The Courageous Photography of Lynsey Addario

The award-winning photojournalist has spent her adult life capturing the world in crisis, but now she chronicles her own life story

Read about the life of award-winning photojournalist Lynsey Addario and you’ll realize that she slows down about as often as her camera shutter does, which is to say not that frequently. In her new memoir, “It’s What I Do: A Photographer’s Life of Love and War,” the acclaimed photojournalist tells about photographing the American front line in Afghanistan’s Korangal Valley, where she scaled the Taliban-controlled hills alongside Marines of Battle Company and journalist Elizabeth Rubin. She writes about the story of her kidnapping in Libya and recounts the time her captors kindly bought her a new sweatsuit to wear, with the words “The Magic Girl!” emblazoned on the front. Addario’s memoir follows her life from childhood to her first assignments, through the height of her career, and ends with the birth of her first child. And throughout these momentous milestones, she hardly ever puts away her beloved cameras.

As a female photographer in male-dominated field, operating in a region of the world where women have few rights, Addario’s story takes on its own unique twists of plot and perspective. And in addition to detailing her ever-changing career assignments, “It’s What I Do” describes times of love, hurt, self-doubt, and the dedication it takes to overcome it all.

I spoke with Lynsey about her writing process.

What inspired you to write a book?

After I was released from Libya, I was approached by several different literary agents, asking if I was interested in writing a book. And frankly, I was not very interested at that point. I was actually more interested in doing a photo book, which I had never done. I was meeting with Aperture, and in the middle of our meeting I got a message that Tim Hetherington and Chris Honduras had been killed.

At that point, I stepped away from photography, and it felt more natural to write.

Is there anyone in particular you hope will read the book?

I hope young women will read it. I hope it will inspire them to follow whatever they feel is the path that they want to take in life and I hope it will inspire them to do what they feel passionate about, without feeling hindered. I was lucky because I had parents who have enabled me to do whatever I was passionate about, and never held my siblings and me back from anything. But I think a lot of people don’t have that experience.

Of all the places you’ve lived or worked, is there one place you call home? Or are there many places that you call home?

I grew up in Connecticut, going in and out of New York City, and I worked in the city in the ’90s. I was freelancing for the Associated Press, and I fell in love with New York.

I don’t feel like any of the places I work are home. There are places I feel at home, and there are places that I feel very comfortable because I’ve been going there so many years - Afghanistan, for one, where I’ve now been going for 15 years. I feel familiarity with places, but I think it’s important to not confuse them with going home.

Moving on to your photography, how often do you encounter expectations put on you in your work because of your gender?

Very often. But I actually welcome them! I think that more often than not, people underestimate me. People think, “She’s a woman, so she’s not going to be able to keep up,” or, “She’s a woman, so she’s not going to do anything sneaky.” If I’m working under a dictatorship, or if I’m trying to sneak into a country, I actually find it’s quite useful to be underestimated.

What are the advantages of that?

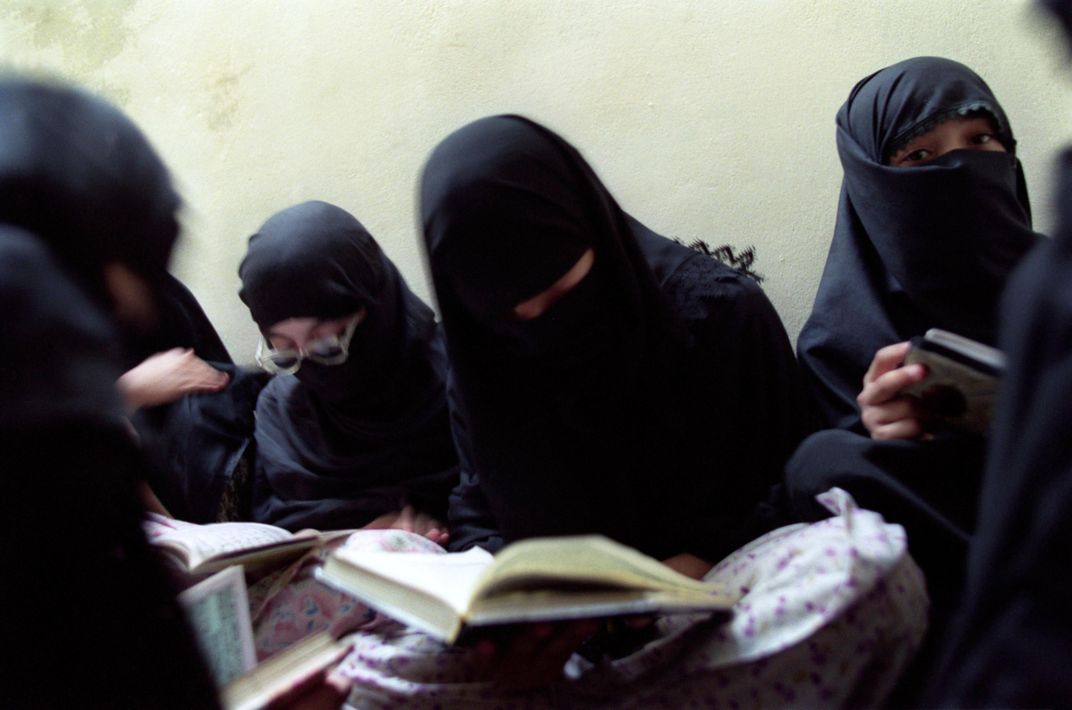

I don’t think I could have photographed the “veiled rebellion” story on women in Afghanistan for National Geographic in 2009-2010 if I weren’t a woman. Afghanistan is a deeply conservative country, where men and women rarely mix. It would have been impossible for a man to get access to women at home or to women in intimate settings. I was able to visit with midwives, with women in prison, and women who had attempted suicide by setting themselves on fire, and survived.

Has your gender ever felt like a disadvantage?

I always felt like it took a bit longer for me to gain the trust of the troops in remote bases who patrolled more dangerous areas. I had to prove my ability to keep up with rigorous patrols and hold my own during gun battles before they started looking at me as a photojournalist, and not as a woman.

I am looking at the photograph of the troops sitting by the tree stump. What was going on in that moment?

In the fall of 2007, I spent roughly two months on-and-off embedded with the 173rd Airborne, Battle Company, in the Korangal Valley of Afghanistan. The end of the embed culminated in a battalion-wide operation in the valley. The mission was to enter hostile areas, and look for Taliban and weapons caches. Blackhawk helicopters dropped us onto the side of a mountain, and we spent six days walking though the mountains with all of our gear on our backs. On the sixth day, our unit and scout team was ambushed by the Taliban from multiple sides, three soldiers were shot, and one of them died – Sgt. Rougle. I shot this picture minutes after troops had loaded Rougle’s body onto the helicopter. Their expressions of pain, grief, and defeat symbolized so much to me.

It seems that reporting on conflict has become more dangerous, that terrorists are targeting journalists. Some news agencies even refuse to accept work from freelance photographers in Syria. Have you experienced this shift yourself?

Today, I won’t go into a warzone without an assignment, and thus the backing from a reputable publication like the New York Times, who will have my back if something happens to me. I started my career covering conflict by saving money and sending myself to Afghanistan, but the nature of wars has changed dramatically. Journalists are targeted in a way that they were not targeted when I began 15 years ago. If publications want to publish images and stories from a certain person, they should put that person on assignment, cover his or her expenses, make sure they have access to security briefings and experts, someone to administer first aid, etc. The wire services like Reuters, AP and AFP have traditionally been on the frontlines of picking up local stringers and ensuring that they have proper training and support, but this has become more difficult as places like Syria become increasingly dangerous, and harder for journalists and westerners to acce