Homemade Clothes for Hollywood - Made Movies

Rabbit Goody has been the go-to weaver for historically accurate fabric for the movie industry’s biggest period dramas

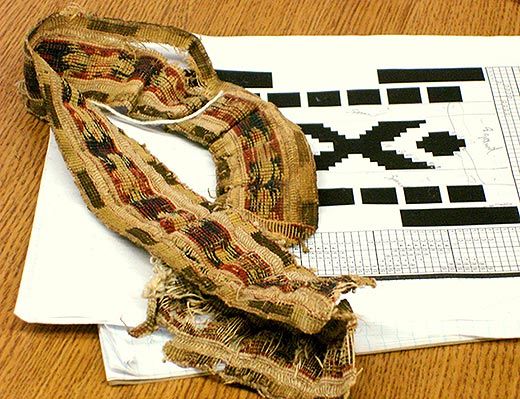

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Carriage-lace-631.jpg)

A modest low-slung metal building, set in the woods off a dirt road, is home to the world-famous Thistle Hill Weavers, workplace and studio of textile historian and weaver Rabbit Goody. Approaching the building a muffled thwack-thwack-thwack mechanical sound created by power looms can be heard. When the door is opened, the noise spills out along with the smell of fibers mixed with machine oil.

Goody has been involved in movies for nearly 15 years. Since her start with the movie adaptation of The Scarlet Letter (1995), starring Demi Moore, Thistle Hill Weavers has worked on dozens of films. The studio has created historically accurate fabric for a number of iconic costumes, from Tom Hanks’ Depression-era overcoat in Road to Perdition to Daniel Day Lewis’ oil man outfit in There Will Be Blood to many of the costumes in HBO‘s John Adams. Goody understands how costume designers place great importance on the most miniscule details and knows how to get them right.

Costume designer Kimberly Adams worked with Thistle Hill on a number of projects including The Chronicles of Narnia and There Will Be Blood. “As a designer, you always want to sell the time period with fabrics and shapes that are true to the period in order to bring the audience into the real world of the story,” says Adams.

“Today’s fabrics often don’t work in other time periods,” Adams explains. “The weights, textures and content are quite different, and these factors really do make a difference in making a costume look true to a time period.”

Considering her Hollywood-based clientele, upstate New York seems an unlikely setting for Goody’s textile mill. She landed in the Cherry Valley area in the 1970s as part of the counter-culture movement, and she never left. (Allen Ginsberg had a farm down the road as did a number of other poets, artists and musicians.) Although she came to the area to farm – even today she notes “weaving is my trade but my lifestyle is agricultural” – she soon established herself as an accomplished hand weaver. Before setting up Thistle Hill, she worked for the New York State Historical Association in the nearby Farmer’s Museum, located in Cooperstown.

Over the years she amassed an encyclopedic knowledge of American textiles and weaving technology, which has made her indispensible to the film industry and historic properties that are looking for historically accurate reproductions of clothing, bed hangings, window treatments and carpet.

Goody got her first movie job when the costume designer from The Scarlet Letter saw the textile work she did for Plimoth Plantation, a museum and educational center in Plymouth, Massachusetts, that recreates 17th-century America. The film needed clothing and interior furnishing fabrics accurate to that same time period from Nathaniel Hawthorne's novel.

“The camera eye is better than any human eye so inaccuracies show up glaringly,” explains Goody. “The minute anyone sees an inaccuracy in a movie, that picture is trashed – if you don’t believe one part of it, you’re not going to believe any part of it. A lay person may not know what would be appropriate for 17th-century fabric, but it will register that something is wrong.”

When a designer contacts them, Rabbit and Jill Maney, Thistle Hill’s office manager, who also has a PhD in early American history, research everything they can about the movie – time period, characters, basic plot and what color schemes the costume designers will use. Then they send the designer an enormous packet of textile samples. From there it becomes a collaborative process. The designers determine what they like and don’t like (need it rougher, smoother, more texture, less texture) and if they like something, Goody asks what it is about the fabric that appeals to them.

“Costume designers for the most part do not speak ‘cloth,’” says Goody. “They do by the end, though.” Rabbit has found that designers pay a surprising amount of attention to detail. Drape, weight, texture, how a fabric moves, how it reflects color, or how it works with somebody’s coloring, for example, are all important to them.

Accurate fiber content is not as important to movies as it is for a historic house or museum looking for a historic reproduction. But Thistle Hill always uses natural fibers when creating movie textiles, so that the fabric can be dyed and aged by the costumers.

“Sometimes we hardly recognize our fabrics because they’ve been so aged,” says Maney. “For [the 2007 film] No Country for Old Men we made plaid cowboy shirts from the 1970s – doesn’t sound like a project for us – but the designer found a shirt she liked but couldn’t find enough of them so we provided yardage. Then the shirts had be aged in all different ways – sun-faded, torn, tattered, and soiled – and that’s the kind of detail that makes the movie believable.”

Six weavers work at Thistle Hill although Goody is the only one who does the design work. Everyone performs multiple tasks, from running power looms to spinning thread to making trim. Rabbit’s power looms are all at least 100 years old – there are a couple of nonworking looms sitting out behind the mill that are cannibalized for parts when the old looms break down.

The bulk of the mill is one big room with weavers either setting up or running huge looms. The noise is so deafening the weavers wear ear protectors. Everywhere you look big metal machines are creating gorgeous lengths of fabric, including striped Venetian carpet and white cotton dimity and soft, cream-colored cloth from Peruvian alpaca thread. One weaver sits at a bench before a loom pulling 3,300 threads through heddles – they keep the warp threads separate from each other. She then threads them through the sley, which resembles the teeth of a giant comb. The entire painstaking process takes her three days to complete.

Leftover yardage from past projects sits in an adjacent fitting room. Thistle Hill mixes in movie work with weaving for museums and historic houses so Goody can point to fabric used for George Washington’s bed at his historic headquarters in Newburgh, New York, as well as Brad Pitt’s trousers from The Curious Case of Benjamin Button.

Clothing for John Adams and the other founding fathers kept Goody and her weavers busy for half a year. “Thistle Hill wove such beautiful fabrics,” remembers Michael Sharpe, first assistant costume designer for the miniseries. “They recreated fabrics that would have been ‘homespun’ by settlers in the New World. Thistle Hill fabrics allowed us to set the tone of ‘America’s’ fibers versus that of the fine English and French silks and woolens.”

Sharpe liked the fabric so much that as Maney sent him boxes of period-appropriate textiles from the finishing room, he kept wanting more. “I was frequently asked by our costume makers in the United States, London, Canada and Hungary where we’d found such incredible fabrics,” says Sharpe. “I happily replied – ‘We made them!’”