Gaudí’s Gift

In Barcelona, a yearlong celebration spotlights architecture’s playful genius the audacious and eccentric Antoni Gaudí

When I first came upon the startling and fanciful works of Antoni Gaudí a quarter of a century ago, I assumed he must have been some kind of freakish genius who created wonderful art out of his wild imagination, without regard to other architects or any artist before or during his time. I also thought that the Barcelona architect now being honored by that city’s “International Gaudi Year” celebrations was one of a kind, and that his fantastic curving structures, shattered-tile chimneys, lavish decoration and bizarre towers stood alone.

I soon found, however, that this assumption troubled my Barcelona friends. To them, Gaudi was deeply rooted in the history of Catalonia, their region of Spain, and in the fashion of Art Nouveau that stirred such centers of culture as Paris, Vienna, Brussels, Glasgow, Munich and Barcelona at the turn of the 20th century. I was making the common error of an outsider encountering the greatness of Gaudi for the first time.

This was driven home to me one evening by Miquel de Moragas, a professor of communications at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, who took me on a breakneck tour of the city. Knowing of my interest in Gaudi, Moragas, the enthusiastic, fast talking son of a distinguished Barcelona architect, whipped his Renault in and out of honking traffic, slammed to a sudden stop at street corners, pointed to elaborately curved and decorated buildings, and shouted above the din each time, “Modernismo.” That is the Spanish term denoting the Art Nouveau era in Barcelona.

The 15 or so buildings selected by Moragas were all Gaudi-like, but none were by Gaudi. Moragas was not trying to downgrade Gaudi. He looks on him as a colossus of Catalonia, one of the great cultural gifts of Barcelona to the world. He believes that Gaudi’s originality put him steps ahead of his main rivals in architectural Art Nouveau in Barcelona. But, as Moragas emphasized, “Gaudi was not alone.”

It is a truth worth keeping in mind as Barcelona commemorates the 150th anniversary of the architect’s birth this year. The extraordinary attention may entice visitors into making my mistake. But Gaudi is best understood by placing him in the artistic, social and political context of his time and city.

Barcelona, the capital of Catalonia (the northeastern region of Spain, which was an independent state until the 15th century) and the center of Catalan culture, needs no Gaudi celebration to attract tourists. In 2001, some 3.4 million of them (more than twice the city’s population) came to the Mediterranean metropolis, many of them lured by Gaudi. Year-round, crowds gape at the grand twists of his imagination: the soaring towers of the Sagrada Familia, the huge, awe-inspiring church still under construction; the breathtaking, undulating facade of La Pedrera, the apartment building, also called Casa Mila, that hovers over the fashionable Passeig de Gracia boulevard; and the gigantic mosaic lizard that guards the playful Park Guell on the outskirts of Barcelona. In fact, Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia, the most popular tourist site in the city, has become its symbol, nearly as emblematic as the EiffelTower or the Statue of Liberty. The facade and towers of this uncompleted church adorn Tshirts, scarves, platters, posters, mousepads, guidebooks and postcards galore.

Barcelona officials say they want the commemorative year to deepen the Gaudi experience. “We have to lift Gaudi off the postcards,” says Daniel Giralt-Miracle, the art critic who directs the government team that organized the celebration. “We must go on to really see Gaudi, to know and understand him. That is the big objective of the Gaudi year.”

In line with this, museums and other institutions have mounted some 50 exhibitions to explain Gaudi’s architectural techniques, showcase his furniture and interior design, and describe his era. Government-sponsored buses shuttle tourists among the main Gaudi sites and exhibitions. And the doors of some buildings, like the dramatic Casa Batllo, an imposing residence two blocks down the boulevard from La Pedrera, have been opened to the public for the first time.

As I learned, Gaudi is not easy. Both his art and personality are complex. To start with, he was obsessed with nature and geometry. Nature, he insisted, was “the Great Book, always open, that we should force ourselves to read.” He embellished his edifices with replicas of soaring trees, multicolored lizards and fossilized bones, and he fitted his structures with architectural paraboloids and other intricate geometric forms. He didn’t like to work from architectural plans, for he found his visions hard to put down on paper. Then, too, he often changed his designs as his buildings came alive.

His manner was brusque and sometimes overbearing. He made it clear to others that he never doubted his creative genius. He did not like assistants to question his work. “The man in charge should never enter into discussions,” he once said, “because he loses authority by debate.” Rafael Puget, a contemporary of Gaudi’s who knew him well, described the architect as a man with “a morbid, insoluble pride and vanity” who acted “as though architecture itself had begun at the precise moment when he made his appearance on earth.” He grew intensely religious as he aged, and he devoted the last decade of his life to construction of the hugely ambitious Sagrada Familia. But critics charged that he was driven more by his ego than his devotion to God.

Antoni Gaudí I Cornet was born June 25, 1852, in the small Catalan town of Reus, 75 miles southwest of Barcelona. He came from a long line of artisans; his father, grandfather and greatgrandfather were all coppersmiths. He learned the elementary skills of the copper craft as a youngster, then left for Barcelona in 1868 at age 16 to complete his secondary education and enroll in the school of architecture at the university there.

His early coppersmith training may account for his enthusiasm for the nitty- gritty of building. He would become a hands-on architect, working alongside his craftsmen. When La Pedrera was being built, for example, he stood in the street and personally supervised the placement of the stone slabs of the facade, ordering the masons to make adjustments until he found the proper place for each slab.

His student work did not please all of his professors. While working parttime in architectural studios, he often skipped classes and made it clear to students and teachers alike that he did not think much of architectural education. In his view, it was mere discipline, bereft of creativity. The faculty vote to pass him was close, and at his graduation in 1878, the director of the school announced, “Gentlemen, we are here today either in the presence of a genius or a madman.”

Judging by photographs, Gaudi was a handsome young man with penetrating blue eyes, reddish hair and a thick beard. He wore well-cut, fashionable suits, attended opera at the famous Liceo theater and enjoyed dining out.

Gaudi was the youngest of five children, and all the others died before him, two in childhood, two as young adults. He lost his mother in 1876, when he was 24, just two months after the death of his brother, Francesc, a medical student. His sister Rosa died three years later, leaving a child, Rosita, whom Gaudi and his father brought up. Tubercular and alcoholic, she, too, died as a young adult.

Gaudi never married. While designing housing for a workers’ cooperative early in his career, he fell in love with Pepeta Moreu, a divorced schoolteacher and rare beauty who demonstrated her independence by swimming in public, reading republican newspapers and associating with socialists and antimonarchists. Gaudi asked her to marry him, but she turned him down. Biographers mention a possible interest in two or three other women during his lifetime but offer no details. His niece, Rosita, however, was definitive. “He didn’t have a girlfriend or amorous relations,” she once said. “He didn’t even look at women.”

The Barcelona of the 1880s was an exciting place for a young architect. The city was expanding rapidly, with new homes and offices to be built. Rich bourgeoisie were able to spend lavishly on construction. They wanted to look modern and trendsetting and were open to new artistic fashions. Three architects would benefit most from this patronage: Lluis Domenech i Montaner, who was three years older than Gaudi, Josep Puig i Cadafalch, who was 15 years younger, and, of course, Gaudi himself.

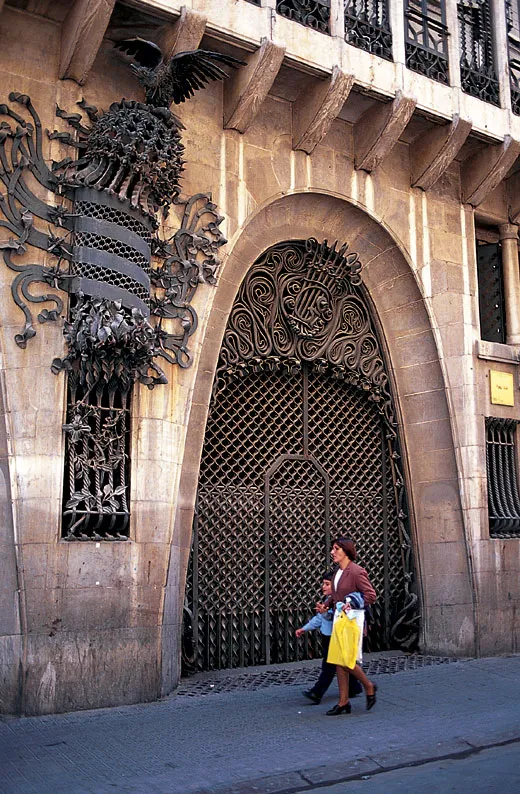

The course of Gaudi’s career was set when, at age 26, he met Eusebi Guell, a wealthy industrialist, politician and future count. Only five years older than Gaudi, Guell asked him in 1883 to design a gate, stables, hunting pavilion and other small structures for his family’s estate on the periphery of Barcelona. For the next 35 years, the rest of Guell’s life, he employed Gaudi as his personal architect, commissioning a host of projects, from mundane laundry facilities to the elegant and stately Palau Guell, his mansion just off La Rambla, the mile-long esplanade that runs through the heart of the old city. At his patron’s behest, Gaudi even designed a crypt. For it, he devised an ingenious system of inverted modeling for calculating loads on columns, arches and vaults using strings, from which he hung bags of bird shot as weights.

Guell was a munificent patron. While Gaudi was building the Palau in the late 1880s, the skyrocketing construction costs alarmed one of the industrialist’s secretaries, a poet named Ramon Pico Campamar. “I fill Don Eusebi’s pockets and Gaudi then empties them,” Pico complained. Later, he showed a pile of bills to his employer. After looking them over, Guell shrugged. “Is that all he spent?” he said.

In 1883, the year he started to work for Guell, Gaudi won a contract to take over as architect of the ExpiatoryTemple of the Holy Family, the Sagrada Familia. The project was supported by a group of conservative Catholics who wanted a holy edifice where sinners could atone for succumbing to modern temptations.

Although Gaudi had not been especially devout as a young man, construction of the Sagrada Familia deepened his faith. The Lenten fast he went on in 1894 was so strict it almost killed him. Father Josep Torras, spiritual adviser to the Artistic Circle of Saint Luke, an organization of Catholic artists to which Gaudi belonged, had to talk him into breaking it.

At the turn of the 20th century, fervent religious belief often went hand in hand with intense Catalan nationalism. Chafing at domination by Madrid, Catalans began to dwell on their history as an independent Mediterranean power. This led to a revival of Catalan cultural traditions, a determination to use the Catalan language and demands for political autonomy. Though a committed Catalan nationalist, Gaudi did not take part in politics. Still, when Alfonso XIII, the Spanish king, visited the site of the Sagrada Familia, Gaudi would speak to him only in Catalan. Years later, police stopped the 72-yearold architect as he tried to attend a prohibited Mass for 18th-century Catalan martyrs. When the police demanded that he address them in Castilian Spanish, the official language, he retorted, “My profession obliges me to pay my taxes, and I pay them, but not to stop speaking my own language.” Gaudi was thrown in a cell and released only after a priest paid his fine.

Gaudi’s work, like that of Domenech and Puig, owed much to the ornamental Art Nouveau style emerging in other European cities. In addition to twisting curves and structures that imitated natural forms, he favored Arabic and Oriental designs and symbols that encouraged nationalist feelings. If you look at the ironwork and furniture designed by Gaudi and that of the French Art Nouveau architect Hector Guimard, it is hard to tell them apart. Yet Gaudi did not regard himself as a disciple of modernismo, and considered the artists who gathered evenings at Els Quatre Gats (a cafe designed by Puig) to discuss their work as too libertine. He preferred the company of fellow members of the conservative and religious Artistic Circle of Saint Luke.

Much of Gaudi’s early architecture, including the Palau Guell, strikes me as dense and dark—though lightened by novel touches. Reviving an old technique of the Arabs of Spain, he sheathed the palace’s 20 chimneys with fragments of ceramics and glass. Under his direction, workmen would smash tiles, bottles and dishes and then fit the pieces into bright, abstract patterns. He apparently even smashed up one of Guell’s Limoges dinner sets. For Gaudi, the myriad colors resulting from this technique, known as trencadis, reflected the natural world. “Nature does not present us with any object in monochrome . . . not in vegetation, not in geology, not in topography, not in the animal kingdom,” he wrote in his 20s. Trencadis became a Gaudi trademark.

One project, the Park Guell, is a paradise of trencadis. At the turn of the 20th century, Guell decided to create a suburban garden city on a hill overlooking Barcelona. The project never fully materialized; only two homes were built, including one that Gaudi moved into with his father and niece. But the architect completed most of the public works for the aborted garden city and brightened them with fragmented tile. With its mushroomlike spires, grand serpentine bench, fanciful fountain, impish air and vistas of the city, the Park Guell remains a popular place to take children on weekends.

Gaudi created several buildings elsewhere in Spain, and there were stories that he once drew up plans for a hotel in New York. But his greatest work was largely confined to Barcelona and its suburbs. Three buildings there, all works of his maturity—the Casa Batllo, La Pedrera and the Sagrada Familia—illustrate the essence of his architecture. When American architect Louis Sullivan saw photographs of the Sagrada Familia, he described it as “the greatest work of all creative architecture in the last 25 years.” Gaudi conceived his buildings as works of art. He intended La Pedrera, for example, to serve not only as an apartment building but also as the pedestal for an immense statue of the Virgin Mary, until the owner balked. So Gaudi turned the entire edifice into a monumental sculpture. (After decades of functional, nondecorative design, Gaudi’s architecture-as-art approach is back in vogue, carried out by such contemporary architects as deconstructivists Frank Gehry and Daniel Libeskind. As high-tech architect Norman Foster put it a few years ago, “Gaudi’s methods, one century on, continue to be revolutionary.”)

Completed in 1906, Casa Batllo was Gaudi’s reconstruction of an apartment building on a block that already had works by Domenech and Puig. Although all three structures are outstanding examples of modernismo, the street is sometimes called “The Block of Discord” because it displays rival efforts. Gaudi stretched fantasy far more than the others, with a facade of oddshaped windows separated by columns that resemble petrified bones.

The success of Casa Batllo prompted wealthy developers Pere and Roser Mila to commission Gaudi to build a luxury apartment house just a few blocks away. Gaudi’s Casa Mila, or, as it became known, La Pedrera, the Stone Quarry, is an enormous building with honey-colored limestone slabs curving across the facade, sculpted balconies railed in thick cast-iron vegetation, and a rooftop guarded by strange, warriorlike chimneys and vents.

Though it has long been hailed as an Art Nouveau masterpiece, La Pedrera provoked ridicule when first completed in 1910. Cartoonists portrayed it as a garage for dirigibles, a war machine with cannon protruding from every window and a warren of caves infested with animals. Painter Santiago Rusinyol joked that the only pet a tenant could possibly keep there was a snake. There was also some praise: critic Ramiro de Maeztu, for instance, wrote in the newspaper Nuevo Mundo that “the man’s talent is so dazzling that even the blind would recognize Gaudi’s work by touching it.” But, all in all, Barcelona, like cities elsewhere in Europe, was losing its taste for Art Nouveau architecture.

Gaudi, who was 58 when La Pedrera was completed, would not receive another major private commission from anyone but Guell for the rest of his life. Turning his attention to the Sagrada Familia, he designed for it crusty stone and ceramic spires that soar like primeval trees. He planned two grand portals with sculpture as elaborate as any of that in the great Gothic cathedrals of Europe.

But donations for the church dwindled in the early 20th century, as Barcelona’s citizens became disenchanted with the radical conservatism espoused by the Sagrada Familia’s main backers. Gaudi sold his house in order to raise money for the project and solicited others for funds, even going so far as begging in the streets. His father died in 1906, his niece in 1912, leaving him with no immediate family. His spiritual adviser, Bishop Torras, and his patron, Guell, died a few years later. “My best friends are all dead,” Gaudi, then 64, said after Guell’s death in 1918. “I have no family, no clients, no fortune, nothing.” But he was not despairing. “Now I can devote myself entirely to the temple,” he declared.

By now he was nearly bald, his beard was white and he appeared too thin for his unkempt, soiled clothes. He wore bandages on his legs to ease arthritic pain, walked with a stick and laced his shoes with elastic. He lunched on lettuce leaves, milk and nuts, and munched on oranges and bread crusts he kept in his pockets. In 1925 he moved into a small room alongside his studio workshop in the Sagrada Familia so he could be closer to his allconsuming project.

On June 7, 1926, crossing the Gran Via boulevard, Antoni Gaudi looked neither right nor left, ignored warning shouts and the clanging bell of an onrushing trolley, and crumpled as it struck him down. He had no identification and looked so disreputable he was taken to the public ward of a Barcelona hospital. When he was identified a day later, he refused suggestions that he move to a private clinic. “My place is here, among the poor,” he reportedly said. He died a couple of days later, just two weeks shy of his 74th birthday, and was buried in the crypt of the Sagrada Familia.

Work on the church continued sporadically after his death. By the time the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War halted construction in 1936, four spires stood in place. Catalan republicans, angered by the Catholic church’s support of fascist rebel leader Generalissimo Francisco Franco, ravaged the churches of Barcelona. They sacked Gaudi’s old office in the Sagrada Familia and destroyed his drawings, but left the structure intact. British writer George Orwell, who fought with the anti-Franco forces, called it “one of the most hideous buildings in the world.” The leftists, he contended, “showed bad taste in not blowing it up when they had the chance.”

Although Gaudi’s admirers included the likes of Catalan Surrealist painter Salvador Dali, the 100th anniversary of his birth passed in 1952 without elaborate commemorations. Praise from the eccentric Dali, in fact, only made Gaudi seem outlandish and isolated—a strange hermit who relied on wild dreams for inspiration. But Gaudi, as Time art critic Robert Hughes wrote in his book Barcelona, did not believe “his work had the smallest connection with dreams. It was based on structural laws, craft traditions, deep experience of nature, piety, and sacrifice.” Thoughtful interest in Gaudi has swelled over the past few decades as Spanish critics, like critics elsewhere, began to look more closely at neglected works from the Art Nouveau era.

In 1986, a Barcelona-based savings bank, the Caixa Catalunya, purchased La Pedrera. The structure, which along with Gaudi’s Palau Guell and Park Guell was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1984, was in woeful disrepair, but a foundation formed by the bank meticulously restored it and opened parts of it to the public in 1996. Foundation director J. L. Gimenez Frontin says, “We had to look for the same earth to make the same bricks.”

The bank allows visitors access to the roof and two permanent exhibitions. One traces Gaudi’s life and work; the second presents an apartment as it might have been furnished at the turn of the century. In honor of International Gaudi Year, a special exhibition, “Gaudi: Art and Design,” featuring furniture, doors, windows, doorknobs and other decorative elements designed by the architect, is on view through September 23.

In the early 1980s, work resumed in earnest on the Sagrada Familia. The nave is scheduled to be ready for worship by 2007, but the full church, with a dozen spires, may take until mid-century to complete. Critics complain that contemporary artists, operating without Gaudi’s plans and drawings, are producing ugly and incompatible work. Robert Hughes calls the post-Gaudi construction and decoration “rampant kitsch.”

For its part, the Catholic Church wants to make Gaudi a saint. The Vatican authorized the start of the beatification process in 2000 after Cardinal Ricard Maria Carles of Barcelona requested it, proclaiming that Gaudi could not have created his architecture “without a profound and habitual contemplation of the mysteries of the faith.” But that, contend some critics, is going too far. Says professor of communications Miquel de Moragas: “We think of him as Gaudi the engineer, Gaudi the architect, Gaudi the artist, not Gaudi the saint.”

But whether Gaudi is a saint or not, there is no doubt about the power of his architecture to excite wonder and awe. As Joaquim Torres-Garcia, an artist who worked at the same time as Gaudi, put it, “It is impossible to deny that he was an extraordinary man, a real creative genius. . . . He belonged to a race of human beings from another time for whom the awareness of higher order was placed above the materiality of life.”