Food Historian Reckons With the Black Roots of Southern Food

In his new book, Michael Twitty shares the contributions that enslaved African-Americans and their descendants have made to southern cuisine

:focal(1846x1097:1847x1098)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c3/36/c33683a1-8dd5-4b0a-b29f-b5bd63c19312/dep2gp.jpg)

The kitchen is where Michael Twitty goes to tell the truth. It’s where he first came out as gay to his mother and aunt. Where he found a spiritual connection to Judaism in the braids of a challah, years before converting to the religion as an adult. Where he invites others to listen to his sermons about the true origins of southern food.

“It really is a place of dead honesty for me, both personally and professionally,” says the culinary historian. “I'm not gonna serve you bad food, dirty dishes, all of this nonsense. So, why am I gonna serve you facts that aren't supported? Why am I gonna serve you charming talk instead of truth?”

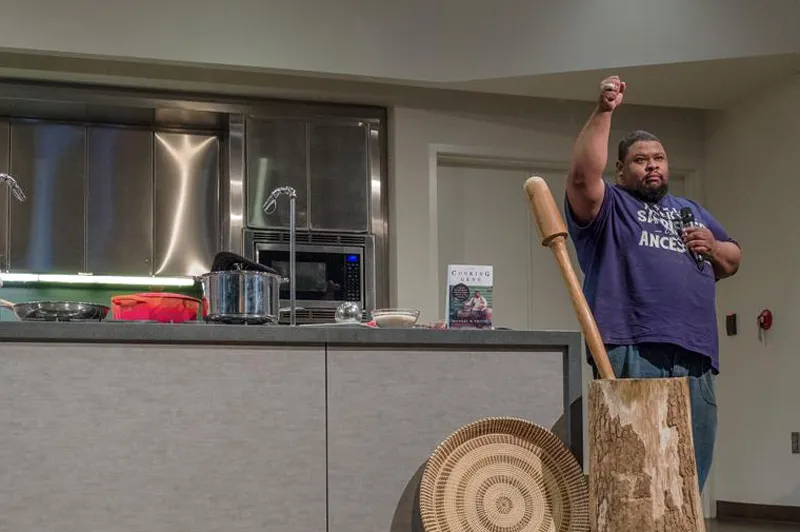

On a humid July day, Twitty is preparing a test kitchen demonstration on heirloom grains at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. Though he usually wears historically accurate period garb when cooking antebellum food, today he’s dressed in civilian clothes, wearing a dark blue t-shirt that reads “I will honor the sacrifices of my ancestors.”

“I think of it as a moral imperative to use food as a vehicle, as a lens to which to view things and to also transmit the truth and tell people really what's up,” says Twitty. He fingers the smooth granules of a rice strain named African Red Bearded Galberrina, while animatedly discussing its legacy in the soils of West Africa, the American South and southern Trinidad.

The story of the heirloom rice has largely been lost to history—the rice, which was grown in the Southern uplands after it was brought from West Africa more than 200 years ago, disappeared from the South by World War I in large part because black farmers who grew it found themselves pushed off of the lands they farmed. The rice’s legacy in the U.S. was erased, like so many other contributions that the millions of enslaved African Americans made to southern history, culture and, of course, cuisine.

“Michael is part of the avant garde that is going to change that,” says Glenn Roberts, the CEO of the Carolina Gold Rice Foundation, which is seeking to bring the durable African rice back to the American table.

Indeed, the food historian has become an essential voice in the conversation tracing the African roots of southern food. It’s become his life mission, he says, to unearth the complex stories of the region’s cuisine, drawing out the cultural intersections that shaped it.

“Our food is our flag,” Twitty would later tell the crowd that assembled at the American History Museum that day to hear him speak. “That’s why this is important. When I was growing up, I remember fifth-grade Michael Twitty was taught about his ancestors, like, oh, your ancestors were unskilled laborers who came from the jungles of West Africa. They didn’t know anything. They were brought here to be slaves and that’s your history.”

Twitty, a D.C.-area native, first struck up a passion for culinary history on a boyhood trip to Colonial Williamsburg in the 1980s. There he watched the old-timey food demonstrations, captivated. When he went home, he started experimenting with historical food. He hasn’t stopped.

After studying African-American studies and anthropology at Howard University, he embarked on his own journey to research African-American culinary heritage. He learned the art and craft of authentic antebellum cooking, gave lectures, travelled to conferences, and even gained first-hand experience working on historic plantations.

In 2011, though, he felt himself growing disconnected from the South. It had been some time since he’d visited the places where his ancestors lived and there were many sites in the South he had yet to see.

“I was actually pained by that because I felt inauthentic and I also felt like I was missing something, like there was something out there, something I wasn't seeing,” he says.

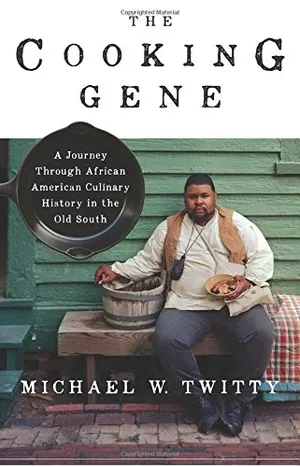

So he set out on a “Southern Discomfort Tour,” a journey to research his family history and sites of culinary memory in the South. He fed this experience into his new book, The Cooking Gene, a unique blend of personal, cultural and culinary history. He tells the story of the south through the cuisine that allowed his ancestors to sustain themselves, as he travels around the region himself to seek out his own family history, which he learns includes ancestors of West African, European and Native American descent.

The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South

A renowned culinary historian offers a fresh perspective on our most divisive cultural issue, race, in this illuminating memoir of Southern cuisine and food culture that traces his ancestry—both black and white—through food, from Africa to America and slavery to freedom.

In the book’s pages, woven alongside recipes for meals like West African Brisket (which requires paprika, black pepper, cinnamon, cayenne pepper and kosher salt, among other seasonings), he unearths tales of resilience, like how individuals once used mattress frames to barbecue deer, bear, hog, goat and sheep. “I was like no way in hell that a mattress frame was that big y'all could do all that. But more than one person told me till I found out it was actually a thing,” he says. “That was amazing. I was like, okay, people are doing things, they made that barbecue happen.”

He’s still looking for details of his own history, though. “Ever since Alex Haley's 'Roots,' everybody wants to have a genuine narrative of how their family transferred from Africa to America,” says Twitty. “It's not true for many us, we don't have it. To me that's the Holy Grail. To be able to figure out the ship, the trade routes. It's something I keep praying on. So I'm hoping that when people read this book, somebody might have another piece of the puzzle somewhere that I don't have, that can tell me what that's all about.”

During his tour, Twitty made national headlines when he penned an open letter to television personality Paula Deen after her use of racial epithets surfaced. Twitty was two years deep in his research at that point, and in the post, which he published on his food blog, “Afroculinaria,” he unpacks his frustrations with systematic racism as a whole and his disappointment with how the conversation around race and southern food continued to neglect the fact that enslaved Africans and their offspring had a significant hand in creating and innovating the food that Deen and so many others so happily championed.

He addresses Deen as a fellow southerner in the post, writing:

“This is an opportunity to grow and renew. If there is anything The Cooking Gene has taught me—it’s about the art of reconciliation. We aren’t happy with you right now. Then again some of the things you have said or have been accused of saying aren’t surprising. In so many ways, that’s the more unfortunate aspect. We are resigned to believe and understand that our neighbor is to be suspected before respected. It doesn’t have to be this way, and it doesn’t have to go on forever.”

In many ways, reconciliation is the thesis of The Cooking Gene. For Twitty, the word is not about forgiving and forgetting. Rather, it’s about confronting Southern history and addressing the complications ingrained in it. That’s why he begins The Cooking Gene with a parable of the elders in the Akan Culture of Ghana:

Funtunfunefu

There are two crocodiles who share the same stomach

and yet they fight over food.

Symbolizes unity in diversity and unity of purposes and

reconciling different approaches.

“For these cultures that are trying to figure out who and where and what enters and what leaves, it forms a crossroads,” says Twitty, an apt commentary on the state of the south today.

When it comes to the racism embedded in Southern food, that crossroad remains profoundly fraught. “Some of our most delicious food came to us through strife and oppression and struggle,” says Twitty. “Are we willing to own that and are we willing to make better moral choices based on that knowledge?”

It’s not a simple question. “Can you really handle the weight of your history? The baggage, the luggage? And if you can, what are you going to do with it?” he asks. “That's where I'm at right now.”

Twitty will be looking for answers, where else, but in the kitchen. As he walks on the stage at American History Museum, and takes his place behind at the makeshift counter, he begins the demonstration by explaining that story behind the red bearded rice, known for three centuries across continents, grown by enslaved people and by black farmers after the Civil War, a lost staple of the early American diet coming back to life in his careful hands.

Michael Twitty will be appearing at a Smithsonian Associates event which traces the history of Southern cooking on Thursday, August 10. Tickets can be purchased here.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.