Clyfford Still’s Sublime Art

A new museum devoted exclusively to the work of the abstract painter is opening in Denver. A leading critic takes a close look at one masterwork

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Clyfford-Still-1954-PH1123-631.jpg)

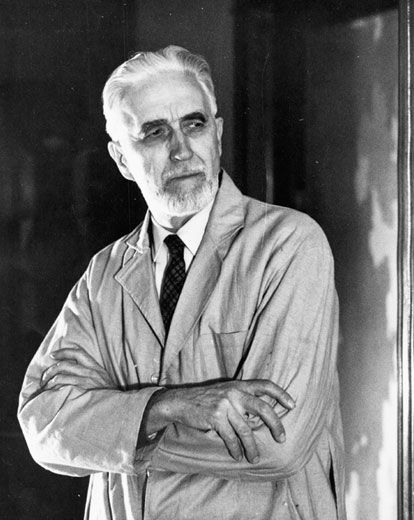

The American painter Clyfford Still (1904-1980) thought he was un-categorizeable, but many experts consider him to be, along with Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman, one of the few who painted the “abstract sublime.” The art critic and historian Irving Sandler says, “Jackson Pollock may have been the more important artist, but Still was, in my opinion, the greater innovator.” Still’s reputation is about to get a boost from the $29 million Clyfford Still Museum, designed by the star architect Brad Cloepfil and due to open November 18 in Denver. Its collection comprises more than 800 paintings and some 1,600 works on paper.

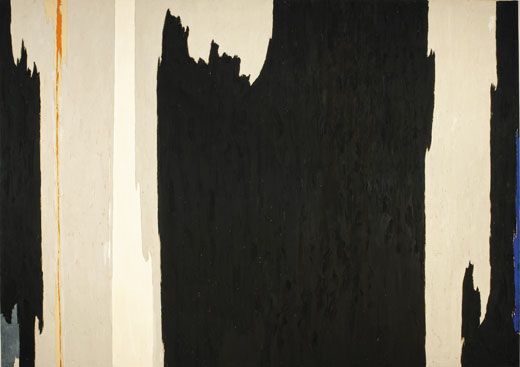

Still, who was born in North Dakota, took color by the throat, but his chroma is not French or perfumey, like that associated with Monet or Matisse. It’s stark, harsh, often accompanied by vast areas of black, but not unpleasant. In the roughly 9- by 13-foot canvas titled 1954 – PH 1123, Still’s handling of shape and paint itself is what makes the bright colors—the waterfall of orange, the semi-hidden tear of blue—register not only as beautiful, but as awesome in the literal, looking-out-at-the-Grand-Canyon sense of the word. The painting can be read from left to right, in a sequence similar to a three-act play. There’s an introduction, with that orange “character” getting your attention; a white-on-gray transition to the black, meat-of-the-matter second act; then a white climax followed by a black denouement.

But Still’s paintings aren’t narratives: They’re supposed to hit the viewer all at once. 1954 – PH 1123 does that, thanks to his control of vertical shapes, with undulating paint within a given color. He used varying amounts of linseed oil to achieve differences in gloss, and worked with a palette knife as much as a brush, lavishing attention on his cascading ragged edges. The effect is a stunning first notice, a rhythmic horizontal read and then a deep plunge into the painting’s inner structure.

My guess is that to stand in a gallery at the Clyfford Still Museum surrounded by the likes of 1954 – PH 1123 will be among the best art-museum experiences anywhere.

Peter Plagens is a painter and critic in New York City.