Hopper: The Supreme American Realist of the 20th-Century

Mystery. Longing. A whole new way of seeing. A stunning retrospective reminds us why the enigmatic American artist retains his power

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/31/66/31664fb3-def9-42cf-868f-706a22a36313/hopperx.jpg)

Painting did not come easily to Edward Hopper. Each canvas represented a long, morose gestation spent in solitary thought. There were no sweeping brushstrokes from a fevered hand, no electrifying eurekas. He considered, discarded and pared down ideas for months before he squeezed even a drop of paint onto his palette. In the early 1960s, the artist Raphael Soyer visited Hopper and his wife, Josephine, in their summer house on a bluff above the sea in Cape Cod. Soyer found Hopper sitting in front gazing at the hills and Jo, as everyone called her, in back, staring in the opposite direction. "That's what we do," she said to Soyer. "He sits in his spot and looks at the hills all day, and I look at the ocean, and when we meet there's controversy, controversy, controversy." Expressed with Jo's characteristic flash (an artist herself and once an aspiring actress, she knew how to deliver a line), the vignette summarizes both Hopper's creative process and the couple's fractious yet enduring relationship. Similarly, Hopper's close friend, American painter and critic Guy Pène du Bois, once wrote that Hopper "told me...that it had taken him years to bring himself into the painting of a cloud in the sky."

For all his cautious deliberation, Hopper created more than 800 known paintings, watercolors and prints, as well as numerous drawings and illustrations. The best of them are uncanny distillations of New England towns and New York City architecture, with exact time and place arrested. His stark yet intimate interpretations of American life, sunk in shadow or broiling in the sun, are minimal dramas suffused with maximum power. Hopper had a remarkable ability to invest the most ordinary scene—whether at a roadside gas pump, a nondescript diner or a bleak hotel room—with intense mystery, creating narratives that no viewer can ever quite unravel. His frozen and isolated figures often seem awkwardly drawn and posed, but he eschewed making them appear too graceful or showy, which he felt would be false to the mood he sought to establish. Hopper's fidelity to his own vision, which lingered on the imperfections of human beings and their concerns, made his work a byword for honesty and emotional depth. Critic Clement Greenberg, the leading exponent of Abstract Expressionism, saw the paradox. Hopper, he wrote in 1946, "is not a painter in the full sense; his means are second-hand, shabby, and impersonal." Yet Greenberg was discerning enough to add: "Hopper simply happens to be a bad painter. But if he were a better painter, he would, most likely, not be so superior an artist."

Hopper was as pensive as the people he put on canvas. Indeed, the enigmatic quality of the paintings was enhanced by the artist's public persona. Tall and solidly built with a massive balding head, he reminded observers of a piece of granite—and was about as forthcoming. He was unhelpful to journalists seeking details or anecdotes. "The whole answer is there on the canvas," he would stubbornly reply. But he also said, "The man's the work. Something doesn't come out of nothing." The art historian Lloyd Goodrich, who championed Hopper in the 1920s, thought that the artist and his work coalesced. "Hopper had no small talk," Goodrich wrote. "He was famous for his monumental silences; but like the spaces in his pictures, they were not empty. When he did speak, his words were the product of long meditation. About the things that interested him, especially art...he had perceptive things to say, expressed tersely but with weight and exactness, and uttered in a slow reluctant monotone."

As to controversy, there is little left anymore. Hopper's star has long blazed brightly. He is arguably the supreme American realist of the 20th century, encapsulating aspects of our experience so authentically that we can hardly see a tumbledown house near a deserted road or a shadow slipping across a brownstone facade except through his eyes. Given Hopper's iconic status, it is surprising to learn that no comprehensive survey of his work has been seen in American museums outside New York City in more than 25 years. This drought has been remedied by "Edward Hopper," a retrospective currently at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston through August 19 and continuing on to Washington, D.C.'s National Gallery of Art (Sept. 16, 2007-Jan. 21, 2008) and the Art Institute of Chicago (Feb. 16-May 11, 2008). Consisting of more than 100 paintings, watercolors and prints, most of them dating from roughly 1925 to 1950, the period of the artist's greatest achievement, the show spotlights Hopper's most compelling compositions.

"The emphasis is on connoisseurship, an old-fashioned term, but we selected rigorously," says Carol Troyen, a curator of American painting at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and one of the organizers—along with the Art Institute's Judith Barter and the National Gallery's Franklin Kelly—of the exhibition. "Hopper is recognized as a brilliant creator of images, but we also wanted to present him as an artist dedicated to the craft of painting whose work must be seen in person. His art is far more subtle than any reproduction reveals."

Edward Hopper was born July 22, 1882, in Nyack, New York, 25 miles north of New York City, into a family of English, Dutch, French and Welsh ancestry. His maternal grandfather built the house—preserved today as a landmark and community art center—where he and his sister, Marion, who was two years older, grew up. Hopper's father, Garrett Henry Hopper, was a dry goods merchant. His mother, Elizabeth Griffiths Smith Hopper, enjoyed drawing, and both his parents encouraged their son's artistic inclinations and preserved his early sketches of himself, his family and the local countryside. Gangling and self-effacing, Edward, who was over six feet tall at age 12, was teased by his classmates. His differentness probably reinforced solitary pursuits—he gravitated to the river, to sketching, to sailing and to painting. Even as a child, Hopper recalled, he noticed "that the light on the upper part of a house was different than that on the lower part. There is a sort of elation about sunlight on the upper part of a house."

Although Hopper's parents recognized their son's gifts and let him study art, they were prudent enough to require that he specialize in illustration as a way to make a living. After graduating from high school in 1899, Hopper enrolled in a commercial art school in New York City and stayed there about a year, after which he transferred to the New York School of Art, founded in 1896 by the American Impressionist William Merritt Chase. Hopper continued to study illustration but also learned to paint from the most influential teachers of the day, including Chase, Robert Henri and Kenneth Hayes Miller. Both Chase and Henri had been influenced by Frans Hals, Velázquez and French Impressionism, particularly as exemplified by Édouard Manet. Henri encouraged his students to emancipate themselves from tired academic formulas, espousing a realism that plunged into the seamier aspects of American cities for its subject matter. As a successful artist looking back, Hopper had reservations about Henri as a painter, but he always granted that his teacher was a vigorous advocate for an enlightened way of seeing. Inspired by Henri's motivating force, the youthful Hopper stayed on at the school for six years, drawing from life and painting portraits and genre scenes. To support himself, he taught art there and also worked as a commercial artist. Hopper and his friend Rockwell Kent were both in Miller's class, and some of their early debates turned on painterly problems that remained of paramount fascination for Hopper. "I've always been intrigued by an empty room," he remembered. "When we were at school...[we] debated what a room looked like when there was nobody to see it, nobody looking in, even." In an empty room absence could suggest presence. This idea preoccupied Hopper for his entire life, from his 20s through his last years, as is evident in Rooms by the Sea and Sun in an Empty Room, two majestic pictures from the 1950s and '60s.

Another essential part of a budding artist's education was to go abroad. By saving money from his commercial assignments, Hopper was able to make three trips to Europe between 1906 and 1910. He lived primarily in Paris, and in letters home he rhapsodized about the beauty of the city and its citizens' appreciation of art.

Despite Hopper's enjoyment of the French capital, he registered little of the innovation or ferment that engaged other resident American artists. At the time of Hopper's first visit to Paris, the Fauves and the Expressionists had already made their debuts, and Picasso was moving toward Cubism. Hopper saw memorable retrospectives of Courbet, whom he admired, and Cézanne, about whom he complained. "Many Cézannes are very thin," he later told writer and artist Brian O'Doherty. "They don't have weight." In any case, Hopper's own Parisian pictures gave intimations of the painter he was to become. It was there that he put aside the portrait studies and dark palette of the Henri years to concentrate on architecture, depicting bridges and buildings glowing in the soft French light.

After returning to the United States in 1910, Hopper never visited Europe again. He was set on finding his way as an American, and a transition toward a more individual style can be detected in New York Corner, painted in 1913. In that canvas, he introduces the motif of red-brick buildings and the rhythmic fugue of opened and closed windows that he would bring to a sensational pitch in the late 1920s with The City, From Williamsburg Bridge and Early Sunday Morning. But New York Corner is transitional; the weather is misty rather than sunny, and a throng uncharacteristically congregates in front of a stoop. When asked years later what he thought of a 1964 exhibition of artist Reginald Marsh's work, the master of pregnant, empty spaces replied, "He has more people in one picture than I have in all my paintings."

In December 1913, Hopper moved from Midtown to Greenwich Village, where he rented a high-ceilinged, top-floor apartment at 3 Washington Square North, a brick town house overlooking the storied square. The combined living and work space was heated by a potbellied stove, the bathroom was in the hall, and Hopper had to climb four flights of stairs to fetch coal for the stove or pick up the paper. But it suited him perfectly.

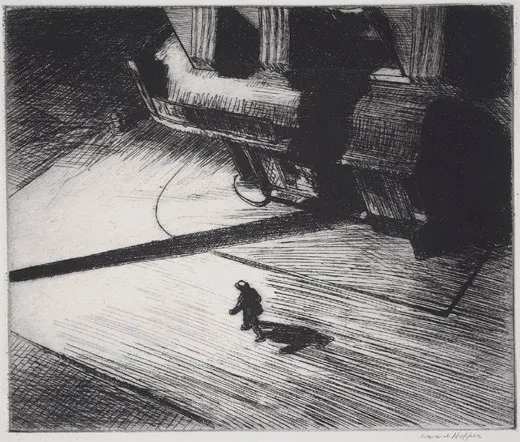

Hopper sold one painting in 1913 but didn't make another major sale for a decade. To support himself, he continued to illustrate business and trade journals, assignments he mostly detested. In 1915 he took up printmaking as a way to remain engaged as an artist. His etchings and drypoints found greater acceptance than his paintings; and at $10 to $20 each, they occasionally sold. Along with the bridges, buildings, trains and elevated railroads that already were familiar elements in his work, the prints feature a bold development: Hopper began portraying women as part of the passing scene and as the focus of male longing. The etching Night on the El Train is a snapshot of a pair of lovers oblivious to everyone else. In Evening Wind, a curvaceous nude climbs onto a bed on whose other side the artist seems to be sitting as he scratches a lovely chiaroscuro moment into a metal plate. In these etchings, New York is a nexus of romantic possibilities, overflowing with fantasies tantalizingly on the brink of fulfillment.

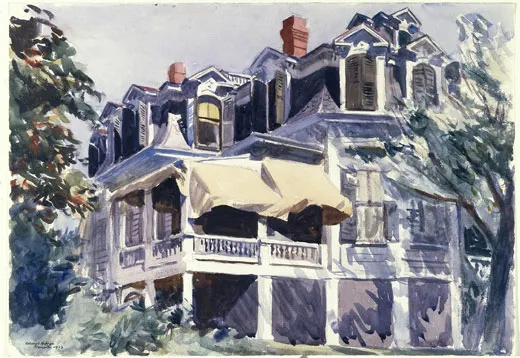

Between 1923 and 1928, Hopper often spent time during the summer in Gloucester, Massachusetts, a fishing village and art colony on Cape Ann. There he devoted himself to watercolor, a less cumbersome medium that allowed him to work outdoors, painting humble shacks as well as the grand mansions built by merchants and sea captains. The watercolors marked the beginning of Hopper's real professional recognition. He entered six of them in a show at the Brooklyn Museum in November 1923. The museum bought one, The Mansard Roof, a view of an 1873 house that showcases not only the structure's solidity, but the light, air and breeze playing over the building. A year later, Hopper sent a fresh batch of Gloucester watercolors to New York dealer Frank Rehn, whose Fifth Avenue gallery was devoted to prominent American painters. After Rehn mounted a Hopper watercolor show in October 1924 that was a critical and financial smash, the artist quit all commercial work and lived by his art for the rest of his life.

Hopper's career as a watercolorist had been jump-started by the encouragement of Josephine Verstille Nivison, an artist whom Hopper had first courted in 1923 in Gloucester. The two wed in July 1924. As both were over 40, with established living habits, adjusting to each other took some effort. Their marriage was close—Josephine moved into her husband's Washington Square quarters and did not have a separate work space for many years—and turbulent, for they were physical and temperamental opposites. Towering over her, he was stiff-necked and slow-moving; she was small, snappy and birdlike, quick to act and quicker to speak, which some said was constantly. Accounts of Jo Hopper's chattering are legion, but her vivacity and conversational ease must have charmed her future husband, at least initially, for these were traits he lacked. "Sometimes talking with Eddie is just like dropping a stone in a well," Jo quipped, "except that it doesn't thump when it hits bottom." As time passed, he tended to disregard her; she resented him. But Hopper probably could not have tolerated a more conventional wife. "Marriage is difficult," Jo told a friend. "But the thing has to be gone through." To which Hopper retorted, "Living with one woman is like living with two or three tigers." Jo kept her husband's art ledgers, guarded against too many guests, put up with his creative dry spells and put her own life on hold when he roused himself into working. She posed for nearly every female figure in his canvases, both for his convenience and her peace of mind. They formed a bond that only Edward's death, at age 84, in 1967 would break. Jo survived him by just ten months, dying 12 days before her 85th birthday.

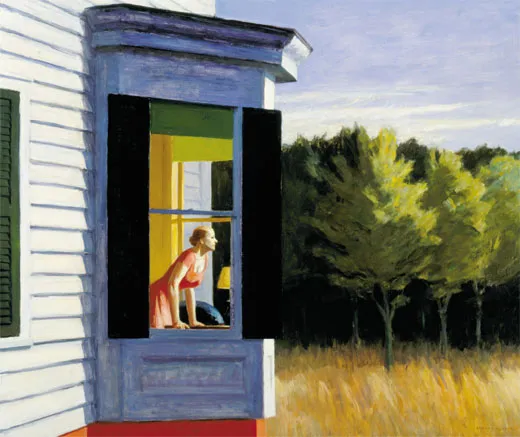

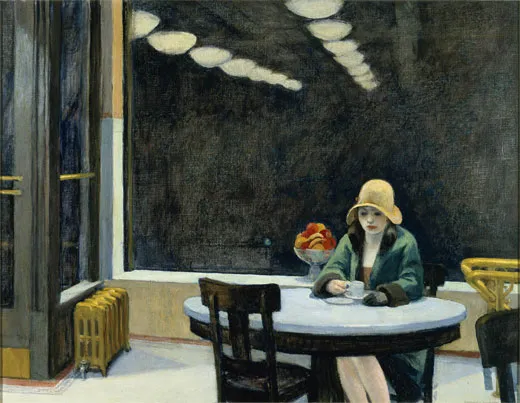

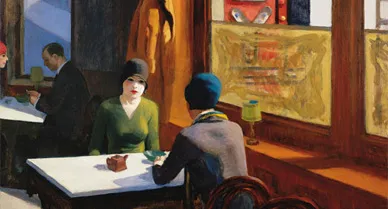

Jo Hopper's availability as a model likely spurred her husband toward some of the more contemporary scenes of women and couples that became prominent in his oils of the mid- and late 1920s and gave several of them a Jazz Age edge. In Automat and Chop Suey, smartly clothed independent women, symbols of the flapper era, animate a heady cosmopolitan milieu. Chop Suey had an especially personal meaning for the Hoppers—the scene and the place derive from a Columbus Circle Chinese restaurant where they often ate during their courtship.

Hopper ignored much of the city's hurly-burly; he avoided its tourist attractions and landmarks, including the skyscraper, in favor of the homely chimney pots rising on the roofs of commonplace houses and industrial lofts. He painted a number of New York's bridges, though not the most famous, the Brooklyn Bridge. He reserved his greatest affection for unexceptional 19th- and early 20th-century structures. Echoing his Gloucester watercolors (and decades ahead of the historic preservation movement), he treasured vernacular buildings, drawing satisfaction from things that stayed as they were.

By the late 1920s, Hopper was in full command of a powerful urban vision. He had completed several extraordinary paintings that seemed almost carved out of the materials they were depicting, brick by brick and rivet by rivet. Manhattan Bridge Loop (1928) and Early Sunday Morning (1930) match the monumental scale of New York itself, whereas Night Windows (1928) acknowledges in an almost cinematic way the strange nonchalance that results from lives lived in such close proximity: even when you think you are alone, you are observed—and accept the fact. The unsettling nature of Night Windows derives from the position of the viewer—directly across from a half-dressed woman's derrière. The painting suggests that Hopper may have affected movies as much as they affected him. When German director Wim Wenders, a Hopper fan, was asked why the artist appeals to so many filmmakers, he said: "You can always tell where the camera is."

With the creation of such distinctive paintings, Hopper's reputation soared. Two on the Aisle sold in 1927 for $1,500, and Manhattan Bridge Loop brought $2,500 in 1928. That same year, Frank Rehn took in more than $8,000 for Hopper's oils and watercolors, which yielded the artist about $5,300 (more than $64,000 today). In January 1930, House by the Railroad became the first painting by any artist to enter the permanent collection of New York's newly established Museum of Modern Art. Later that year, the Whitney Museum of American Art bought Early Sunday Morning for $2,000; it would become a cornerstone of that new institution's permanent collection. The august Metropolitan Museum of Art purchased Tables for Ladies for $4,500 in 1931, and in November 1933, the Museum of Modern Art gave Hopper a retrospective exhibition, an honor rarely bestowed on living American artists. He was 51.

Since 1930, the Hoppers had spent summer vacations in South Truro, Massachusetts, near the tip of Cape Cod. A small town situated between Wellfleet and Provincetown, Truro had kept its local character. In 1933 Jo received an inheritance, which the couple used to build a house there; it was completed the next year. The Hoppers would spend nearly every summer and early autumn in Truro for the remainder of their lives.

By the end of the 1930s, Hopper had changed his working methods. More and more, instead of painting outside, he stayed in his studio and relied on synthesizing remembered images. He pieced together Cape Cod Evening (1939) from sketches and recollected impressions of the Truro vicinity—a nearby grove of locust trees, the doorway of a house miles away, figures done from imagination, dry grass growing outside his studio. In the painting, a man and woman seem separated by their own introspection. Hopper's "equivocal human figures engaged in uncertain relationships mark his paintings as modern" as strongly as his gas pumps and telephone poles, writes art historian Ellen E. Roberts in the current show's catalog.

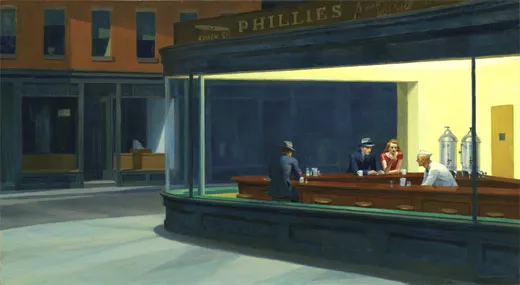

The notions of disconnection and inaccessiblity are most fully realized in Nighthawks (1942), Hopper's most famous painting. Like the Mona Lisa or Whistler's Mother or American Gothic, it has taken on a life of its own in popular culture, with its film-noir sensibility sparking scores of parodies. The figures, customers at a late-night eatery, flooded by an eerie greenish light, look like specimens preserved in a jar. Hopper has banished every superfluous detail: the huge plate-glass window is seamless, and there is no visible entrance to the restaurant. Like characters in a crime movie or existential novel, the figures seem trapped in a world that offers no escape.

As Hopper aged, he found it increasingly difficult to work, and as his output decreased in the late 1940s, some critics labeled him as passé. But younger artists knew better. Richard Diebenkorn, Ed Ruscha, George Segal, Roy Lichtenstein and Eric Fischl appropriated Hopper's world and made it their own. Eight decades after his most evocative canvases were painted, those silent spaces and uneasy encounters still touch us where we are most vulnerable. Edward Hopper, matchless at capturing the play of light, continues to cast a very long shadow.

Avis Berman is the author of Edward Hopper's New York and the editor of My Love Affair with Modern Art: Behind the Scenes with a Legendary Curator by Katharine Kuh (2006).

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4a/00/4a00d556-4e27-4a78-a25f-3d59c1b22f90/hopper-selfjpg__600x0_q85_upscale.jpg)