Emmett Till’s Casket Goes to the Smithsonian

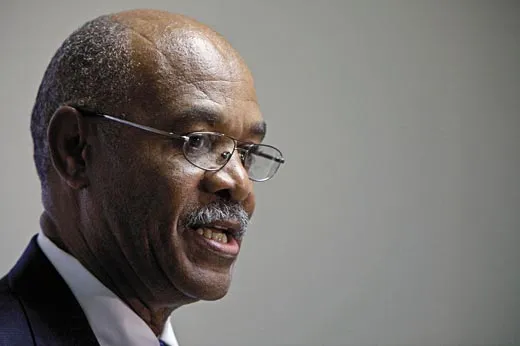

Simeon Wright recalls the events surrounding his cousin’s murder and the importance of having the casket on public display

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/QA-Simeon-Wright-631.jpg)

In 1955, Emmett Till—a 14-year-old African-American visiting Mississippi from Chicago—was murdered after whistling at a white woman. His mother insisted that her son be displayed in a glass-topped casket, so the world could see his beaten body. Till's murder became a rallying point for the civil rights movement, and his family recently donated the casket in which he was buried to the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. Till's cousin Simeon Wright, 67, who was with him the night he was kidnapped and murdered, spoke with the magazine's Abby Callard.

What was Emmett like?

He loved to tell jokes and loved for people to tell him jokes. In school, he might pull the fire alarm just to get out of class. To him that would be funny. We found out that what was dangerous to us was funny to him. He really had no sense of danger.

What happened at the store between Emmett and Carolyn Bryant has been debated, what do you remember happening?

We went to the store that night. My nephew that came down from Chicago with Emmett went into the store first, and Emmett went in the store after him. So Wheeler came out, and Maurice sent me inside the store to be with him to make sure he didn't say anything out of line. There was about less than a minute that he was in there by himself. During that time I don't know what he said, but when I was in there, he said nothing to her. He didn't have time, she was behind the counter, so he didn't put his arms around her or anything like that. While I was in there he said nothing. But, after we left the store, we both walked out together, she came outside going to her car. As she was going to her car, he did whistle at her. That's what scared her so bad. The only thing that I saw him do was that he did whistle.

Because he was from Chicago, do you think Emmett's unfamiliarity with the South during the Jim Crow era contributed to what happened?

It could have been the reason he did it, because he was warned not to do anything like that, how he was supposed to act. I think what he did was trying to impress us. He said, "You guys might be afraid to do something like this, but not me." Another thing. He really didn't know the danger. He had no idea how dangerous that was; because when he saw our reaction, he got scared too.

You were in the same bed as Emmett when the two men came for him, right?

Yes, when they came that night, that Sunday morning, he and I were in the same bed. I was the first one to wake up because I heard the noise and the loud talking. The men made me lie back down and ordered Emmett to get up and put his clothes on. During that time, I had no idea what was going on. Pretty soon, my mother came in there pleading with them not to take Emmett. At that point, she offered them money. One of the men, Roy Bryant, he kind of hesitated at the idea but J.W. Milam, he was a mean guy. He was the guy with the gun and the flashlight, he wouldn't hear of it. He continued to have Emmett put his clothes on. Then, after Emmett was dressed, they marched him out of the house into a truck that was waiting outside. When they got out to the truck, they asked the person inside the truck, "Was this the right boy." A lady's voice responded that it was.

You attended the trial. Were you at all surprised that the murderers were acquitted?

I was shocked. I was expecting a verdict of guilty. I'm still shocked. I believe sincerely that if they had convicted those men 54 years ago that Emmett's story wouldn't have been in the headlines. We'd have forgotten about it by now.

Your family left Mississippi after the trial, right?

My mother left the same night [he was taken]. She left that house, she didn't leave Mississippi, she left that house and went to a place called Sumner, where they had the trial. Her brother lived in Sumner, and she stayed there until his body was found. She was on the same train that his body was going back to Chicago. We left, my dad and my two brothers, left the Saturday, the Monday after the verdict. The verdict came in on a Friday, I believe, that Monday we were on a train headed to Chicago.

Why did you leave?

My mother was, she was so scared and there was no way that my dad was going to be able to live there anymore. After the verdict, my dad was so disappointed. He had had enough of Mississippi. He had heard of things like this happening to African Americans, but nothing had ever happened to him like that—firsthand victim of racism, and the Jim Crow system. He said that was enough. He just didn't want no part of Mississippi anymore.

How did you and the rest of your family feel about Emmett's mother's decision to hold the funeral with an open casket?

Well, an open casket is a common thing in African American tradition. But one of the reasons they didn't want her to open the casket was because of the stench, because of the smell. They designed the casket with the glass over it and what not. She said it herself, she wanted to world to see what those men had done to her son because no one would have believed it if they didn't the picture or didn't see the casket. No one would have believed it. And when they saw what happened, this motivated a lot of people that were standing, what we call "on the fence," against racism. It encouraged them to get in the fight and do something about it. That's why many say that that was the beginning of the civil rights era. From experience, you can add, what they mean by that is we was always as a people, African Americans, was fighting for our civil rights, but now we had the whole nation behind us. We had whites, we had Jews, Italians, Irishmen jumping in the fight, saying that racism was wrong.

How did the casket become available?

In 2005, we had to exhume Emmett's body. The State of Mississippi would not reopen the case unless we could prove that the body buried at the cemetery was Emmett's. State law prohibited us from placing that casket back into the grave, so we had to bury him in a new casket. We set this casket aside to preserve it because the cemetery was planning on making a memorial for Emmett and his mother. They was going to move his mother and have the casket on display. But you see what happened, someone took the money and discarded the casket in the shed.

How did you find out about the casket?

A radio personality called me about six in the morning asking me questions about it. They were on top of what was going on at the cemetery. I told him what was supposed to happen to the casket. He kept asking me questions and I said "Wait a minute, let me go out there and check and see. I don't know what's going on. Let me go out to cemetery and get some answers, find out what's going on out there." That's when I saw the casket sitting in the shed deteriorating. The last time my cousin saw the casket it was inside of the building, preserved. We don't know who moved it out into the shed but I got a chance to see it, it was just horrible the way they had discarded it like that without even notifying us. They could have called the family, but they didn't.

Why did you decide to donate the casket to the Smithsonian?

Donating it to the Smithsonian was beyond our wildest dreams. We had no idea that it would go that high. We wanted to preserve it, we wanted to donate it to a civil rights museum. Smithsonian, I mean that's the top of the line. It didn't even cross our mind that it would go there, but when they expressed interested an in it, we was overjoyed. I mean, people are going to come from all over the world. And they're going to view this casket, and they're going to ask questions. "What's the purpose of it?" And then their mothers or fathers or a curator, whoever is leading them through the museum, they'll begin to explain to them the story, what happened to Emmett. What he did in Mississippi and how it cost him his life. And how a racist jury knew that these men were guilty, but then they go free. They'll get a chance to hear the story, then they'll be able to... perhaps, a lot of these young kids perhaps, they will dedicate their lives to law enforcement or something like that. They will go out and do their best to help the little guys that can't help themselves. Because in Mississippi, in 1955, we had no one to help us, not even the law enforcement. No one to help us. I hope that this will inspire our younger generation to be helpers to one another.

What feelings do you experience when you see the casket today?

I see something that held the object of a mother's unconditional love. And then I see a love that was interrupted and shattered by racial hatred without a cause. It brings back memories that some would like to forget, but to forget is to deny life itself. For as you grow older, you are going to find out life is laced with memories. You're going to talk about the good old days. When you get 50, you're going to talk about your teenage days. You're going to listen to music from the teenage days. You don't have to believe me, just trust me on that. I'm not talking about what I read in a book. I'm talking about what I've experienced already. Also, it brings to our memories where we have been and where we are now and where we're going. People look at this casket and say, "You mean to tell me this happened in America?" And we will have a part of the artifacts from that era to prove to them that things like this went on in America. Just like the Civil War. By histories of the Civil War. Even today, it seems impossible to me that the Civil War took place in America. Here you have white fathers and sons fighting against each other. Mothers and daughters fighting against each other because one felt that slavery was wrong and one felt that it was all right. And they began to kill each over that. That's hard for me to believe but I see the statues. I see the statues of the solders, the Union soldiers and the Confederate soldiers, and it just helps us to believe the past. This casket's going to help millions to understand and believe that racism, the Jim Crow system, was alive and well in America back in 1955.

What is your hope for the casket?

Well, I hope, I know one thing, it's going to speak louder than pictures, books or films because this casket is the very image of what has been written or displayed on these pictures. I hope it's going to make people think "If I had been there in 1955, I would have done all I could to help that family." If it could just evoke just that one thought in someone, it would be enough, because then they would go out and help their fellow man, their community and the church and the school, wherever. We have, you know, I just had a couple of months ago a young man, 14 years of age, committed suicide because of bullies in his school. If it could just evoke that one emotion, that "if I had been there, I would have helped you." That's all I want.

In what ways do you feel that Emmett's story is still relevant today?

You know, it's amazing that he is still relevant. Like I said at the beginning, the reason is because of the jury's verdict. If the jury's verdict had come in guilty, Emmett would have been forgotten about. But [Emmett's story] shows people that if we allow lawlessness to go on, if we do nothing to punish those who break the law, then it's going to get worse. It's going to get worse. And we can look back and say, look what happened to Emmett. He was murdered for no reason, and those in charge did nothing about it. Wherever you have that, whatever city you have that in, it could be in Washington, it could be in New York, where you have murder and crime going on and the people do nothing about it, it's going to increase and destroy your society.

Wright's book, Simeon's Story: An Eyewitness Account of the Kidnapping of Emmett Till (Lawrence Hill Books) will be released in January 2010.