How Futurist Art Inspired the Design of a BMW

The Italian art movement that celebrated modernity still moves us 100 years later

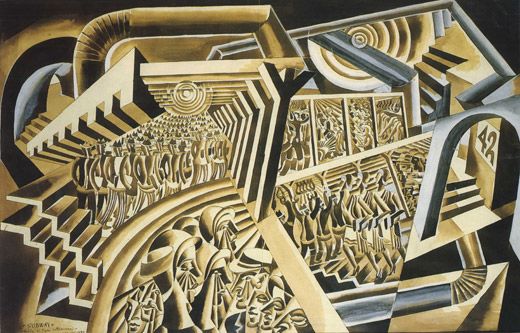

The Futurists stormed Italy in the early 20th century, picking a fight with anything pretty, sentimental or passé. They celebrated violence, speed, masculinity and, above all, modernity.

The art movement’s 2009 centennial brought a rash of retrospectives to Italy and elsewhere. The biggest-ever American exhibition is scheduled to open at the Guggenheim in 2014. Since the Futurists proposed the destruction of museums (“cemeteries,” in their parlance), they would have hated these tributes. But they would have been pleased to discover that their influence remains potent in the 21st century.

In 1909, when Futurism’s father, the poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, penned his first furious manifesto, Italy had been reduced to a European backwater, and it lacked coal, making industrialization painfully slow.

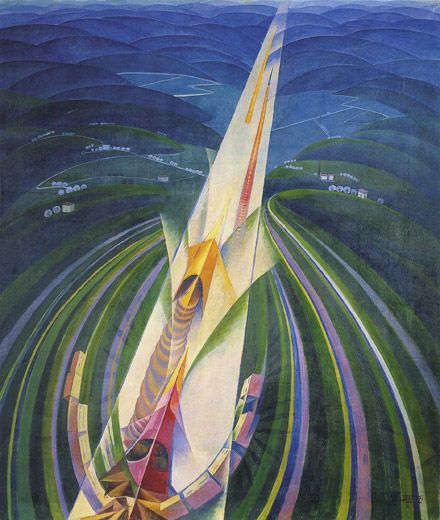

Marinetti scorned the nostalgia for the Renaissance and Rome. “He was tired of hearing about them,” says Christine Poggi, a University of Pennsylvania art historian. He wanted Italians to move on, and to exhalt gritty manufacturing centers, like Milan. He exhorted Italians to find beauty in technology: “A roaring car that seems to ride on grapeshot is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace,” the marble Hellenistic masterpiece.

All types of artists quickly took up the cause and started churning out manifestoes of their own. Among other measures, they declared a ten-year moratorium on the nude in paintings. “It was considered the archetypal subject of the Renaissance, and it was not modern,” Poggi says. Umberto Boccioni, a sculptor who had once painted a semi-nude of his own plump and aged mother, went on to create Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, a striding, muscular bronze figure that is perhaps the marquee Futurist work.

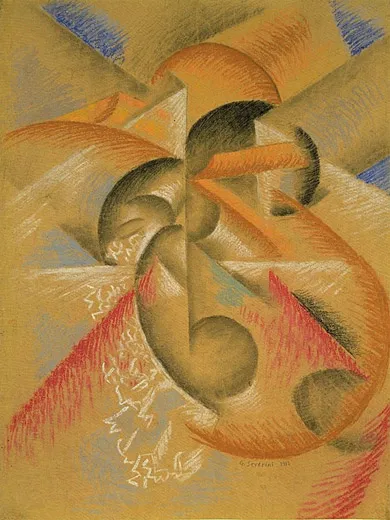

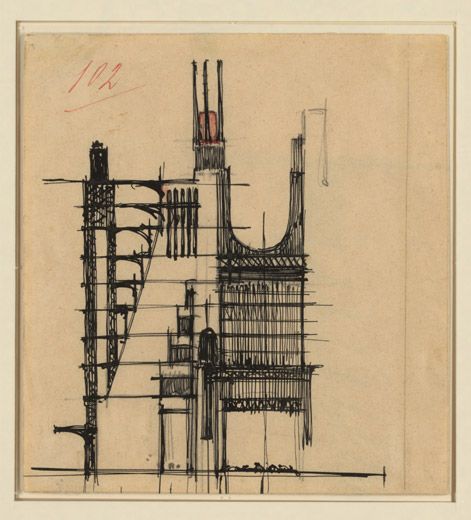

The Futurists depicted hurtling trains, human bodies in motion, machine-gun fire, electric lights and metropolises under construction. Their bold techniques touched everything from Art Deco to Dadaism. The movement still influences “almost any artist interested in kineticism or working with light,” Poggi says. This spring the Italian fashion house Etro is featuring a runway line with patterns inspired by the works of the Futurist Fortunato Depero.

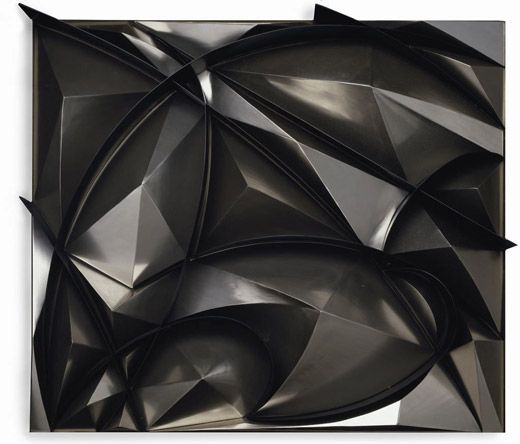

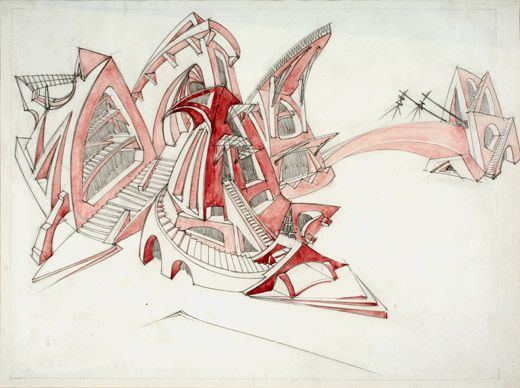

Chris Bangle, the revolutionary chief designer of BMW from 1992 to 2009, says that Boccioni’s sculptures allowed him to see a fourth dimension, “that of the wind.” Bangle created surfaces with a mix of convex and concave curves that exuded agility, such as the GINA Light concept car. Upon the release of the Bangle-era BMW Z4 Coupe in 2006, BusinessWeek observed that it seems to be moving “even when standing still.”

“I think Boccioni would have thought that somebody had finally done honor to what he tried to wrestle out of form and space,” Bangle says. “He would have liked those cars.”