Fay Ray: The Supermodel Dog

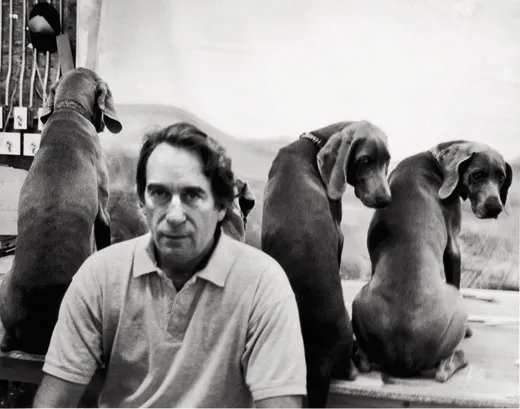

As photographer William Wegman tells it, his cinnamon-gray Weimaraner wasn’t content to just sit and stay

Fay Ray hadn’t had a lot of modeling experience when William Wegman put her on roller skates. He says that the image he titled Roller Rover was “one of the first” to feature his beloved cinnamon-gray Weimaraner. John Reuter, a Polaroid technician who assisted on the Roller Rover shoot in 1987 and on many other Wegman photo shoots, says it was “the first or second.” It is agreed, however, that the picture is a definitive example of the work that has made Wegman one of the world’s most widely known conceptual artists (as well as a powerful brand name), and that Fay Ray was destined to be a star from the moment she put on wheels.

She was 6 months old when Wegman first saw her, in 1985, a gift from a dog breeder in Memphis. The breeder had assumed Wegman was looking to replace Man Ray, the Weimaraner he’d turned into a ’70s icon in a number of droll photographs (Man Ray serenely being dusted with flour) and groundbreaking videos (Man Ray quizzically listening to Wegman read a school report card). Though the work lifted Wegman from the obscurity of a career teaching college photography into the upper echelons of the art world, it also left him a little grumpy—he once told an interviewer that he felt “nailed to the dog cross.” So when Man Ray died, in 1981, the artist thought he was done with dogs. Until he met the puppy from Memphis with what he recalls as “beautiful round, yellow eyes.”

Wegman took her home to New York City and named her after her predecessor and Fay Wray, the actress best known for her work in the original 1933 King Kong film. At first the dog seemed frightened of the city’s noise, and he thought he’d made a mistake in accepting her. He also thought he would never photograph her. “I felt sort of protective of Man Ray. I didn’t want to just come in and march on with the next version of that,” he told me recently.

Six months later, Fay was comfortable in her new home—so much so, Wegman says, that one day she “told” him, in the way that dogs tell things to the people who let them sleep in their beds, that she was ready to go to work. As Wegman recalls, the basic message was: “I didn’t come all the way from Tennessee to New York to lie around in your studio.” Soon dog and man were headed to Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he intended to photograph her with the same Polaroid 20x24 camera he’d used to make many of his Man Ray images.

As a young dog, Fay was happiest when confronting a challenge, Wegman says. “She liked things to be difficult. To just sit there and stay wasn’t interesting to her. She liked doing things that evoked a kind of awe in the spectators who watched her do them.” He thought the roller skates would fill the bill. Reuter has a slightly different memory: “We had a storage closet in the studio and she hid in there a lot.” Once she was placed in the skates, Wegman recalls, he took only two or three shots before they saw something they liked. Fay Ray brought an energy to the image that was entirely different from Man Ray’s, he says. “Man Ray filled the picture plane in a very solid way, and Fay sort of coiled into it.” And while Man Ray “was a larger and more static dog who projected a kind of stoic, Everyman thing...her eyes seemed to bring an electricity to the picture.”

Wegman insists he is not one of those people “who are so doggy, everything they do is sort of a dog thing.” You know that dogs are not like people, he says, “when they’re licking up the pizza that someone has run over with their car.” Wegman does anthropomorphize the animals in his work, but it’s done with purpose. Weimaraners are often described as having an aloof, “aristocratic” demeanor (like fashion models, Wegman has noted, they have a “cool, blank” gaze), making them perfect foils for the artist’s arid satire. In his photographs, he punctures that regal bearing by surrounding the animals with absurd artifacts from everyday human life. “A noble nature is diminished by platitude, a dignified mien degraded by unworthy aspiration,” art critic Mark Stevens wrote in a New York magazine review of Wegman’s 2006 exhibition “Funney/Strange.” The joke is on us and our shaky human ambitions, of course, and not the dogs. But we eat it up like dogs eat road pizza.

Wegman, 67, has become a cultural and commercial juggernaut whose work has been featured both in the Smithsonian American Art Museum and on Saturday Night Live. He also has a Weimaraner-motif fabric line, jigsaw puzzles featuring Weimaraner images, including Roller Rover, and more than 20 books of Weimaraner photographs. “I think artists who came out of the 1960s wanted to find other venues than galleries and museums,” he says. “For different reasons; it could have been Marxism, it could have been commerce, I don’t know.” Wegman’s work continues with a Weimaraner named Penny, who is the daughter of Bobbin, who is the son of Chip, who was the son of Batty, who was the son of Fay Ray, who died in 1995 after a full life serving the demands of art and commerce.

David Schonauer, former editor in chief of American Photo, has written for several magazines.