Europe’s Small House Museums

Sir John Soane’s Museum in London and other idiosyncratic house museums in Europe yield pleasures beyond their size

What is it about small, quirky museums that makes them so compelling? Perhaps it's because they can be traced to antiquity, when Greco-Roman temples would display both wondrous artworks and pagan relics—the spear of Achilles, Helen of Troy's sandal, or "giants' bones" (usually petrified mammoth remains). Medieval cathedrals carried on the tradition: tortoise shells or "griffin's eggs" (actually those of ostriches) might be placed alongside the relics of saints. In the Renaissance, Italian princes began assembling cabinets of curiosities, eclectic displays that could include any creation of man or nature: Egyptian mummies, pearls, Classical sculptures, insects, giant seashells or "unicorn horns" (most often from narwhals). The Italian collecting mania spread, so that by the end of the 18th century, there were thousands of private galleries in affluent homes all over Europe. On their grand tours of the Continent, travelers could journey from one marvelous living room to the next, surveying beautiful and mystifying objects.

By the mid-1800s, state-funded institutions such as the Louvre, the British Museum and Madrid's Prado had begun to acquire these private collections, many of which had been inherited by family members who lacked either the finances or the enthusiasm to maintain them. Yet despite large museums' financial advantage, small, esoteric museums have held on tenaciously. In fact, Europe is still full of them, and they induce a devotion that their grander counterparts often do not.

Many of these small collections are still housed in their owners' original homes and reflect their personalities. A number of them boast collections that would have pride of place in larger museums, but the domestic settings allow a sense of intimacy hard to find in vast galleries. And despite their idiosyncrasies, these house museums often provide a rare entree into a city's history and character. Here are four favorites:

London

Sir John Soane's Museum

It was a damp London evening when I crossed the large, leafy square of Lincoln's Inn Fields toward a tasteful row of dun-colored Georgian town houses. On closer inspection, the facade of No. 13 announced this was no ordinary house: mortared into the Italian loggia, or veranda, of creamy Portland stone were four Gothic pedestals, while a pair of replicas of ancient Greek caryatids were mounted above. But these flourishes only hinted at the marvelous world that lies within the former home of Sir John Soane (1753-1837), one of Britain's most distinguished architects—and diligent collectors. Soane not only turned his house into a lavish private museum, he provided that nothing could be altered after his death. As a result, Sir John Soane's Museum may be the most eccentric destination in a city that brims with eccentric attractions. Visiting it, you feel that Soane himself might stride in at any moment to discuss the classics over a brandy. To preserve the intimacy of the experience, only 50 visitors are allowed inside at a time. And the evocation of a past time is even more intense if you visit—as I did—on the first Tuesday evening of the month, when the museum is lit almost entirely by candles.

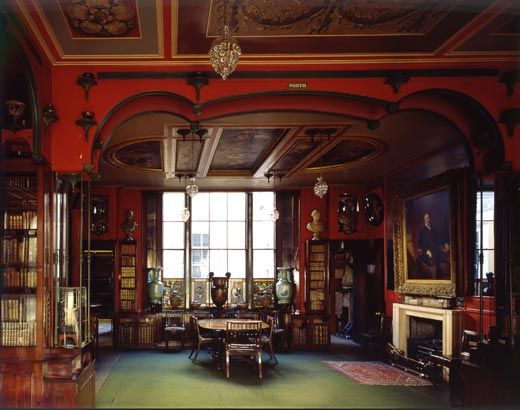

When I rang the bell, the imposing wooden door opened to reveal a gray-haired gentleman who might well have been Soane's butler. While I signed the guest ledger, an attendant fussed over my coat and umbrella, taking them for safe- keeping. I was then ushered into a Pompeian red parlor.

"I hope you enjoy the house," the attendant whispered.

On every table and mantel, candles blazed in glass cylinders. As I padded carefully down a passageway, my eyes adjusted to the light and I began to make out arrangements of artifacts and furniture that have barely changed in 170 years. The house is an intricately designed labyrinth, filled to capacity with art: Classical busts, fragments of columns and Greek friezes, Chinese vases, and statues of Greek and Roman gods, including a cast of the famed Apollo Belvedere. Scarcely an inch of wall space has been wasted, and yet the effect is not claustrophobic: arches and domes soar upward, convex mirrors provide expansive views and balconies yawn over interior courtyards. Like any decent cabinet of curiosities, the displays also include such oddities as a "large fungus from the rocks of the island of Sumatra" (as Soane described it in his own 1835 inventory) and a peculiar-looking branch of an ash tree. Adding to the sense of mystery, and in keeping with Soane's wishes, there are no labels on any of the artifacts, though some information is now provided on hand-held wooden "bats" that sit discreetly on tables in each room.

"People really respond to the candlelit evenings," says the museum's director, Tim Knox. In fact, warders, as the museum's guards are called, have begun turning off lights during the daylight hours, he tells me, "to enhance the period ambiance. The half-light makes people really look at the exhibits."

Soane was Britain's leading architect for nearly five decades, and his numerous commissions are all around London—the Dulwich Picture Gallery; the Royal Hospital, Chelsea; Pitzhanger Manor-House. (Even Britain's iconic red telephone booths were inspired by Soane's design for his wife's tomb in St. Pancras Gardens.) But it was in his own home—designed to emphasize what Soane called the "fanciful effects which constitute the poetry of Architecture"—that his creativity was given freest rein. From 1792 to 1824, Soane purchased, demolished and rebuilt three town houses along the square, starting with No. 12 and moving on to 13 and 14. Initially they were home to himself, his wife and their two sons, but starting in 1806, when he was appointed professor of architecture at the Royal Academy, he began to use them to display his architectural designs and models. In time, his growing collection of antiquities became more important, and with endless inventiveness, he redesigned his interiors to show off the artifacts to full effect.

Objects were placed so that every turn offers a discovery. One minute you are confronting a splendid Roman marble statue of Diana of Ephesus. The next, you are entering the Picture Room, lined with paintings such as Hogarth's Rake's Progress, a series of eight images charting the decline of a hedonistic young aristocrat. No sooner have you finished admiring an array of Piranesi drawings of Roman ruins than a warder opens a panel in the wall to reveal a group of paintings by Joseph Michael Gandy, Soane's draftsman. The gray-templed warder, Peter Collins, sports a carnation in his lapel and a red handkerchief in his top pocket. He has worked at the museum for ten years and knows his audience. He pauses for effect before opening yet another panel, this time revealing a balcony that looks out on the Medieval collection—called the Monk's Par-lour—filled with Gothic fragments and grimacing gargoyles. In a nearby alcove, a bare-breasted bronze nymph poses coyly at eye level above a scale model of Soane's most impressive architectural achievement, the Bank of England. (The bank, which he worked on for 45 years, was demolished in the 1920s as outmoded—a move that many architectural historians regard as a travesty.)

The highlight of the collection is found in the basement, where funerary art clutters around the alabaster sarcophagus of Egyptian Pharaoh Seti I—Soane's pride and joy, purchased in 1824 for the sum of £2,000 (about $263,000 today) from the Italian adventurer Giovanni Belzoni. In 1825 Soane held a series of candlelit "sarcophagus parties" to celebrate its arrival. The social extravaganzas were attended by such luminaries as the Duke of Sussex, the Bishop of London, poet Samuel Cole- ridge and landscape painter J.M.W. Turner. Barbara Hofland, a guest, would write that at the event figures emerged like ghosts from the "deep masses of shadows" and candles shone "like lustrous halos round marble heads," creating an effect "as in a dream of the poet's elysium."

Among the many statues in the museum, it's easy to miss the 1829 bust of Soane himself on the first floor, placed above statuettes of Michelangelo and Raphael. The son of a bricklayer, Soane rose from humble origins; for his skill at sketching, he won a scholarship to tour Europe, which enabled him to visit Italy and develop a passion for Greco-Roman art. When he died at the ripe age of 83, Soane was one of the most distinguished individuals in Britain, a man, as Hofland wrote of the sarcophagus party guests, seemingly "exempt from the common evils of life, but awake to all its generous sensibilities."

This happy impression is reinforced by a Gandy drawing of the family in 1798: Soane and his wife, Elizabeth, are eating buttered rolls while their two young sons, John and George, scamper nearby. Of course, Soane was no more immune to fate's vagaries than the rest of us. His fondest ambition had been to found a "dynasty of architects" through his sons, but John was struck down in his 30s by consumption and George grew up to be quite the rake, running up huge debts and even publishing anonymous attacks on his father's architecture. Then too, Soane may not have been the easiest father. "He could be a man of great charm," says museum archivist Susan Palmer, "but he was also very driven, very touchy and moody, with a real chip on his shoulder about his poor origins."

Fearing that George would sell his collection when he died, Soane provided for its perpetuation in his will and was able to secure an act of Parliament in 1833 to ensure that his home would remain a venue, as he wrote, for "Amateurs and Students in Painting, Sculpture and Architecture." As a result, Soane's museum is run to this day by the Soane Foundation, although in the 1940s the British government took over the costs of maintenance in order to keep it free to the public, as it has been since Soane's death in 1837. "Thank goodness Mr. Soane didn't get on with young George," one of the warders observed with a laugh. "I'd be out of a job!"

I shuffled downstairs through the half-light, reclaimed my coat and umbrella and headed for the Ship Tavern, a 16th-century pub around the corner. As I dug into a shepherd's pie, I recalled the words of Benjamin Robert Haydon, another sarcophagus party guest: "It was the finest fun imaginable to see the people come into the Library after wandering about below, amidst tombs and capitals, and shafts, and noseless heads, with a sort of expression of delighted relief at finding themselves again among the living, and with coffee and cake."

Paris

Musée Jacquemart-André

There are dozens of small museums scattered throughout Paris, and their most devoted patrons are Parisians themselves. Some have substantial collections, like the Musée Carnavalet, which specializes in the city's dramatic history and displays such items as a bust of Marat, a model of the Bastille and locks of Marie Antoinette's hair. Others are the former residences of hallowed French artists and writers—the studio of Delacroix, the apartment of Victor Hugo and the appealingly down-at-the-heels Maison Balzac, whose most illustrious exhibit is the author's monogrammed coffeepot.

But none inspire such loyalty as the Jacquemart-André.

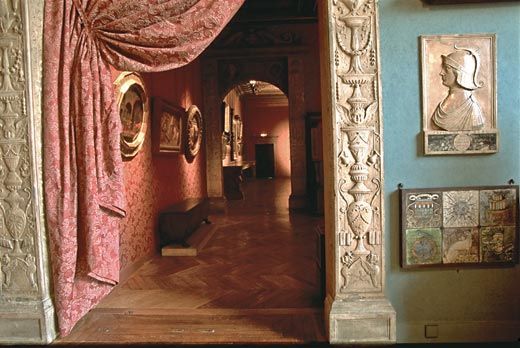

If Sir John Soane's Museum distills the eccentric genius of London, the Musée Jacquemart-André is the height of le bon goût, good taste. More a mansion museum than a house museum, it was nonetheless home to connoisseurs Édouard André and his wife, Nélie Jacquemart, a fabulously wealthy couple who in the 1880s and '90s built their own self-contained world of art and beauty on the Boulevard Haussmann—a fashionable avenue on the Right Bank, not far from the Champs-Élysées—replete with masterpieces that Louvre curators undoubtedly covet to this day.

At first glance, the museum could not be more different from Soane's. Bursting with color, it exudes a luxuriant sense of space. But no less than Soane's, it sweeps visitors back to another era—in this case, the Paris of La Belle Époque, when the city blossomed as Europe's capital of elegance, and to the even earlier golden age of Louis XV and Louis XVI.

No sooner does one step from the old carriage driveway into a formal courtyard than the sound of Parisian traffic fades away. Ascending wide stone steps graced by sculpted lions, one feels a flush of privilege, like a guest who has been invited to a private soirée. Inside, one is met by a three-quarter-length portrait of the master himself, Édouard André—a dashing figure in the uniform of the Imperial Guard under Emperor Napoleon III, complete with gold brocade and scarlet breeches. A manicured gardienne ushers guests into the Picture Gallery, where the seduction continues. André had a passion for 18th-century French art, fueled by his nostalgia for pre-Revolutionary days, and the first floor is devoted to it. On gilt-framed canvases, voluptuous goddesses float naked on clouds and rosy-cheeked children pose with birds and kittens. A visitor drifts from the gilded Grand Salon to the soaring Music Room, where formally attired guests once gathered for concerts, then on to the glass-roofed Winter Garden, filled with exotic plants and gleaming marble, where an extravagant double staircase spirals up to the second floor.

And so the house unfolds, offering one dazzling gallery after another. The Library, where Édouard and Nélie pored over art catalogs and plotted their purchases, is home to their world-class array of Dutch paintings, including three Rembrandts and three Van Dycks. Japanese ceramics and Persian antiquities enliven the Smoking Room, where Édouard would retire after dinner with his male companions to smoke cigars and discuss the issues of the day, while the Tapestry Room, used for business meetings, is lined with scenes of Russian peasant life created by the Beauvais Tapestry factory in 1767. As one climbs to the second floor, a playful Tiepolo fresco on the staircase wall depicts the arrival of Henry III in Venice. The upper level is devoted to the couple's "Italian Museum"—one room for Renaissance sculpture, a second for Florentine art, including two paintings by Botticelli, and a third room for André's beloved collection of the art of Venice.

The mansion, which was designed for André by architect Henri Parent, was completed in 1875, when the Boulevard Haussmann was one of Paris' chic new addresses and André was one of the city's most eligible bachelors. Heir to an enormous banking fortune, he had grown disillusioned with public life and decided to devote himself to collecting art and publishing a fine arts journal. In 1881, when he was nearly 50, he married Nélie Jacquemart, the woman who had painted his portrait nine years earlier. In many ways, she was an unlikely match for this aristocratic boulevardier. Nearly 40 herself, Jacquemart was no high-society belle. She was an independent woman from a humble background—evidently illegitimate—who had supported herself as a portrait artist, quite an unusual achievement for a woman at the time.

It was a marriage based on shared taste. During their 13 years together, the couple traveled for part of each year, most often to Italy, where they attended auctions with the help of experts from the Louvre, who were motivated to win art for France. After Édouard died in 1894, at age 61, Nélie continued traveling the world, going as far as Burma for her purchases. On her death at 71 in 1912, she donated the house to the Institut de France (an academic organization that manages foundations and museums) on the condition that the collection remain intact, so that the French public could see, she said in her will, "where a pair of amateur art-lovers lived out a life of enjoyment and luxury."

Indeed, there is enormous pleasure to be taken from seeing the couple's paintings and sculptures mixed in with their objets d'art and fine furniture in a domestic setting. After a while, however, even the finest taste can be a little overbearing. Visitors can't help but speak in hushed tones so as not to upset the exquisite equilibrium.

But the mansion bursts to exuberant life in the Dining Room—the former heart of the original mansion—which has been converted into one of Paris' most sumptuous café-restaurants. In this airy chamber, where the couple entertained friends beneath lavish tapestries, one can now enjoy a salade niçoise and glass of sauvignon blanc. There is a strange feeling of being watched here, and not just by fellow diners: the ceiling is a marvelous joke, another Tiepolo fresco—this one depicting a crowd of Venetian nobles leaning over a balustrade, pointing and smiling at the diners below.

Perched on the mantelpiece is a bust of Nélie Jacquemart. She many not have fit in with the city's fashionable set—later in life, she retired to her rural chateau, Chaalis, today another grand house museum, 30 miles outside the city—but she certainly took a fierce pride in her collection, and one imagines her still basking in the pleasure it creates.

Madrid

Museo Sorolla

Madrid is a city of extravagant facades whose true attractions lie behind closed doors. Hidden beyond a stone wall in the former working-class district of Chamberí, a ten-minute taxi ride from the bustle of the Plaza Mayor in downtown Madrid, lies the sun-filled Museo Sorolla. The former home and art studio of one of Spain's most beloved painters, Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida, it is a succulent garden of tinkling fountains and exuberant flowers, an explosion of Mediterranean color and joie de vivre.

From 1911 to 1923, this Andalusian-style house was the residence of one of the world's best-known artists. Born to a humble family in Valencia in 1863, Sorolla kept his distance from Europe's avant-garde movements but won international fame for his subtle technique, evoking the play of sunshine in his scenes of Mediterranean beaches and images of Spanish daily life.

Stepping into the seductive confines of the compound, where Sorolla lived with his wife and three children, is like entering one of the artist's luminous paintings. With its Moorish flourishes, tranquil pools and ever-present sound of flowing water, the garden was the place where he most loved to paint. When I visited, Sorolla's private Arcadia was filled with earnest art students experimenting with watercolors in shady corners. Tiled steps lead up to the house, whose first rooms display his works, just as they did 80 years ago for potential buyers. The home's living spaces contain the family's original Art Nouveau furniture and Tiffany lamps. But the emotional core of the house is Sorolla's studio, a large vaulted room painted a rosy red and suffused with sunshine. Sorolla's easels stand ready, as if he had just left for a siesta; his palettes, brushes and half-used paint tubes are close by. A small Turkish bed occupies one corner of the room and a book of 16th-century songs sits open on a stand. A drawing Sorolla made of Velázquez's famous portrait of Pope Innocent X presides over all.

Sorolla moved into the house, which he had built, in 1911, at the high point of his career. By then he had exhibited his work from London to St. Louis, Missouri, had been showered with international awards, befriended intellectuals and artists, including John Singer Sargent, painted the portrait of Spanish King Alfonso XIII and U.S. President William Howard Taft and, under the patronage of railroad-fortune heir Archer Huntington, had been commissioned to paint a vast mural in the Hispanic Society of America in New York City.

After his death at 60 in 1923, Sorolla's international reputation suffered, overshadowed by the work of Post-Impressionists such as Cézanne and Gauguin. As with his friend Sargent, many critics decided that Sorolla was too conservative and commercial. But in Madrid, Sorolla's artistic standing has never been shaken, and since its opening by his widow and son in 1931, the Museo Sorolla, which also houses the most extensive collection of his works in the world, has enjoyed a steady stream of pilgrims. Today, their faith is being vindicated; Sorolla is being reevaluated by critics, who are placing him as a bridge between Spanish old masters such as Velázquez and Goya and the Post-Impressionists. In 2006, Madrid's prestigious Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum hosted "Sargent/Sorolla," an exhibition tracking the parallel careers of the pair.

At the Museo Sorolla, as in all house museums, a chord of melancholy intrudes: the artist, we learn, was painting a portrait in his beloved garden in 1920 when, at the age of 57, he suffered a stroke. Although he lived for another three years, he produced little new work. But such gloomy meditations do not suit the house, or the sensual spirit of modern Madrid. The best solution—as Sorolla himself would likely have agreed—is to head to a nearby café to sip a glass of vino blanco and bask in the Spanish sun.

Prague

The Black Madonna House: The Museum of Czech Cubism

Unscathed by two world wars, the heart of Prague feels like a fantasy of Old Europe. Gothic spires frame Art Nouveau cafés, and on the Medieval Astronomical Clock, next door to Franz Kafka's childhood home in the Old Town Square, a statue of Death still pulls the bell cord to strike the hour. But if you turn down a Baroque street called Celetna, you confront a very different aspect of the city—the stark and surprising Black Madonna House, one of the world's first Cubist buildings and home today to the Museum of Czech Cubism. Designed by Prague architect Josef Gocar, the House was shockingly modern, even revolutionary, when it opened as a department store in 1912—and it still seems so today. The overall shape is appropriately boxlike and predictably austere, but on closer inspection the facade is broken up by the inventive use of angles and planes. Large bay windows protrude like quartz crystals, and angular ornamentation casts subtle shadows. The interior is no less unusual, with the city's first use of reinforced concrete allowing for the construction of generous open spaces. The House's peculiar name comes from the 17th-century statue of the Black Madonna and Child rescued from a previous structure on the site and now perched like a figurehead on one corner of the building.

But not even the Madonna could protect the House from the vagaries of Czech history. Following World War II and the Communists' rise to power, the department store was gradually gutted and divided into office space. After the 1989 Velvet Revolution ended Communist rule, the building had a brief life as a cultural center, but it was only in 2003 that it found its logical role in the fabric of Prague—as a shrine to the glories of Czech Cubism.

Most of us think of Cubism as an esoteric avant-garde movement advanced by Parisian artists Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque and others in the years before World War I. But the movement swept across Europe and was embraced in Russian and Eastern European capitals as well—nowhere more avidly than in Prague, where Cubism was seized upon, if only for an incandescent moment, as a possible key to the future.

"In Paris, Cubism only affected painting and sculpture," says Tomas Vlcek, director of the Collection of Modern and Contemporary Art at the country's National Gallery, which oversees the Museum of Czech Cubism. "Only in Prague was Cubism adapted to all the other branches of the visual arts—furniture, ceramics, architecture, graphic design, photography. So Cubism in Prague was a grand experiment, a search for an all-encompassing modern style that could be distinctively Czech."

The coterie of Czech Cubists—principally Gocar, Otto Gutfreund and Bohumil Kubista—first came together in 1911, founding a magazine called Artistic Monthly and organizing their own exhibitions in the years before World War I. It was a time of intense optimism and energy in Prague. This small Eastern European metropolis, one of the wealthiest in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, drew on its vibrant Czech, German and Jewish traditions for a creative explosion. Expatriate artists were returning from Paris and Vienna to share radical new ideas in the salons; Kafka was scribbling his first nightmarish stories; Albert Einstein was lecturing in the city as a professor. "It was something like paradise," says Vlcek, looking wistful.

Today, the Museum of Czech Cubism is a shrine to the movement's heyday (1910-19), with the building itself as the prime exhibit. The entryway is an angular study in wrought iron. Inside, one immediately ascends a staircase of Cubist design. Unlike the stairs in Marcel Duchamp's Nude Descending a Staircase, the steps are thankfully even, but the metal balustrade is a complex interplay of geometric forms. There are three floors of Cubist exhibits, filled with art forms unique to Prague. Elegant sofas, dressing tables and lounge chairs all share dramatically oblique lines. There are abstract sculptures and paintings, bold, zigzagging graphics, and cockeyed vases, mirrors and fruit cups.

While this may not be strictly a house museum, it does have a domestic feel. The many black-and-white portraits of obscure artists in bowler hats and bow ties reveal a thriving, bohemian cast of characters: one sofa, we learn, was "designed for the actor Otto Boleska," another for "Professor Fr. Zaviska." What sounds like a Woody Allen parody of cultural self-absorption captures the idiosyncratic nature of Prague itself, a city that takes pride in its most arcane history. And like all small museums in touch with their origins, unique features have brought ghosts very much back to life. Visitors can now retire to the building's original Cubist eatery, the Grand Café Orient, designed by Gocar in 1912. This once-popular artists' hangout was closed in the 1920s and gutted during the Communist era, but meticulous researchers used the few surviving plans and photographs to recreate it. Now, after an eight-decade hiatus, a new generation of bohemians can settle in beneath Cubist chandeliers in Cubist chairs (not as uncomfortable as they sound) to argue politics over a pint of unpasteurized Pilsener. Finally, on the ground floor, the museum store has recreated a range of Cubist coffee cups, vases and tea sets from the original designs of architect and artist Pavel Janak, and offers reproductions of Cubist furniture by Gocar and others.

After an afternoon immersed in all those angles, I began to notice subtle Cubist traces in the architectural cornucopia of Prague's streets—in the doorway of a former labor union headquarters, for example, and on an elegant arch framing a Baroque sculpture next to a church. Inspired, I decided to track down a Cubist lamppost I had heard about, designed in 1913 by one Emil Kralicek. It took a little wrestling with Czech street names, but I finally found it in a back alley in the New Town: it looked like a stack of crystals placed on end.

I could imagine Sir John Soane—transported to modern Prague—pausing before it in unabashed admiration.

Tony Perrottet's latest book, Napoleon's Privates, a collection of eccentric stories from history, is out this month from HarperCollins.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)