Doodle Dandy

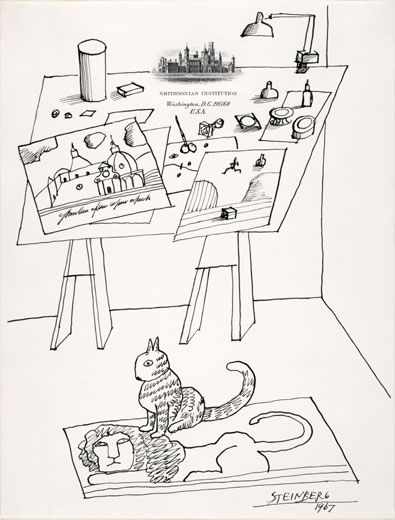

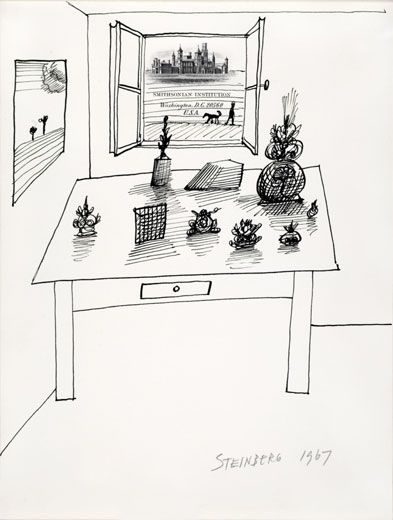

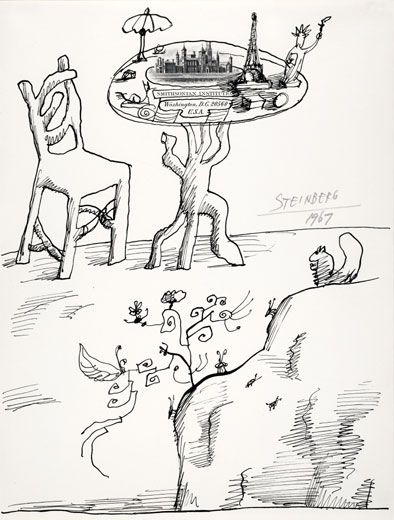

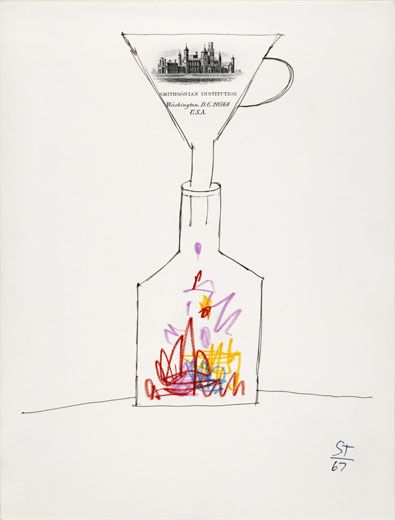

With a few deft strokes, Saul Steinberg turned institutional letterhead into signature works of whimsy

In 1967, then-Secretary of the Smithsonian S. Dillon Ripley invited Saul Steinberg to serve as the Institution's first and only artist-in-residence. The Romanian-born Steinberg, schooled in philosophy in Bucharest and architecture in Italy, had come to the United States in 1941 and quickly established himself as a graphic artist who merged Cubism, Surrealism and sly humor, particularly in elegant, imaginative drawings and covers for the New Yorker magazine. His style was at once simple and antic, serious and slapstick, metaphoric and mischievous.

In 1946, Steinberg was included in the now legendary "Fourteen Americans" show at the Museum of Modern Art, in the company of luminaries including sculptor Isamu Noguchi and painters Arshile Gorky and Robert Motherwell. Fellow graphic artist Milton Glaser says that Steinberg "could see the extraordinary nature of the banal in a way that you almost have to be an outsider to do."

The job description for the post—which included a then-generous stipend of $11,000—was imprecise; even the length of tenure was vague, although Steinberg, in a December 1965 letter to Ripley, spoke of staying "for at least 6 months or perhaps a whole year." In fact, the artist remained in town less than four months, working out of a comfortable rented town house rather than the office provided for him. A January 1967 Washington Star headline told the story: "Smithsonian's Steinberg: An Artist Not-in-Residence."

But despite this aloofness and a sincere dislike of Washington—a city Steinberg would later describe in the pages of this magazine as having "ready-made art, bland townhouses of Georgetown, goody-goody churches, a completely American kind of city planning"—the artist delivered fair value for Ripley's largesse.

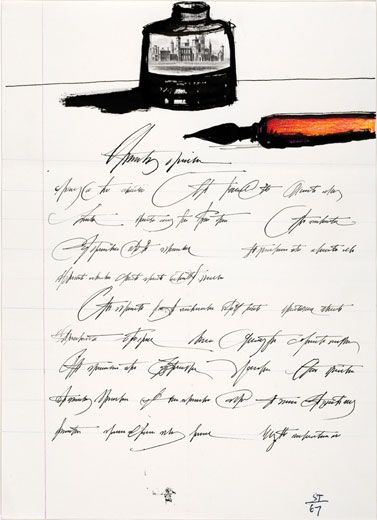

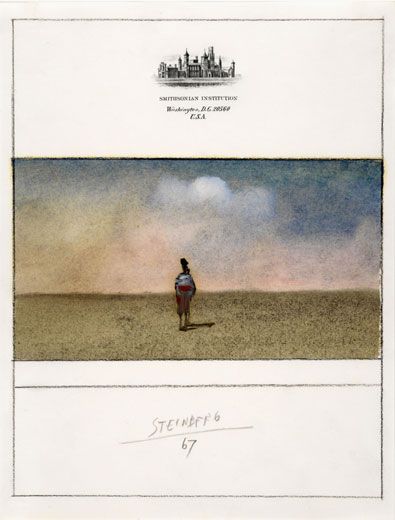

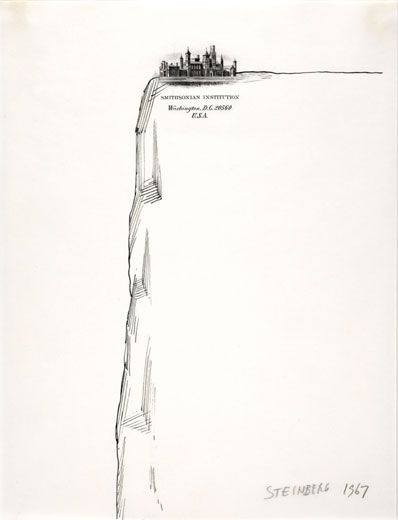

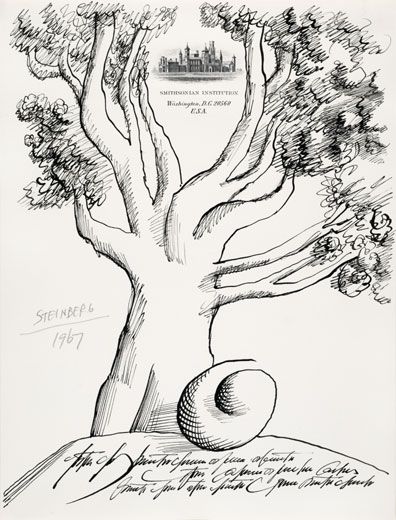

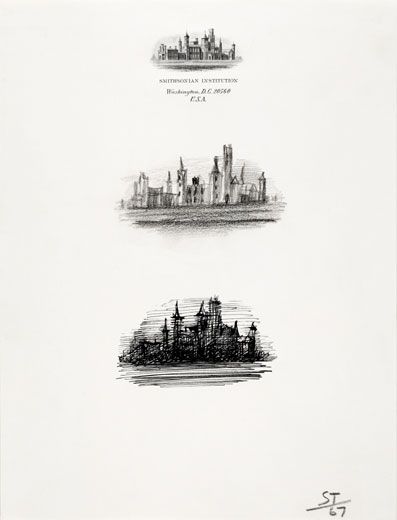

Steinberg drawings often incorporate found graphics such as official-looking seals and rubber stamps and coin rubbings, so it was pure serendipity that the Smithsonian letterhead at the time included an engraving of the Institution's signature building, the James Renwick-designed structure known to this day as the Castle. Steinberg had predicted that when he got to Washington, he would "feel my way along and decide then what to do." The solution was quickly at hand: the stationery would constitute his sketch pad, and the letterhead would become an integral element of each drawing. By the time the artist headed back home to New York City, he left behind, according to Joann Moser, a senior curator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM), a total of 36 drawings, "everything done on that stationery." Of the 36, the Smithsonian owns 29, of which 18 are on view in a traveling exhibition: "Saul Steinberg: Illuminations," organized by Vassar College, at SAAM through June 24.

In an extended riff, Steinberg incorporated the logo into sketches of subjects as various as teapots, a cluttered drafting table, a cliff edge, a cityscape of faceless government buildings, a dinner plate on a table and, as the crowning glory, the dog, dreaming of the Smithsonian Castle, shown here. The drawings represent a unique object lesson in how the imagination of a great artist can invent variations on a theme until...well, until he leaves the building.

Owen Edwards is a freelance writer and author of the book Elegant Solutions.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)