Food From the Age of Shakespeare

By using cookbooks from the 17th century, one intrepid writer attempts to recreate dishes the Bard himself would have eaten

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/17-century-kitchen-631.jpg)

Enthralled by Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House stories when I was a young girl, I once made one of the frontier family’s staple dishes, a cornmeal porridge called hasty pudding. One of my fourth-grade classmates peered into the bubbling mixture and remarked, “Look, it’s breathing.” Undaunted, I’ve continued my forays into historical cookery, from the Mulligatawny stew popularized by British settlers in India to an American colonial dessert called slump. While my cooking is purely recreational, it sometimes takes inspiration from my professional life as a communications associate at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C. The library’s current exhibition, Beyond Home Remedy: Women, Medicine, and Science, which runs through May 14 and highlights medicinal remedies 17th-century women concocted to treat everything from gunshot wounds to rickets, got me thinking about cooking again. Women in England and colonial America were self-taught healers who compiled remedies along with their favorite recipes in notebooks then called “receipt” books. Handwritten instructions for making cough syrup might appear in the same volume—or even on the same page—as tips for stewing oysters.

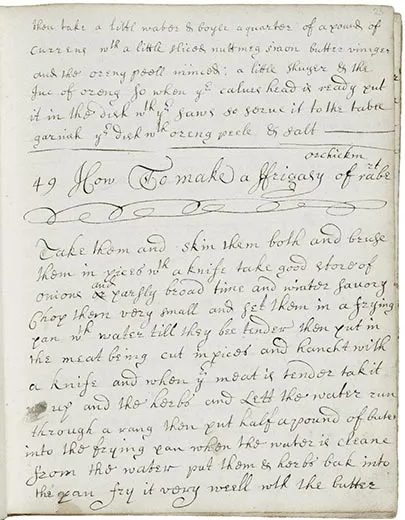

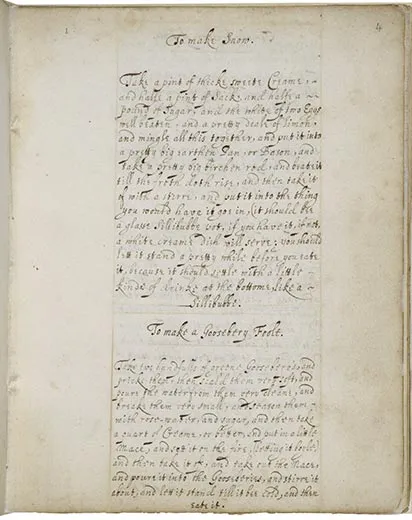

The Folger’s collection of several dozen receipt or recipe books offers a fascinating window into life during Shakespeare’s era on medical practices, women’s literacy and popular foods. Recipe books were often circulated among family members, and it’s not uncommon to see handwriting from several individuals in one book, says Rebecca Laroche, who curated the exhibition. As I scanned the neatly hand-scripted books by housewives Elizabeth Fowler and Sarah Longe, I got the urge to try some of their recipes. We know little about these women; they were literate, of course, and because Longe calls herself “mistress” and refers to King James I and Queen Elizabeth I in her book, historians surmise that she was informed and fairly well off, though not a member of the nobility. The notebooks, however, give us glimpses of the authors’ personalities.

Fowler had written her name and the date, 1684, on the cover and embellished them with swirls and curlicues. Her 300-page compendium includes poems and sermons. With an eye for organization, she numbered her recipes. Her recipe titles reflect her confidence in the kitchen: “To Make the Best Sassages that Ever was eat,” she labels one. Longe, whose 100-page bound vellum book dates from about 1610, also liberally sprinkles “good” and “excellent” in her recipe titles. But she attributes credit to others when appropriate: “Mr. Triplett’s Receipt for the Ague” or a cough syrup recipe “by D.R.”

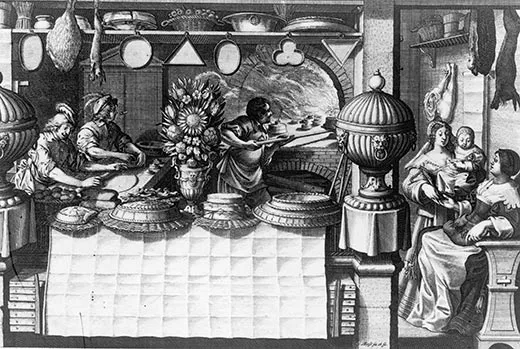

Mr. Triplett’s elixir calls for three gallons of aqua vitae, probably brandy or whiskey, and Longe’s recipe for a beef roast includes a pint and a half of wine. Alcohol was a common ingredient for medicine as well as cooking. Other culinary techniques included feeding herbs to caged birds to produce a flavorful meat and keeping fish alive in watertight barrels to ensure freshness.

To kitchen test historic recipes, I passed up Fowler’s recipe “How to Rost a Calves Head,” choosing instead her rabbit fricassee as a main course and Longe’s “Gooseberry Foole” as a dessert. A chilled mixture of fruit and cream, fools are still popular today in England. But fricassee is a rarity in contemporary cookbooks, though English colonists brought it to America and chicken fricassee was reputedly one of Abraham Lincoln’s favorite dishes. The name derives from a French dish that is basically cut-up meat cooked in a sauce. Gooseberries, a tart, grape-size fruit, are available fresh in the summer in this country but usually only in the Pacific Northwest, so I ordered them frozen from Washington State. They cost about $10 a pound, plus delivery fees. Although whole dressed rabbits are available locally in the Washington, D.C. area, I ordered pre-cut, deboned pieces (1.5 pounds for $30) from a gourmet meat retailer in New Jersey. Both berries and rabbit arrived at my doorstep via overnight delivery, packed in dry ice.

A major challenge to cooking from the days of yore is the dearth of details for cooking time, temperatures and ingredient quantities. Recipes may call for “a good store of onions” or instruct the cook to “lett it stand a great while.” Fowler did not specify how much winter savory for the fricassee, and Longe did not note how much sugar or rose water for the fool. One of the best professional cookbooks of the 17th century was Robert May’s The Accomplisht Cook, published in 1660. Drawing on his training in Paris and his career as a professional cook for English aristocrats, he often specifies quantities and cooking times, but that was not the case for many household recipe books. Technological limitations contributed to the vagueness of early recipes, says Francine Segan, food historian and author of Shakespeare’s Kitchen. The invention and availability of such devices as kitchen clocks and oven thermometers, as well as uniform measurements in the 1800s combined with a trend to make cooking more scientific, shifted the focus of recipes from personal taste and innovation to consistent, replicable results.

Segan’s personal view, however, is that’s today’s cooks are over-regimented. “A quarter of a teaspoon? Ludicrous!” she exclaims. “You have to be a cook and trust your palate.”

So I left my measuring spoons and cups in the cupboard and went on instinct.

The gooseberry fool was surprisingly easy. For color, I opted for ripe, red gooseberries instead of the pale green that Longe used. Per her instructions I scooped “two handfuls” in a bowl and used a spoon to “breake them very small.” With no guidelines for the amounts of sugar and rose water, I added what by my eye was about a half cup of sugar and several sprinkles of rose water. After the quart of cream had come to a “boyle,” I added a dash of nutmeg and folded in the gooseberry mixture. The fragrant rose water mingled with the aromatic spiced cream brought to mind a passage from Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream in which Titania, the fairy queen, is lulled to sleep in a forest of thyme and wild roses. “With sweet musk-roses and eglantine / There sleeps Titania.”

“Lett it stand till it bee cold,” Longe’s book instructed. I put the fool in the refrigerator, but during her day she might have chilled it in a root cellar or a purpose-built icehouse if she were lucky enough to afford one.

For the fricassee, I browned the pieces of rabbit in butter in a large skillet. I removed the meat, sautéed the chopped onions, parsley and thyme (a substitute for Fowler’s winter savory) and returned the rabbit to the pan and let it simmer about 20 minutes. I served the fricassee with peas and mashed potatoes. The common combination of herbs, onions and butter created a stew both savory and familiar, and the rabbit reminded me of chicken, but more flavorful and tender. My dinner guests ate with gusto, using the pan juices as gravy for the potatoes. Was this comfort food circa 1684?

As a finale, the fool was not quite as successful. Though delicately spiced, the mixture never fully solidified, leaving it a gloppy texture. Perhaps I didn’t boil the cream long enough. “A surprise to the palate,” said one guest puckering at the unfamiliar gooseberries. In my recipe makeover for the fool, I recommend raspberries, which have a delicate balance of sweet and tartness. Because we’re blessed with electrical appliances, I converted the fool recipe to a fast no-cook version. Over the centuries chicken became a popular fricassee meat and it will substitute well for the rabbit, which was common fare for our 17th-century ancestors. Fowler’s recipe called for a half pound of butter, but I used considerably less to spare our arteries.

As I offer these changes, I feel as if I’m scribbling a few notes in Sarah Longe’s and Elizabeth Fowler’s recipe books. Somehow, I don’t think they’d mind at all.