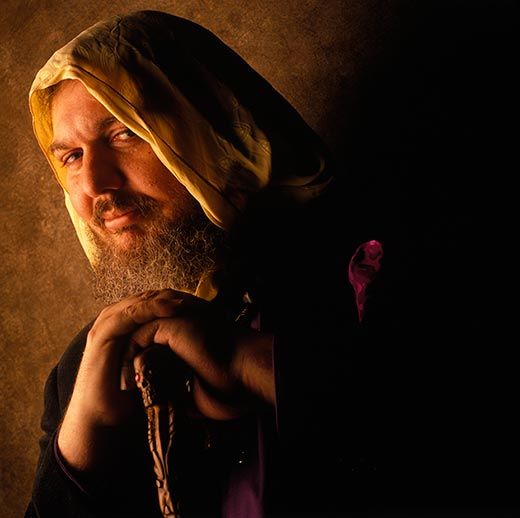

Dr. John’s Prognosis

The blues and rock musician shares stories of his wild past and his concerns for the future.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Mac-Rebennack-Dr-John-musician-631.jpg)

Mac Rebennack, better known as the musician Dr. John, has been impressing audiences since the 1960s with a stage show deeply rooted in the culture of his native New Orleans. In his heyday, Rebennack would appear on stage in a puff of smoke, decorated in Mardi Gras plumes, bones and amulets, reciting voodoo chants while spreading glitter into the audience. But he is also a highly regarded blues, rock and jazz artist considered a solid songwriter and session musician. In his most recent album, "The City that Care Forgot," he criticizes the government's response to Hurricane Katrina and plays with Eric Clapton, Willie Nelson and Ani Difranco. Rebennack, 68, spoke recently with Kenneth Fletcher about his wild past and concerns about the future

What kind of music did you hear growing up?

Well, my father's records were what they called "race records", which was blues, rhythm and blues, traditional jazz and gospel. He owned a record shop and had a large black clientele. They would come by and play a record to decide if they liked it. I got the idea as a little kid that I wanted to be a piano player, because I remember hearing [boogie woogie pianist] Pete Johnson. I thought why not just be Pete Johnson?

But I started playing guitar because I thought I'd never get a job playing piano. Every guitarist I knew could get work easy. Somewhere in the early ‘50s I started doing recording sessions and after that I went on the road.

How did you get back to playing piano?

Around 1960, I got shot in my finger before a concert. A guy was pistol whipping Ronnie Barron, our vocalist. Ronnie was just a kid and his mother had told me "You better look out for my son." Oh god, that was all I was thinking about. I tried to stop the guy, I had my hand over the barrel and he shot.

So you switched to piano because of the injury. You must have been playing some seedy places.

They were pretty much buckets of blood joints. It was not a wholesome atmosphere where you could bring your family along. There were gang fights. The security and the police would fire guns into the crowd. It was pretty wild.

Bourbon Street was always the touristy scene, but Canal Street, Jackson Avenue, Lasalle Street, Louisiana Avenue- all of them had strips of clubs on them. Later [New Orleans District Attorney] Jim Garrison padlocked and shut down the whole music scene.

What kind of music did you play?

All different kinds. At one gig we might be backing up strippers and playing Duke Ellington stuff. One girl might want flamenco or maybe belly dancing music. Then the next gig we would play pop and R&B songs of the day. Later there would be an after-hour jam session. It was pretty great. We worked 365 days a year, 12 hours a night, and did sessions during the day. I've always thought that my chops were a lot better then than they ever have been since.

How did you go from Mac Rebennack the backup musician, to becoming Dr. John?

I was never fond of front men. I didn't want to be one. All my plans were for Ronnie Barron, the same guy who I got shot in my finger over, to be Dr. John. Then my conga player said "Look, if Bob Dylan and Sonny and Cher can do it you can do it." He talked me into it. I did my first record to keep New Orleans gris gris alive.

The Dr. John character is based on gris gris, or voodoo?

Well yeah. I always thought it was a beautiful part of New Orleans culture. It's such a blend of stuff; African, Choctaw, Christianity, Spanish.

I just figured that if I wrote songs based on gris gris, it would help people. A lot of the people practicing it were dying off and the kids were not following it. I was trying to keep the traditions going.

Where did the name Dr. John came from?

If you go back in the historical records of New Orleans there was a guy in the 1800s that was named Dr. John. He was a free man of color, as they said in those days, and a gris gris man.

How would you describe voodoo?

It respects all religions, it respects everything. An old lady told me one time, "There's nothing wrong with any religion, it's just that man can mess up anything and make it into something very bad." It's true. It happens all the time.

Didn't you use voodoo chants into your songs?

I went up to some of the reverend mothers and I asked them could I do a sacred song. But I couldn't do them because it was not for a ceremony. So I wrote something similar.

One we used went "corn boule killy caw caw, walk on gilded splinters." It actually translates to cornbread, coffee and molasses in old Creole dialect. It's very connected to the real one that it's based on.

Can you describe your stage show as Dr. John?

We would wear large snakeskins, there was a boa constrictor, an anaconda, a lot of plumes from Mardi Gras Indians. We were trying to present a show with the real gris gris. We had a girl, Kolinda, who knew all of the great gris gris dances.

How did audiences react?

We did just fine, until we got busted one day in St. Louis for a lewd and lascivious performance and cruelty to animals. We would come out on stage wearing only body paint. Everywhere else that was cool, but not in St. Louis. We also had Prince Kiyama, the original chicken man. He would bite the head off the chicken and drink the blood.

Why?

When you offer a sacrifice in gris gris, you drink some of the blood. In church they would chant "Kiyama drink the blood, Kiyama drink the blood." I thought it would be really cool to add Prince Kiyama to the show. That was another one of my rocket scientifical ideas.

Prince Kiyama said, "If you are going to charge me with cruelty to chickens, arrest Colonel Sanders." It didn't go over well with the judge. I think the courts looked at it like we were dropping acid out the wazoo. Everybody thought we were part of the acid thing, but I don't think any of us did that.

Your latest album, The City that Care Forgot, criticizes the government's response to Hurricane Katrina.

None of my work has been as aggravated or disgusted as this record. I had never felt the way I do now, seeing New Orleans and the state of Louisiana disappearing. We've given the world jazz, our kind of blues, a lot of great food, a lot of great things. It's so confusing to look at things these days.

I'm concerned that much of the population of New Orleans is not there anymore. There were families split apart and just dumped across the country. A lot of people lost their homes, don't know where their loved ones are. I see them on the road all the time. These people have no idea how to live in Utah or wherever they are. Some have never left New Orleans and just don't know how to deal with it.

On the song Save Our Wetlands, you sing "we need our wetlands to save us from the storm"?

Our culture is getting hit from so many directions, like the oil companies cutting salt water canals that are destroying the wetlands in South Louisiana. Seeing that makes me feel horrible. There is more and more offshore oil drilling, and just so many stands of dead cypress trees. I'm just trying to tell the truth about stuff that nobody seems to wants to talk about. Really it gets me a little crazy.

Louisiana is a small state where corruption has been rampant for too long. The songs on this album came out of not knowing how else to get the message across. If we don't do what we can musically trying to help somebody, what are we here for?