The Failed Attempt to Design a Memorial for Franklin Roosevelt

The debacle of the Eisenhower memorial is only the most recent entry in a grand D.C. tradition of fraught monuments

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/37/b5/37b5aca4-7586-4e21-b80f-301776a3cd62/fdr-memorial-breuer-1.jpg)

Frank Gehry, who you might remember from such TV shows as “The Simpsons” but who also is an architect of some note, has been struggling for nearly five years with the design of the memorial for President (and World War II general) Dwight D. Eisenhower in Washington, D.C. Last week, the proposal met with another setback, as a House appropriations committee eliminated funding for it as part of a proposed budget bill, but first, here’s a quick recap:

In 2009, Gehry won a competition organized by the Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial Commission (EMC), including the participation of Eisenhower's grandson David, with a proposal calling for large stone reliefs of Eisenhower surrounded by enormous metal "tapestries" depicting scenes from his childhood in Kansas. An initial concept was approved by the United States Commission of Fine Arts in September 2011 and construction was to begin in 2012. But a couple months later, David Eisenhower stepped down from the EMC and withdrew his support for the memorial. The Eisenhower family has been vocal in its opposition to the design, criticizing it for its focus on Eisenhower's childhood, the use and placement of the “tapestry,” among other reasons.

In May 2012, Gehry revised his design in response to public and congressional concerns, adding statues that celebrating Eisenhower as both a military leader and a political leader (traditional statues are often the first compromise in abstract memorials). Critics were not appeased, and the family began calling for a new competition. Problems and questions continued to plague the project; in April 2014, the National Capital Planning Commission voted not to approve the design, asking for amendments before consenting to further development of the project. The Eisenhower Memorial Commission, who have continued to support the project in spite of mounting costs and criticism, will present a variation on the plan in early September.

This is all standard operating procedure in Washington. There is a long history of memorial controversies, the most famous being Maya Lin's iconic Vietnam Memorial, but even the Jefferson Memorial stirred up trouble, as did the Franklin Delano Roosevelt memorial. This latter case in particular shares similarities with the Eisenhower project.

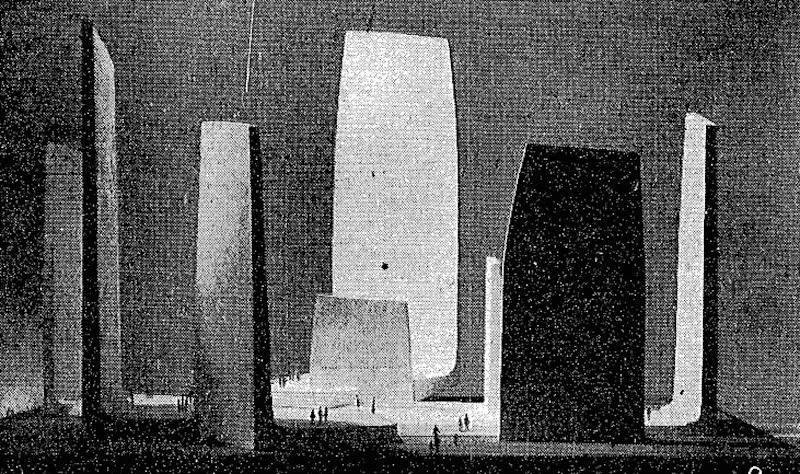

In 1959, the recently established Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial Commission launched a competition for the design of a memorial to commemorate the former president. From a field of nearly 600 submissions, the commission was awarded to New York architects Pedersen and Tilney, whose design called for eight building-sized concrete slabs engraved with quotations from Roosevelt’s speeches

It was a controversial choice, derided in the press as an “instant Stonehenge” and summarily rejected by, the public, the United States Commission of the Fine Arts, and by Roosevelt’s daughter Anna. After much debate, the architects were asked to revise their design, and in 1964, they resubmitted a scaled-down version of their Stonehenge that included the notable addition of a large statue of Roosevelt. Though it was approved by the Fine Arts Commission, now made up of all new members, the Roosevelt family expressed their strong objections and Congress, who also needed to approve the design, tabled the project. Undeterred, (well, maybe a little deterred), the Memorial Commission changed tactics: abandoning the winning design and the idea of an open competition, the Commission consulted with the American Institute of Architects and other professional organizations, interviewed five candidates -- Marcel Breuer, Philip Johnson, Paul Rudolph, E. Lawrence Bellante, and Andrew Euston -- and, in 1966, awarded the commission to Breuer.

As New York Times critic Ada Louise Huxtable noted at the time, the method of the appointment “aroused some criticism in professional circles.” But in retrospect it seems like an obvious choice. Breuer was hot off his Whitney Museum in New York and had previously experience working with the government, designing the United States embassy in The Hague, the Department of Housing and Urban Development, which at the time of his selection was under construction and under budget.

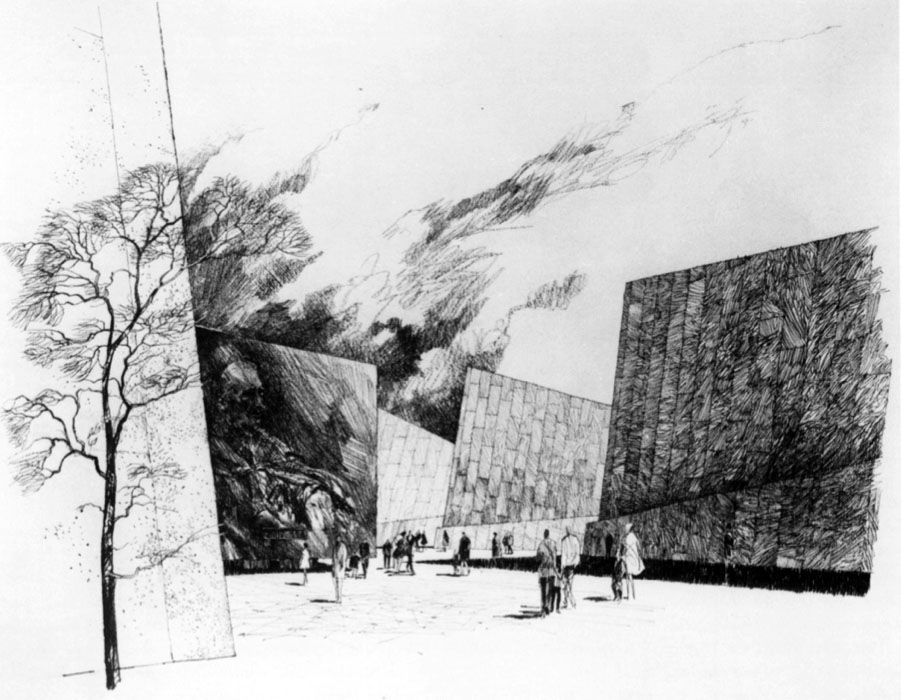

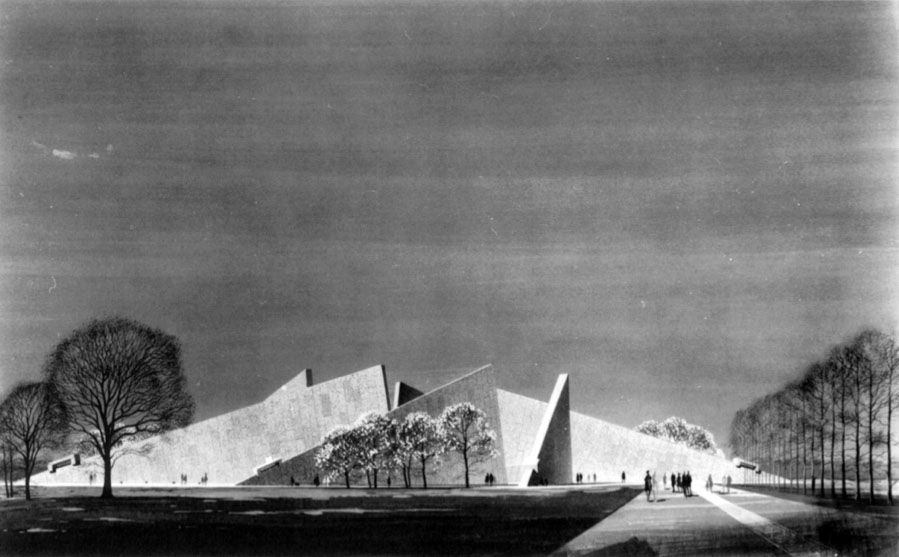

For any architect, no matter how talented, a memorial is a complex undertaking. It needs to celebrate an individual while also representing a nation’s collective unconscious. In Breuer’s view, Roosevelt was a modern man and only a modern memorial would do his memory justice. “He discovered and supported new solutions,” Breuer wrote in his proposal, “and it would perhaps be anachronistic to identify him in this Memorial by the usual idolizing statue.” His design was unveiled in December 1966 and immediately and unanimously approved by the FDR Memorial Commission and Franklin D. Roosevelt, Jr.

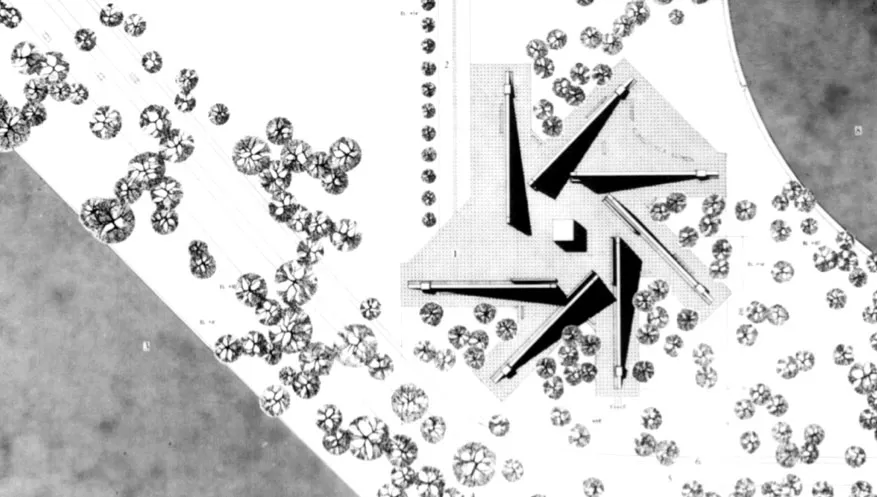

Like the rejected design from Pedersen & Co, Breuer’s abstract memorial design was sculpture at the scale of architecture. It consisted of 60-foot-high rough granite triangles--”stone darts,” as Breuer called them-- spiraling around a large, spinning, dark granite cube engraved with a half-tone portrait of the former President, along with hidden loudspeakers intended to commemorate Roosevelt’s innovative and inspiring radio broadcasts by playing excerpts from his most famous speeches. Huxtable called it “the most promising monument to loom on the memorial scene..in quite a while,” going on to call the scheme “a thoughtful, contemporary, creative solution that honors the man it commemorates at a representative level of today’s esthetic achievement, without doing violence to the classical Washington image.”

Unfortunately, the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts did not agree. In January 1967, Breuer’s design met with harsh and unexpected criticism from all the Commission members: artist William Walton, critic Aline B. Saarinen, architects Gordon Bunshaft and John Carl Warnecke, and sculptor Theodore Roszak. Calling it “coarse”, “unpleasant,” and “disrespectful”, the critics attacked the design for its lack of a focal point, the overwhelming scale of the project, and the gimmicky use of the canned recordings. Rather than creating a timeless design, Breuer had, in the the view of the Commission, created “pop art sculpture.”

Breuer kept his cool. After listening to the onslaught of criticism, he made a passionate speech explaining the concepts behind his design. It almost worked. The committee began to second-guess their initial assessment, causing Saarinen to wonder if indeed it would be possible to do anything better.

The reconsideration was short lived.

We know how this story ends. In 1974, a memorial designed by landscape architect Lawrence Halprin finally won approval, though it too was not without controversy. It took 20 years for construction to start but the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial was finally dedicated on May 2, 1997. Made up of four outdoor galleries tied together across seven-and-a-half acres with a meandering pathway and symbolic water features, the Halprin design tells the story of America during Roosevelt’s presidency through bronze sculptures and quotations carved into granite.

The Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial Commission is now planning to re-present their design in September. While they rework the proposal, lest it go the way of Breuer’s forgotten memorial, the architects might want to keep in mind these sound words of advice from Ada Louise Huxtable: "A monument stands for its age, as well as for a man. Those with the criteria to judge will question the greatness of both if the expressive medium of immortalization is mediocrity."

Sources:

- Bess Furman, “A Shrine Chose for Roosevelt,” The New York Times (December 31, 1960)

- Ada Louise Huxtable, “Breuer to Shape Roosevelt Shrine,” The New York Times (June 9, 1966)

- Ada Louise Huxtable, “If at First You Don’t Succeed,” The New York Times (January 1, 1967)

- Isabelle Hyman, “Marcel Breuer and the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 54, No. 4 (December, 1995): 446- 458

Editors' Note, July 23, 2014: This piece has been edited from its original version to clarify a variety of facts about the state of the proposed Eisenhower memorial. We regret the inaccuracies.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)