Crop Circles: The Art of the Hoax

They may not be evidence of UFOs, ancient spirits or secret weapons, but there is something magical in their allure

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/crop-circles-631.jpg)

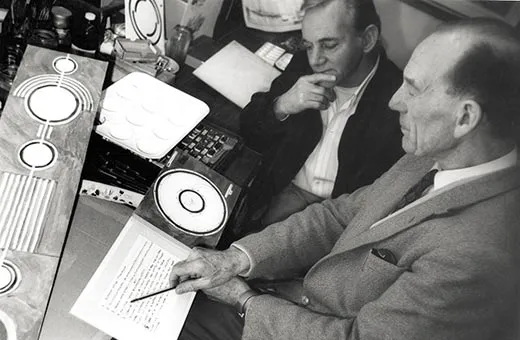

When Doug Bower and his co-conspirator Dave Chorley first created a representation of a “flying saucer nest” in a wheat field in Wiltshire, England, in 1976, they could not have foreseen that their work would become a cultural phenomenon.

Almost as soon as crop circles became public knowledge, they attracted a gaggle of self-appointed experts. An efflorescence of mystical and magical thinking, scientific and pseudo-scientific research, conspiracy theories and general pandemonium broke out. The patterns stamped in fields were treated as a lens through which the initiated could witness the activity of earth energies and ancient spirits, the anguish of Mother Earth in the face of impending ecological doom, and evidence of secret weapons testing and, of course, aliens. Today, one of the more vigorously promoted ideas is that they are messages, buried in complex numerological codes, concerning a Great Change connected to the pre-Columbian Mayan calendar and due to occur in 2012.

To appreciate how these exotic responses arose, we need to delve a little into history. Before today’s circle-makers entered the picture, there had been scattered reports of odd patterns appearing in crops, ranging from 17th century pamphlets to an 1880 account in Nature to a letter from astronomer Patrick Moore printed in 1963 in New Scientist. In Australia, the mid- to late-1960s saw occasional reports of circles in crops, and they were often ascribed to UFO landings. At around the same time in England, the Wiltshire town of Warminster became a center of UFO-seeking “sky watches” and gave birth to its own rumors of crop circles, or “saucer nests.” None of these, unfortunately, was photographed.

It was such legends that Bower had in mind when, over a drink one evening in 1976, he suggested to his pal Chorley: “Let’s go over there and make it look like a flying saucer has landed.” It was time, thought Doug, to see a saucer nest for himself.

Since then, crop circles have been reported worldwide in a multitude of crops. In southern England, which sees most activity, circle-makers tend to concentrate on canola, barley and wheat. These grow and are harvested in an overlapping progression: canola from April through May, barley throughout May and June, and wheat from June until early September. In recent years the occasional rudimentary pattern has been found in corn, extending the crop circle season as late as October. Since Bower and Chorley’s circles appeared, the geometric designs have escalated in scale and complexity, as each year teams of anonymous circle-makers lay honey traps for New Age tourists.

A crucial clue to the circles’ allure lies in their geographical context. Wiltshire is the home of Stonehenge and an even more extensive stone circle in the village of Avebury. The rolling downs are dotted with burial mounds and solitary standing stones, which many believe to be connected by an extensive network of “leys,” or paths of energy linking these enchanted sites with others around the country. It is said that this vast network is overlaid in the form of “sacred geometries.” The region has also given rise to a rich folklore of spectral black dogs, headless coachmen and haunted houses.

Crop circles are a lens through which we can explore the nature and appeal of hoaxes. Fakes, counterfeits and forgeries are all around us in the everyday world—from dud $50 bills to spurious Picassos. People’s motives for taking the unreal as real are easily discerned: we trust our currency, and many people would like to own a Picasso. The nebulous world of the anomalous and the paranormal is even richer soil for hoaxers. A large proportion of the population believes in ghosts, angels, UFOs and ET visitations, fairies, psychokinesis and other strange phenomena. These beliefs elude scientific examination and proof. And it’s just such proof that the hoaxer brings to the table for those hungry for evidence that their beliefs are not deluded.

False evidence intended to corroborate an existing legend is known to folklorists as “ostension.” This process also inevitably extends the legend. For, even if the evidence is eventually exposed as false, it will have affected people’s perceptions of the phenomenon it was intended to represent. Faked photographs of UFOs, Loch Ness monsters and ghosts generally fall under the heading of ostension. Another example is the series of photographs of fairies taken by Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths at Cottingley, Yorkshire, between 1917 and 1920. These show that the motive for producing such evidence may come from belief, rather than from any wish to mislead or play pranks. One of the girls insisted till her dying day that she really had seen fairies—the manufactured pictures were a memento of her real experience. And the photos were taken as genuine by such luminaries as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle—the great exponent, in his Sherlock Holmes stories, of logic.

The desire to promote evidence of anomalous and paranormal events as genuine springs from deep human longings. One is a gesture toward rationalism—the notion that nothing is quite real unless it’s endorsed by reasoned argument, and underwritten by more or less scientific proofs. But the human soul longs for enchantment. Those who don’t find their instinctive sense of the numinous satisfied by art, literature or music—let alone the discoveries of science itself—may well turn to the paranormal to gratify an intuition that mystery dwells at the heart of existence. Such people are perfectly placed to accept hoaxed evidence of unexplained powers and entities as real.

And so, the annual appearance of ever more complex patterns in the wheat fields of southern England is taken by “croppies”—the devotees who look beyond any prosaic solution for deeper explanations—as signs and wonders and prophecies. The croppies do, however, accept that some people, some of the time, are making some of the formations. They regard these human circle-makers as a nuisance, contaminators of the “evidence,” and denounce them as “hoaxers.” The term is well chosen, for it implies social deviance. And therein lies the twist in the story.

In croppy culture, common parlance is turned on its head. The word “genuine” usually implies that something has a single, identifiable origin, of established provenance. To the croppy it means the opposite: a “genuine” circle is of unknown provenance, or not man-made—a mystery, in other words. It follows that the man-made circle is a “hoax.”

Those circle-makers who are prepared to comment on this semantic reversal do so with some amusement. As far as they’re concerned, they are creating art in the fields. In keeping with New Age thought, it is by dissociating with scientific tradition that the circle-makers return art to a more unified function, where images and objects are imbued with special powers.

This art is intended to be a provocative, collective and ritual enterprise. And as such, it is often inherently ambiguous and open to interpretation. To the circle-maker, the greater the range of interpretations inspired in the audience the better. Both makers and interpreters have an interest in the circles being perceived as magical, and this entails their tacit agreement to avoid questions of authorship. This is essentially why croppies regard “man-made” circles as a distraction, a “contamination.”

Paradoxically, and unlike almost all other modern forms of art, a crop circle’s potential to enchant is animated and energized by the anonymity of its author(s). Doug Bower now tells friends that he wishes he had kept quiet and continued his nocturnal jaunts in secret. Both circle-makers and croppies are really engaged in a kind of game, whose whole purpose is to keep the game going, to prolong the mystery. After all, who would travel thousands of miles and trek through a muddy field to see flattened wheat if it were not imbued with otherworldly mystique?

As things stand, the relationship between the circle-makers and those who interpret their work has become a curious symbiosis of art and artifice, deception and belief. All of which raises the question: Who’s hoaxing whom?