CSI: Italian Renaissance

Inside a lab in Pisa, forensics pathologist Gino Fornaciari and his team investigate 500-year-old cold cases

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Italian-Renaissance-female-skeleton-631.jpg)

High on the facade of Santa Maria Antica, among soaring Gothic spires and forbidding statues of knights in armor, pathologist Gino Fornaciari prepared to examine a corpse. Accompanied by workmen, he had climbed a 30-foot scaffold erected against this medieval church in Verona, Italy, and watched as they used hydraulic jacks to raise the massive lid of a marble sarcophagus set in a niche. Peering inside, Fornaciari found the body of a male in his 30s, wearing a long silk mantle, arms crossed on his chest. The abdomen was distended from postmortem putrefaction, although Fornaciari caught no scent of decomposition, only a faint waft of incense. He and the laborers eased the body onto a stretcher and lowered it to the ground; after dark, they loaded it into a van and drove to a nearby hospital, where Fornaciari began a series of tests to determine why the nobleman died—and how he had lived.

The victim, it appeared, had suffered from several chronic and puzzling conditions. A CT scan and digital X-ray revealed a calcification of the knees, as well as a level of arthritis in elbows, hips and lumbar vertebrae surprisingly advanced for anyone this young. A bronchoscopy showed severe anthracosis, similar to black lung, although he hadn’t been a miner, or even a smoker. Histological analysis of liver cells detected advanced fibrosis, although he had never touched hard liquor. Yet Fornaciari, a professor in the medical school at the University of Pisa, saw that none of these conditions likely had killed him.

Of course, Fornaciari had heard rumors that the man had been poisoned, but he discounted them as probable fabrications. “I’ve worked on several cases where there were rumors of poisonings and dark plots,” Fornaciari told me later. “They usually turn out to be just that, mere legends, which fall apart under scientific scrutiny.” He recited the victim’s symptoms in Latin, just as he had read them in a medieval chronicle: corporei fluxus stomachique doloris acuti . . . et febre ob laborem exercitus: “ diarrhea and acute stomach pains, belly disturbances . . . and fever from his labors with the army.”

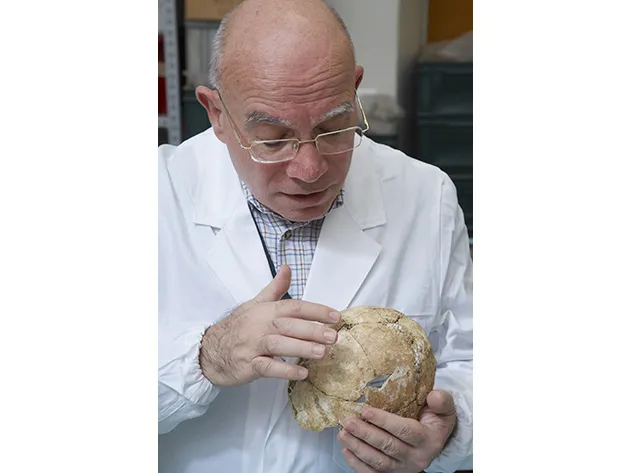

Gino Fornaciari is no ordinary medical examiner; his bodies represent cold cases that are centuries, sometimes millennia, old. As head of a team of archaeologists, physical anthropologists, historians of medicine and additional specialists at the University of Pisa, he is a pioneer in the burgeoning field of paleopathology, the use of state-of-the-art medical technology and forensic techniques to investigate the lives and deaths of illustrious figures of the past.

Its practitioners worldwide are making startling discoveries. In December 2012, a team of scientists published results from an examination of the mummy of Pharaoh Ramses III, showing that he had died from having his throat slit, likely murdered in the so-called “harem conspiracy” of 1155 B.C. This May, Smithsonian anthropologist Douglas Owsley said he’d found evidence of cannibalism at Virginia’s Jamestown Colony, probably in the winter of 1609; cut marks on the skull and tibia of a newly exhumed 14-year-old girl’s remains indicated that her brain, tongue, cheeks and leg muscles were removed after her death. Scholars have reconstructed the faces of Renaissance figures including Dante and St. Anthony of Padua based on remains of their crania (Petrarch’s head, it emerged, had been swapped out at some point with that of a young woman). They are currently sifting the subsoil of a Florentine monastery for remains of Lisa Gherardini, a noblewoman believed by some art historians to be the model Leonardo da Vinci used when he painted the Mona Lisa.

But no one has made more important and striking finds than Gino Fornaciari. Over the past half-century, using tools of forensics and medical science as well as clues from anthropology, history and art, he and his colleagues have become detectives of the distant past, exhuming remains throughout Italy to scrutinize the lives and deaths of kings, paupers, saints, warriors and castrati opera stars. Fornaciari himself has examined entire noble populations, including the Medici of Florence and the royal Aragonese dynasty of Naples, whose corpses have been, in effect, archives containing unique clues to the fabric of everyday life in the Renaissance.

Such work is not without its critics, who brand scholars such as Fornaciari as little more than grave-robbers, rejecting their efforts as a pointless, even prurient, disturbance of the dead’s eternal rest. Yet paleo-sleuthing has demonstrated its value for the study of the past and future. As Fornaciari has solved some of history’s oldest riddles and murder mysteries, his work also holds life-and-death relevance. By studying modern killers such as malaria, tuberculosis, arteriosclerosis and cancer, whose telltale signs Fornaciari has found in ancient cadavers, he is helping to understand the origins of diseases and to predict the evolution of pathologies. “Gino Fornaciari and his team are prime movers in the field,” says bioarchaeologist Jane Buikstra of Arizona State University, author of The Global History of Paleopathology. “They’re shaping paleopathology in the 21st century and enriching discussion in a range of other fields, too.”

Fornaciari’s current “patient,” the nobleman interred at Santa Maria Antica, was Cangrande della Scala, warlord of Verona, whose family ruled the city and a swath of northeastern Italy with an iron hand seven centuries ago. They reigned at the beginning of the Italian Renaissance, that blaze of artistic creativity and new self-awareness that illumined the end of the Middle Ages and permanently altered human consciousness. Cangrande was a paradigmatic Renaissance man: Giotto painted his portrait, the poet Boccaccio celebrated his chivalry and Dante lauded him lavishly in the Paradiso as a paragon of the wise leader.

In July 1329, he had just conquered the rival town of Treviso and entered the city walls in triumph when he fell violently ill. Within hours he was dead. Several medieval chroniclers wrote that, shortly before his conquest, Cangrande had drunk at a poisoned spring, but Fornaciari doubted this hypothesis. “I’m always skeptical about claims of poisoning,” Fornaciari says. “Since Cangrande died in the summer, with symptoms including vomiting and diarrhea, I originally suspected that he’d contracted some sort of gastrointestinal disease.”

The answer to the puzzle was contained in Cangrande’s body, naturally mummified in the dry, warm air of his marble tomb, making it a treasure trove of information on Renaissance existence. His pathologies, unfamiliar today, made perfect sense for a 14th-century lord and warrior on horseback. The curious arthritis visible in Cangrande’s hips, knees, elbows and sacro-lumbar region indicates what Fornaciari terms “knightly markers,” disorders developed by cavalrymen during a lifetime in the saddle, wielding weighty weapons such as lances and broadswords. His liver disease may well have been caused by a virus, not alcohol, because hard liquor was unknown in Cangrande’s day. The knight’s respiratory ailments were likewise linked to life in a world lighted and warmed by fire, not electricity. Torch-lit banquet halls and bedchambers, where chimneys became widespread only a century later, and the smoky braziers used in army tents while on campaign, caused the kind of lung damage that today could be found in coal miners.

Strangest of all, however, were the results of pollen analysis and immunochemical tests conducted on Cangrande’s intestines and liver. Fornaciari isolated pollen from two plants: Matricaria chamomilla and Digitalis purpurea. “Chamomile,” he told me, “was used as a sedative; Cangrande could have drunk it as a tea. But foxglove? That shouldn’t have been there.” The plant contains digoxin and digitoxine, two potent heart stimulants, which in doses like those detected in Cangrande’s body can cause cardiac arrest. During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, foxglove was used as a poison.

In fact, the symptoms mentioned by contemporary chroniclers—diarrhea, stomach pains and fever—matched those of digoxin and digitoxine poisoning. Hence, Fornaciari concluded, Cangrande had been murdered. As it happens, a contemporary chronicler reported that a month after Cangrande’s death, one of the nobleman’s doctors had been executed by Mastino II, Cangrande’s successor, suggesting the doctor’s possible involvement in a plot to kill his master. Who ultimately was responsible for the murder remains a mystery—an assertive fellow like Cangrande had plenty of enemies—although the ambitious Mastino II himself now emerges as a prime suspect.“I thought the poisoning story was just a legend, but sometimes the legends are true,” Fornaciari says. “Paleopathology is rewriting history!”

***

Fornaciari trained as a medical doctor, and when I met him in his office at the department of oncology at the University of Pisa, he was applying his expertise to the present, peering through a microscope at samples from biopsies performed at the nearby university hospital. “I have to distinguish benign from malignant tissues,” he said, nodding to trays of samples stacked beside the microscope. “I have to be right, or there could be serious consequences for the patient—a surgeon could remove a healthy lung or breast, or leave a deadly malignancy in place.”

Now age 70, Fornaciari is an exemplar of that by now endangered species, the Italian university professor of the old school, who combines an almost fin de siècle formality with personal warmth and a disarming passion for his work. The son of factory workers in Viareggio, a coastal town near Pisa, Fornaciari earned his M.D. at the University of Pisa in 1971. He’s always been fascinated with the past, and from the outset of his medical training made forays into the health, quality of life and lifestyles of distant eras. During medical training he also took courses in archaeology and participated in excavations of prehistoric and Etruscan sites throughout Tuscany. In the early 1980s, the center of gravity of Fornaciari’s work began to shift from present to past, as he joined Vatican researchers charged with examining the remains of several prominent saints, including Pope Gregory VII and St. Anthony of Padua.

In 1984, Fornaciari agreed to lead an investigation of the most significant noble remains then to have been exhumed in Italy, the 38 naturally and artificially mummified bodies of the Aragonese royal family of Naples—major figures in the Italian Renaissance, buried in the Neapolitan basilica of San Domenico Maggiore. Fornaciari began to collaborate with scholars in Pisa and across Italy, who coalesced into an interdisciplinary team centered in Pisa. His investigators, here and in other parts of Italy, range from archaeologists to parasitologists and molecular biologists.

“Gino recognizes the fundamental importance of historical documentation and context in ways that I haven’t seen anyone else do,” says Clark Spencer Larsen of Ohio State University, a physical anthropologist who, with Fornaciari, co-directs a field project in Badia Pozzeveri, a medieval monastery and cemetery near Lucca. “He’s knowledgeable in many other areas as well. He’s pragmatic and interested in whatever answers the question, ‘How are we going to figure this out?’”

By now, Fornaciari had become the go-to guy for old bones in Italy, and was tackling an ever-growing range of centuries-old corpses, including an entire community overwhelmed by the Black Plague in Sardinia, and a cache of 18th- and 19th-century mummies in an underground crypt in northeastern Sicily. Then, in 2002, he and his team struck the mother lode of paleopathology when they were invited by the Italian minister of culture to investigate the 49 graves in the Medici Chapels in Florence, one of the most significant exhumation projects ever undertaken. Fornaciari still leads the ongoing investigation.

***

Recently, I drove out to visit his main paleopathology laboratory, established by the University of Pisa with a grant from the Italian Ministry of Research Institute. The structure is housed in a former medieval monastery, set on a hillside ringed by olive trees east of Pisa. When we arrive, a half-dozen researchers in lab coats are measuring human bones on marble tabletops, victims of a virulent cholera epidemic that ravaged Tuscany in 1854 and 1855, and entering anatomical data into a computer database. At another counter, two undergraduates apply glue to piece together the bones of medieval peasants from a cemetery near Lucca.

Fornaciari explains the procedures used to solve historical puzzles. Researchers begin with a basic physical exam of bones and tissues, using calipers and other instruments. At the same time, he says, they create a context, exploring the historical landscape their subjects inhabited, consulting scholars and digging into archival records. For the past 15 years, they’ve used conventional X-ray and CT imaging at a nearby hospital to examine tissues and bones; conducted histological exams similar to those Fornaciari applies to living patients for a better understanding of tumors and other abnormalities; and relied on an electron microscope to examine tissues. More recently, they’ve employed immunological, isotopic and DNA analysis to coax additional information from their samples.

Work is done at many locations—here and at Fornaciari’s other Pisa laboratory, and in university labs throughout Italy, particularly Turin and Naples, as well as in Germany and the United States. On occasion, when examining illustrious, difficult-to-move corpses such as Cangrande della Scala or the Medici, Fornaciari cordons off an area of a church or chapel as an impromptu laboratory, creating kind of a field hospital for the dead, where he and his fellow researchers work under the gaze of curious tourists.

The laboratory, stacked with human bones, could easily seem grim— a murderer’s cave, a chamber of horrors. Instead, with its immaculate order and faint dry cedar-like scent, its soft bustle of conversation, this is a celebration of living. In the final analysis, it’s a laboratory of human experience, where anatomical investigation mingles with evidence from medicine, biography and portrait paintings to resurrect fully fledged life stories.

***

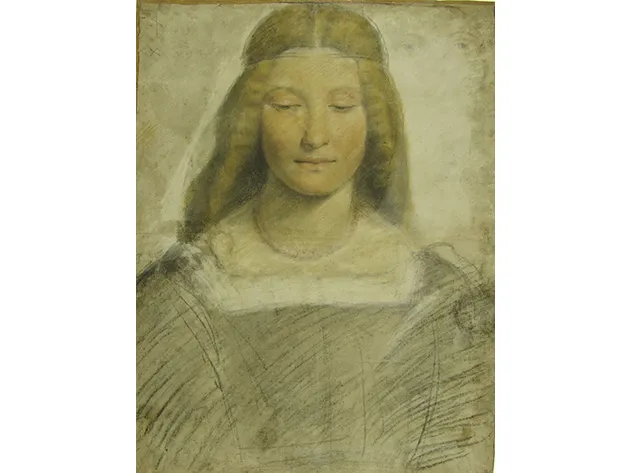

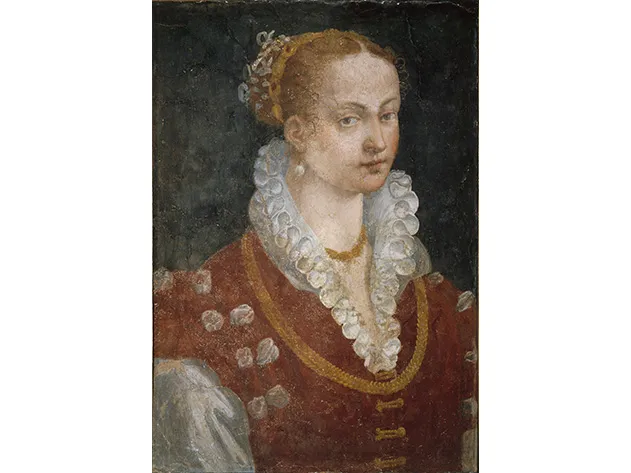

Some of the most compelling tales surround the dynasties of the Aragonese and Medici. Among Fornaciari’s most memorable “patients” is Isabella of Aragon, born in 1470, a shining star at the greatest courts of Italy, renowned for her intellect, beauty, courage in battle and remarkable fortitude. She knew Leonardo da Vinci; some art historians also believe she could have been the model for the Mona Lisa. She conducted famous love affairs with courtier Giosuè di Ruggero and condottiero Prospero Colonna, as well as, one scholar maintains, with Leonardo himself. Even an objective scientist such as Fornaciari isn’t immune to her charms. “Knowing that I had Isabella of Aragon in my laboratory, one of the most celebrated ladies of the Renaissance, who’d known Leonardo da Vinci—he’d made the magnificent theater backdrops for her wedding feast— all this raised certain emotions.”

All the more so when Fornaciari took a close look at Isabella’s teeth. The outer surfaces of those in the front of her mouth had been carefully filed—in some cases the enamel had been completely removed—to erase a black patina that still covered the teeth farther back. Electron microscopy revealed parallel striations on the front teeth, indicating abrasions made by a file. The black stain, it turned out, resulted from ingestion of mercury, in her day believed to combat syphilis. Proud Isabella, jealous of her celebrated beauty, had been attempting to hide the growing discoloration associated with her disease. “I imagine poor Isabella trying to preserve her privacy, not wanting to appear with black teeth because people would know she had venereal disease,” says Fornaciari.

His examination of Isabella’s grandfather, Ferrante I, King of Naples, born in 1431, also produced significant results. This great lord presided over a literary salon where leading humanist scholars converged, but he was also a gifted warrior, who with astuteness, courage and calculated—or, as his critics said, sadistic—savagery, maintained the independence of his kingdom against powerful enemies, both foreign and internal. No less a figure than Lorenzo the Magnificent de’ Medici traveled to Naples to kneel in submission before him. Ferrante died in 1494 at the age of 63, celebrated by contemporaries for maintaining his intellectual and physical vigor to the end of his life, although portraits completed during his later years showed that he had put on weight and occasionally appeared to be in pain.

Fornaciari debunked the myth of Ferrante’s enduring good health. Although the king’s mummified body had been lying in its cedar coffin for five centuries, and in 1509 had been badly damaged by a fire in the basilica, Fornaciari managed to recover a segment of Ferrante’s intestine, which when rehydrated showed a pattern of yellowish spots that looked sinisterly familiar to him from analyses of modern biopsies. Extracting DNA from mummified tissue, Fornaciari found mutation in the K-ras gene—clear proof that Ferrante had suffered from advanced colon cancer, most probably a colorectal adenocarcinoma. Fornaciari had made medical history, by identifying an oncogene mutation in an ancient tumor; his results offer potentially important data for studying the evolution of the disease.

Fornaciari subsequently analyzed bone collagen of King Ferrante and other Aragonese nobles, revealing a diet extremely reliant on red meat; this finding may correlate with Ferrante’s cancer. Red meat is widely recognized as an agent that increases risk for mutation of the K-ras gene and subsequent colorectal cancer. (As an example of Ferrante’s carnivorous preferences, a wedding banquet held at his court in 1487 featured, among 15 courses, beef and veal heads covered in their skins, roast ram in a sour cherry broth, roast piglet in vinegar broth and a range of salami, hams, livers, giblets and offal.)

Maria of Aragon, another famous beauty of the Renaissance, noted for her proud, fiery temperament, whose intellectual circle included Michelangelo, was found to have syphilitic lesions and human papillomavirus (HPV). Fornaciari’s identification of the latter in an ancient cadaver also offered new clues to the evolution of the virus.

King Ferrante II, who died young and surpassingly handsome at 28, shortly after the great Carpaccio painted his portrait, was found to have head lice, as well as poisoning from the mercury he used in an attempt to vanquish the infestation. An anonymous, richly dressed member of the Aragon family, about 27 years of age, had a fatal dagger wound in his left side, between the eighth and ninth ribs, with signs of massive bleeding.

Fornaciari also studied electron micrographs of tissue samples from an anonymous 2-year-old Aragonese child who died around 1570. He observed the lethal smallpox virus—which reacted to smallpox antibodies after centuries in the grave. Concerned that the virus could still be infectious, the Italian Ministry of Health threatened to close Fornaciari’s lab and impound the tiny cadaver, until Fornaciari reported that he had already sent samples for testing to the United States and Russia, where specialists pronounced the smallpox DNA biologically inert and therefore harmless.

***

Fornaciari uncovered some of his most moving and detailed personal stories during exhumations of the Medici, begun in 2003. A driving force in the artistic, intellectual and economic life of the Italian Renaissance, the noble house helped to establish Florence as the cultural center of the Western world. The Medici were the patrons of Brunelleschi, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Botticelli and Galileo Galilei. “You can’t really remain indifferent to someone like Cosimo I de’ Medici, one of the architects of the Renaissance,” Fornaciari says. An inexperienced teenager who suddenly came to power in Florence in 1537, Cosimo rescued the city-state of Florence, turning a foundering republic at the mercy of foreign powers into an independent duchy that was once more a major player on the European stage. He founded the Uffizi Gallery, freed Florentine territories from foreign armies and built a navy, which was instrumental in preventing the Ottoman takeover of the Mediterranean Sea during the Battle of Lepanto in 1571.

The wealth of biographical information available on Cosimo I allowed Fornaciari to synthesize contemporary testimony and forensic investigation. Documentation concerning Cosimo and his descendants is some of the most extensive in early modern history—the online database of the Medici Archive Project contains descriptions of some 10,000 letters and biographical records on more than 11,000 individuals. Portraits of Cosimo I in museums around the world depict his evolution from a shy, seemingly wary youth in 1538 to a bearded warrior in a polished suit of armor in 1565, and an elderly, corpulent and world-weary figure, gazing absently into space, toward the end of his life in 1574. Reports by court physicians and foreign ambassadors to the Florentine duchy recount Cosimo’s medical history in excruciating detail: He survived smallpox and “catarrhal fever” (likely pneumonia) in youth; suffered in later life from paralysis of his left arm, mental instability and incontinence; and had a painful condition of the joints described by contemporaries as gout.

Fornaciari found that Cosimo’s remains indicated he had been an extremely robust and active man, in whom Fornaciari also noted all of the “knightly markers”—sacro-lumbar arthritis, hypertrophy and erosion of certain parts of the femur, rotation and compression of the upper femur, and other deformations—typical of warriors who rode into battle on horseback. He noted nodes between Cosimo’s vertebrae, signs that as an adolescent, the young duke had worn heavy weights over his thorax, most probably suits of armor. Fornaciari also noticed pervasive arthritis and ossification between the sixth, seventh and eighth thoracic vertebrae, possible signs of diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH), a disease of the elderly linked to diabetes. “We see Cosimo getting fatter in his portraits, and the presence of DISH suggests he may have had diabetes, too,” says Fornaciari. “The diet of the Medici and other upper-class families often contained many sweets, which were a sort of status symbol, but often caused health problems.”

Another vivid marker was Cosimo’s poor dental health. The right side of his mandible is marred by an enormous gap, the result of a serious periodontal disease; an abscess had eaten away his first molar and a considerable chunk of bone, leaving a massive crater in his jaw. Fornaciari’s examination of the Medici, the Aragonese and other high-born individuals has revealed appalling abscesses, decay and tooth loss, bringing home just how painful daily life in that period could be, even for the rich and famous.

Cosimo’s wife, Eleanora of Toledo, was the daughter of the Spanish viceroy of Naples and related to the Hapsburg and the Castilian royal families. Her face was immortalized by the Renaissance master Bronzino, who in a series of portraits captures her transformation from a radiant, aloof young bride to a sickly, prematurely aged woman in her late 30s, shortly before her death at age 40. Fornaciari uncovered the maladies that beset her. Dental problems plagued her. Slightly curved legs indicated a case of rickets she had suffered as a child. Childbirth had taken a major toll. “Pelvic skeletal markers show that she had numerous births—in fact, she and Cosimo had 11 children,” Fornaciari says. “She was almost constantly pregnant, which would have leached calcium out of her body.” Further analysis indicated that Eleanora had suffered from leishmaniasis, a parasitic disease spread by biting sand flies that can cause skin lesions, fever and damage to the liver and spleen. DNA testing also revealed the presence of tuberculosis. “She was wealthy, and powerful, but her life was brutally hard,” Fornaciari says.

***

Ultimately, Fornaciari also dispelled murder allegations directed against one of Cosimo and Eleanora’s sons. On September 25, 1587, Cardinal Ferdinando de’ Medici, second surviving son of Cosimo I and Eleanora of Toledo, visited his elder brother Francesco I in the opulent Medici villa in Poggio a Caiano, in the countryside near Florence. The brothers had been on bad terms for years, their relations poisoned by ambition and envy: Cardinal Ferdinando resented the fact that the coveted ancestral title, Grand Duke of Tuscany, had gone to Francesco after Cosimo’s death, and violently disliked his new sister-in-law, Bianca Cappello. Her young son Antonio, fathered by Francesco and legitimized when the couple had married, seemed likely to inherit the throne eventually. This gathering seemed a chance to mend bridges between the brothers and restore family peace.

Shortly after the cardinal’s arrival, Francesco and Bianca fell ill with ominous symptoms: convulsions, fever, nausea, severe thirst, gastric burning. Within days they were dead. Cardinal Ferdinando buried his brother with great pomp (Bianca was interred separately) and banished his nephew Antonio to a golden exile—whereupon Ferdinando crowned himself the new Grand Duke of Tuscany.

Rumors spread swiftly that the couple had been murdered. Cardinal Ferdinando, some whispered, had cleared his path to the ducal throne by killing the couple with arsenic, often preferred by Renaissance poisoners because it left no obvious traces on its victims. Others said that Bianca herself had baked an arsenic-laced cake for her detested brother-in-law, which her husband had tasted first by mistake; overcome with horror, Bianca supposedly ate a slice of the deadly confection as well, in order to join her beloved Francesco in the grave. A cloud of foul play enshrouded the unfortunate pair for centuries.

In 2006, four medical and forensic researchers from the University of Florence and the University of Pavia, led by toxicologist Francesco Mari, published an article in which they argued that Francesco and Bianca had died of arsenic poisoning. In the British Medical Journal, they described collecting tissue samples from urns buried beneath the floor of a church in Tuscany. At that church, according to an account from 1587 recently uncovered in an Italian archive, the internal organs of Francesco and Bianca, removed from their bodies, had been placed in terra-cotta receptacles and interred. The practice was not uncommon. (Francesco is buried in the Medici Chapels in Florence; Bianca’s grave has never been found.) Mari contended that the tissue samples—in which concentrations of arsenic he deemed lethal were detected—belonged to the grand duke and duchess. The rumors, argued the researchers, had been correct: Cardinal Ferdinando had done away with Francesco and his bride.

Fornaciari dismantled this thesis in two articles, one in the American Journal of Medicine, both of which showcased his wide-ranging skills as a Renaissance detective. Tissue samples recovered from the urns were likely not from the doomed Medici couple at all, he wrote. Those samples, he added, could have belonged to any of hundreds of people interred in the church over the centuries; in fact, the style of two crucifixes found with the urns attributed to Francesco and Bianca dates from more than a century after their deaths.

Even had the tissues come from the couple—which Fornaciari strongly doubts—he argued that the levels of arsenic detected by Mari were no proof of murder. Because arsenic preserves human tissue, it was routinely used in the Renaissance to embalm corpses. Since the couple’s bodies had certainly been embalmed, it would have been surprising not to have discovered arsenic in their remains. Fornaciari added that since Francesco was a passionate alchemist, arsenic in his tissues could well have come from the tireless experiments he performed in the laboratory of his palace in Florence, the Palazzo Pitti.

As a coup de grâce, Fornaciari analyzed bone samples from Francesco, showing that at the time of death he had been acutely infested with plasmodium falciparium, the parasitic protozoan that causes pernicious malaria. Fornaciari observed that malaria had been widespread in the coastal lowlands of Tuscany until the 20th century. In the three days before they fell ill, Francesco and Bianca had been hunting near Poggio a Caiano, then filled with marshes and rice paddies: a classic environment for malarial mosquitoes. He pointed out that the symptoms of Francesco and Bianca, particularly their bouts of high fever, matched those of falciparium malaria, but not arsenic poisoning, which does not produce fever.

***

Virtually anyone working in the public eye in Italy for long may run into la polemica—violent controversy—all the more so if one’s research involves titanic figures from Italy’s storied past. The recent row over a proposed exhumation of Galileo Galilei offers a prime example of the emotions and animus that Fornaciari’s investigations can stir up. In 2009, on the 400th anniversary of the great astronomer’s first observations of heavenly bodies with a telescope, Paolo Galluzzi, director of Florence’s Museo Galileo, along with Fornaciari and a group of researchers, announced a plan to examine Galileo’s remains, buried in the basilica of Santa Croce in Florence. They aimed, among other things, to apply DNA analysis to Galileo’s bone samples, hoping to obtain clues to the eye disease that afflicted Galileo in later life. He sometimes reported seeing a halo around light sources, perhaps the result of his condition.

Understanding the source of his compromised vision could also elucidate errors he recorded. For instance, Galileo reported that Saturn featured a pronounced bulge, perhaps because his eye condition caused him to perceive the planet’s rings as a distortion. They also planned to examine Galileo’s skull and bones, and to study the two bodies buried alongside the great astronomer. One is known to be his devoted disciple Vincenzo Viviani and the other is believed, but not confirmed, to be his daughter Maria Celeste, immortalized in Dava Sobel’s Galileo’s Daughter.

Reaction to the plan was swift and thunderous. Scholars, clerics and the media accused the researchers of sensationalism and profanation. “This business of exhuming bodies, touching relics, is something to be left to believers because they belong to another mentality, which is not scientific,” editorialized Piergiorgio Odifreddi, a mathematician and historian of science, in La Repubblica, a national newspaper. “Let [Galileo] rest in peace.” The rector of Santa Croce called the plan a carnivalata, meaning a kind of carnival stunt.

The plan to exhume Galileo is on hold, although Fornaciari remains optimistic that critics eventually will understand the validity of the investigation. “I honestly don’t know why people were so violently, so viscerally against the idea,” he says. He seems stunned and disheartened by the ruckus he’s kicked up. “Even some atheists had reactions that seemed to reveal decidedly theistic beliefs, akin to taboos and atavistic fears of contact with the dead. Surely they must see this isn’t a desecration. And we wouldn’t be disturbing his last rest—we could even help restore his remains, after the damage they undoubtedly suffered in the great flood of 1966 that hit Florence.”

It’s as if he is summing up his entire life’s work when he adds quietly: “Investigating that great book of nature that was Galileo would hardly harm his fame. On the contrary, it would enrich our knowledge of Galileo and the environment in which he lived and worked.”