From the Castle: Becoming Us

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/human-origins-Natural-History-Museum-631.jpg)

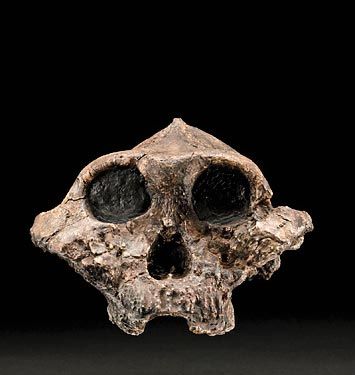

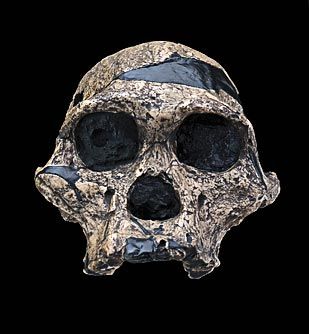

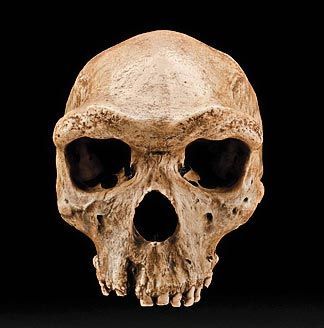

Why do our wisdom teeth often cause problems, and why do we have relatively hairless skin? The answers come from our distant past. Anyone with Internet access will soon be able to solve such mysteries in the Smithsonian’s compelling Web site, “Human Origins: What Does It Mean to Be Human?” (humanorigins.si.edu). The National Museum of Natural History’s new David H. Koch Hall of Human Origins, opening March 17, marks a milestone in the Institution’s long involvement with the study of early humans. Field research, 3-D and other digital images available to all on the Web site, educational and public programs will complement the new $20.7 million hall, which tells the epic story of how a single human species emerged over time and spread worldwide. Less well known is that during most of this journey, two or more species of early humans existed simultaneously. After several million years, one lineage led to...us! (See “Our Earliest Ancestors.”)

The 15,000-square-foot hall focuses on the ways defining characteristics of the human species developed as our ancestors adapted to a changing environment. A time tunnel introduces earlier human species. Visitors learn about major changes in climate and other key events in humanity’s evolution. And they look into the eyes of distant ancestors in forensically reconstructed life-size faces. More than 75 skull reproductions, a human family tree and virtual tours of key research sites illuminate our ancestors’ increasing brain size, technological expertise and artistic creativity. Lead curator Rick Potts says the hall will help define humanity’s “cultural and biological characteristics and how those traits emerged during one of earth’s most dramatic eras of environmental change.” Potts’ book, What Does It Mean to Be Human?, published in conjunction with the new hall, details the evidence for human evolution and for connecting the emergence of human traits to changes in climate over millions of years.

Our Human Origins initiative exemplifies the Smithsonian’s growing resources for teachers, students and lifelong learners. As Carolyn Gecan, a teacher in Fairfax County, Virginia, says: “I can now send my students on virtual field trips to Olorgesailie, Rick Potts’ field site in Kenya.” The initiative also demonstrates how our Web sites extend our reach hundreds-fold as we take our cutting-edge research, vast collections, exciting new exhibits and behind-the-scenes activities worldwide—inspiring wonder, encouraging curiosity and delivering knowledge, including explanations of why our wisdom teeth frequently cause trouble and why we aren’t covered in fur. (Our ancestors had larger jaws so they could chew tough food. With the development of tools and cooking, our food became easier to chew—and our jaws got smaller, often unable to accommodate wisdom teeth. Bare skin helps dissipate heat; in the places early humans evolved, overheating was more of a problem than being too cold.)

G. Wayne Clough is Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/wayne-clough-240.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/wayne-clough-240.png)