Heaven Scent

A 600-year-old pharmacy started by Florentine monks is now a trendy global marketer of perfumes and medieval elixirs

Among Florence's churches, Santa Maria Novella is often overlooked: it lacks the grandeur of the Duomo and the poignancy of Santa Croce, where Michelangelo and Galileo are entombed. And while its Renaissance frescoes may rival those of San Marco, its location in a seedy neighborhood near the city's main train station keeps it off the radar of many visitors to the City of Lilies.

But as home to one of the world's oldest pharmacies, Santa Maria Novella boasts an attraction no other church in Italy can match. Dominican monks began concocting herbal remedies here in the 13th century, in the time of Giotto and Dante. Today, the Officina Profumo-Farmaceutica di Santa Maria Novella still sells traditional elixirs, along with more contemporary skin-care products, oils and perfumes.

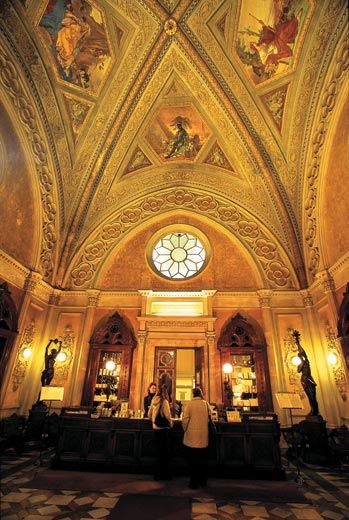

From the outside, the church offers little sign of the aromatic riches within. But around the corner from its main entrance, an enormous wooden door opens into another world, where the strong, sweet fragrance of flowers and essential oils wafts through the pharmacy's historic rooms. The monks' simple apparatus for distilling flower water rests inside wooden cabinets, flanked by old containers used for lotions and potions, lists of ingredients and even the monks' original recipe ledgers. Merchandise lines the walls of the dimly lit, frescoed rooms—all manner of soaps, sachets and scents, many made according to ancient formulas.

The Dominicans, an order devoted to poverty and charity, first arrived in Florence in 1219, in the last years of Saint Dominic, who would die in Bologna in 1221. His followers took over a church, then called Santa Maria delle Vigne, and began the process of transforming it into a monastery. At the time, the Dominicans were engaged in fierce competition with the Franciscans for the loyalty of medieval Florentines in what would soon become one of Europe's wealthiest and most powerful cities. Their cause was helped by a Verona-born Dominican, later known as Saint Peter the Martyr, who attracted huge crowds to his sermons at Santa Maria Novella, as Santa Maria delle Vigne had come to be known.

By 1381, the Dominicans were operating an infirmary there, with herbal remedies made by the monks themselves. Among the first distillates was rose water, a simple essence prescribed as an antiseptic to clean houses after an outbreak of plague. (It remains on the pharmacy's shelves today, although it's now more likely to be used for perfume or aromatherapy.)

Also among the early creations were tonics reflecting the sensibility of the times: the imaginatively named "Vinegar of the Seven Thieves," for example, was a popular remedy for women suffering from "fainting fits." The vinegar is still available for those in need of a quick pick-me-up. Also available to Florentine ladies was a concoction designed to calm "hysterical women." It, too, is still on the shelves, bearing the innocuous name Santa Maria Novella Water—now recommended for its "antispasmodic properties."

By the late 15th century, Florence was plunged into turmoil, with political attacks on the Medici dynasty spurred by the fiery preaching of the Dominican monk Savonarola—who denounced all vice and exhorted the citizens of Florence to burn their finery in a "bonfire of vanities." The pharmacy's nostrums, however, were mostly medicinal, and the monks quietly labored on. By the mid-16th century, relative calm had returned to the city under the rule of Cosimo de' Medici.

By then the monastery's pharmaceutical activities were being run as a separate business, managed by a layman and, it appears, were profitable. One entry in church records reports a large investment in vases, stoppers and pestles. The operation's manufacture of perfumes was apparently key to winning the allegiance of its most famous customer, Catherine de' Medici.

She had been born in Florence in 1519, and at age 14 famously became the bride of Henry, Duke of Orleans, the future king of France. She proved a legendary figure both for her political intrigues and her love of novelty: she is credited with promoting, in the French Court, innovations ranging from the sidesaddle to the handkerchief—even tobacco. The pharmacy created a new fragrance for her, a perfume that became known as acqua della regina, or "water of the queen." In due course, Catherine's patronage proved the making of the place.

The growth of the business was not welcomed by all; unease among some monks that the sweet smell of success might distract from the Christian pieties led to a temporary shutdown of the production of medicines in the early 1600s. But manufacture resumed in 1612, for a run of two and a half centuries. In 1866 the Italian state confiscated all church property. The move could have been the pharmacy's death knell but for the vision of the last monk to act as its director, Damiano Beni. In a deft move, he handed over control of the enterprise to his layman nephew, who eventually bought it from the state. His descendants remain involved in the business today.

As a secular endeavor, the pharmacy could fully exploit the trends of the times. In the 1700s, it had expanded its product line from distilling medicines and perfumes to manufacturing alcohol. In the 19th century, as alcohol-laden patent medicines and tonics became all the rage in the United States, the pharmacy's liqueur, Alkermes—advertised as a way to "revive weary and lazy spirits"—became a top seller.

Today the pharmacy still occupies its historic quarters, but it has expanded into an international concern, with stores in New York, Los Angeles and Tokyo. Eight years ago it opened a small factory two miles away, where the monks' ancient techniques have been streamlined, but where much of the manufacturing continues to be done by hand. The factory can turn out 500 bars of soap a day in any one of 25 varieties; each bar is then aged for a month before being chiseled by hand into its final shape.

For those who fancy themselves a modern-day Catherine de' Medici, the pharmacy produces a fragrance similar to the "water of the queen," although it now goes by the less regal name of Eau de Cologne Classica. Some 40 colognes, in fact, are offered, catering to a huge range of tastes. The current managing director, an urbane Florentine named Eugenio Alphandery, has expanded his clientele still further with a new fragrance, Nostalgia, based on his own passion—fast cars. A whiff of the cologne evokes nothing so much as leather seats, tires on a track and a hint of gasoline fumes.

Catherine de' Medici, where art thou?

Mishal Husain is an anchor for BBC World and lives in London.

Scott S. Warren works out of Durango, Colorado.