How the Polaroid Stormed the Photographic World

Edwin Land’s camera, the SX-70, perfected the art of instant gratification

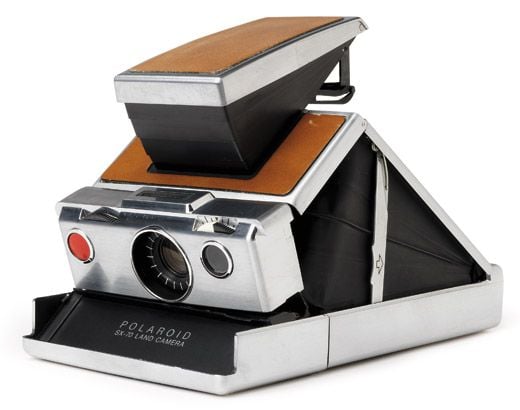

I first saw the Polaroid SX-70—the one-step instant camera introduced in 1972 by the company’s co-founder, Dr. Edwin Land—in the spring of 1973, when the photographer Richard Avedon visited my wife and me on a small Greek island where we lived. Avedon was one of many artists, photographers and celebrities to whom Polaroid provided cameras and film, including Ansel Adams, Walker Evans and Walter Cronkite. Sitting at lunch, Avedon would snap a picture, and with a fun-house whir a blank square would emerge from the front of the camera and develop before our eyes. Had Prospero himself appeared wielding a magic wand, he couldn’t have caused more amazement. According to Sean Callahan, a founding editor of American Photographer magazine, the SX-70 constituted “the most sophisticated and innovative consumer product of its time.”

The genesis of the little wonder machine, the story goes, was that Land’s young daughter asked why she couldn’t see the vacation photos her father was taking “right now.” Polaroid was already a successful optical company; in 1947 Land and his engineers began producing cameras using peel-and-develop film, first black-and-white, then color. Sam Liggero, a chemist who spent several decades as a product developer at Polaroid, told me recently that Land had long envisioned an SX-70-type camera, involving a self-contained, one-step process with no fuss and no mess. Liggero describes Land as someone who “could look into the future and eloquently describe the intersection of science, technology and aesthetics.”

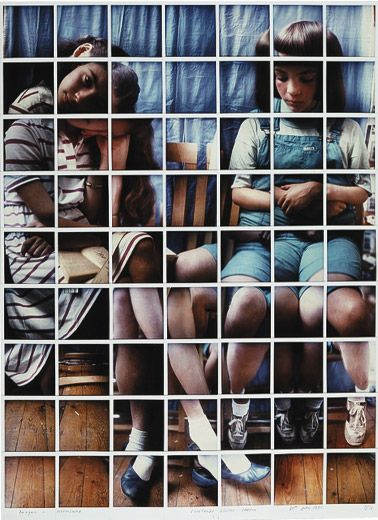

The SX-70—one of which is included in the holdings of the Smithsonian Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum in New York City—embodied that intersection. A documentary about the device, produced for Polaroid by the designers Charles and Ray Eames, called the camera “a system of novelties.” To help shape its form, Land hired Henry Dreyfuss, the industrial designer responsible for such varied products as the classic Bell System “500” series dial phones and John Deere tractors. Unopened, the SX-70 was compact and sleek. An upward tug on the viewfinder readied the camera for action. Internally, the SX-70 was a miracle of physics, optics and electronics, containing 200 transistors and a complex of moving mirrors, light sensors, gears and solenoids. The film was a layered sandwich of chemicals that Polaroid insiders called “the goo.” Artists such as Lucas Samaras were able to manipulate the emulsion to produce impressionistic effects.

Land, who had dropped out of Harvard (“Doctor” was an honorific), saw the SX-70 as the ideal way to remove the “barriers between the photographer and his subject,” as the Eames film puts it. An inventor with hundreds of patents, he considered the camera the most significant product his company launched. Eelco Wolf, international communications manager for the firm at the time of the introduction, told me the SX-70 “really established Polaroid as a credible consumer company.” Released just before Christmas in 1972, the camera was big news. Sean Callahan, then a photo editor at Life magazine, produced a cover story that included images of Land using the SX-70 to photograph kids playing near Boston’s Bunker Hill Monument.

Land was a canny marketer. One day in the spring of 1972, Wolf recalls, he was summoned to Land’s office. On a table lay a prototype SX-70 and a vase of tulips—a variety called Kees Nelis, red on the outside, yellow inside. Land announced that he needed Wolf to order 10,000 of the same tulips for the upcoming shareholders’ meeting, where cameras would be available for the launch announcement. “This was shortly before Easter,” Wolf recalls. “There wasn’t a tulip to be had.” He located a grower in the Netherlands with one field of Kees Nelis blooms still unsold. KLM airlines delivered the thousands of tulips; shareholders, who were issued SX-70s to shoot their tabletop bouquets, were duly impressed. Of course, there was method to Land’s monomania. The film had not yet been perfected: The two colors that showed it to best advantage were red and yellow.

Today, digital photography has passed by the ingenious SX-70. Polaroid produced cameras based on the SX-70 up until the company’s first bankruptcy filing in 2001. Today, the firm, reconstituted and downsized, sells an instant analog camera, in some respects a stepchild of the SX-70.

Land, who died in 1991, was the very model of the inspired entrepreneur, capable of turning imagination into revolutionary reality. “The passion at Polaroid in those days,” recalls Liggero, “there was just nothing like it.”

Owen Edwards is author of the book Elegant Solutions.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)