local school football and soccer teams. “In a way, the bus trip is kind of Kesey’s art piece,” Gibney argues. “I think part of his mission was to be a kind of Pied Piper for a country that was just enveloped in fear. He was saying, ‘Come out of your bomb shelter. Have fun. Don’t be trapped in a maze.’”

Gibney agrees that Kesey was attracted to the chaos of the journey, a chaos amplified by the extraordinary amounts of drugs consumed by the Pranksters.

Unlike many of his followers, Kesey tried to use drugs to explore his personality, not to repeat the same experiences. “You take the drug to stop taking the drug,” he said.

“He was talking about enlightenment,” Gibney explains. “At one point Kesey says, ‘I didn’t want to be the ball, I wanted to be the quarterback.’ He’s trying to gently guide this trip to become a sort of mythic journey rather than just, you know, a keg party.”

In execution, the trip turned into an extended binge, with the Pranksters using any excuse to drink, smoke and drop acid. Early on Cassady swerves the bus off an Arizona highway into a swamp. Kesey and his companions take LSD and play in the muck while waiting for a tow truck to rescue them. Whether visiting author Larry McMurtry in Texas or poet Allen Ginsberg in New York, the Pranksters—as their name implies—become a disruptive force, leaving casualties behind as they set off on new adventures. For viewers today who know the effects of hallucinogens, the sight of Kesey passing around a carton of orange juice laced with LSD is chilling.

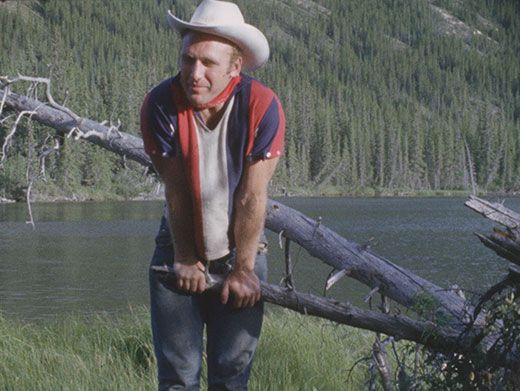

Kesey and his companions returned to California by a different route, a slower, more contemplative journey. Gibney likes this section of the film best. By now the camerawork, so frustrating in the opening passages, feels more accomplished. The imagery is sharper, the compositions tighter. The Pranksters detour through Yellowstone, drop acid by a mountain lake in the Rockies, and drift through beautiful but secluded landscapes. Back at his ranch at La Honda, California, Kesey would screen his film at extended "Acid Test" parties, where the music was often provided by a group called the Warlocks-soon to evolve into the Grateful Dead.

Gibney came away from the project with a greater appreciation for Kesey’s presence. “He’s a Knight of the Round Table and a comic book figure all at once, a classic American psychedelic superhero. He’s got the barrel chest of a wrestler, and when he puts on a cowboy hat, he’s like Paul Newman. But there’s always something bedrock, Western, sawmill about the guy.”

Magic Trip lets you participate vicariously in one of the founding moments of a new counterculture. Directors Gibney and Elwood give you a front row seat to the all-night drives, bleary parties, sexual experimentation, mechanical breakdowns, breathtaking vistas, Highway Patrol stops and even the occasional compelling insight into society and its problems. In a sense this is where hippies started, and also where their movement started to fail.

Magic Trip opens Friday, August 5, in selected cities, and is also available on demand at www.magictripmovie.com.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/daniel-eagan-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/daniel-eagan-240.jpg)