Broadway, Inc.

With shows like Legally Blonde and Wicked, the era of the name-brand musical is in full swing

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/broadway_lopez.jpg)

Debuting a show on Broadway, like attending the first day of a very expensive kindergarten, is an experience filled with fear, trepidation and even tears. If you stay long enough, however, you're uplifted by the storytelling and the songs, and you can't wait to do it all again tomorrow. Of course there's the small matter of tuition. Today, it can cost as much as $13 million to develop a Broadway musical through to opening night, and the immense pressure to make good on that investment has ushered in the era of the name-brand musical, the one that begins with something familiar—a book, a film, a Swedish pop sensation—and ends with audience members standing dazed in the lobby gift shop, debating whether to buy the T-shirt or the coffee mug.

By hedging their ideas with proven entities (see: The Lion King, Wicked, Mary Poppins, Legally Blonde), Broadway producers hope to add a dash of certainty to the mix of skill, luck, novelty, nostalgia and jazz hands required to succeed on the Great White Way. "There are no rules on Broadway," the author and screenwriter William Goldman once noted. "And one of them is this: art must be both fresh and inevitable; you must surprise an audience in an expected way." That could explain why the most commercially successful show for the past three Broadway seasons has been Wicked, based on the Gregory Maguire book that sheds light on characters from the classic American movie, The Wizard of Oz. Critics hated it. Audiences remain entranced. The show has grossed over half a billion dollars worldwide.

Although the trajectory of film to musical (and sometimes back to film, as with Hairspray) is increasingly popular, adaptation is not as new as it might seem. "There are all these movies being adapted into musicals now, and people tend to forget that after My Fair Lady (1956), until almost as late as 1973-74, there were many more things adapted from previous sources than there are now," says Broadway historian Laurence Maslon of New York University. "Everything from books like Don Quixote and Billy Budd to movies like The Apartment or Some Like It Hot. That was actually a much more fertile field of adaptation of known quantities."

The difference now? Branding. "There was a time when the Broadway musical felt that it needed to advertise itself as a new product," says theater critic Peter Filichia. And so Russell Bissell's novel Seven and a Half Cents became The Pajama Game, The Year the Yankees Lost the Pennant by Douglass Wallop got a new life as Damn Yankees and the 1939 Garbo film Ninotchka took the stage as Silk Stockings. "In those days, the '50s and the '60s, it was very important to put your best foot forward and say you're not seeing the same old thing you saw in the movies," says Filichia. "That's changed. Now the brand name of the property is important, and they want to make sure that people know that they're seeing a musical version

Broadway's emerging corporate mentality, seemingly so American, was actually spearheaded by a Brit, Cameron Mackintosh, the producer behind such megahits as Phantom of the Opera, Les Miserables, and the new musical Mary Poppins (a co-production with Disney). "He made the show the product, not the star, which is a complete 180 from the way Broadway had existed for decades," says Maslon. No longer did one go to see Ethel Merman as Mama Rose in Gypsy or Anna Maria Alberghetti headlining in Carnival; now people lined up to see an ensemble cast prowling the stage. In 1981, Mackintosh and Andrew Lloyd Webber co-produced Cats—the first name-brand musical aimed at the entire family, based on the 1939 poetry collection Old Possum's Book of Practical Cats by T.S. Eliot.

The focus gradually shifted from star performers to grand spectacles that could be reproduced on stages worldwide with multiple, modular casts. "Financially, producers said, 'Hey, that's working. And it's a lot easier to deal with than a performer,' " says Tony-award winning actress Tonya Pinkins. "Now Broadway is matching the corporate economic world, so we see the Disney musicals, all the movie brands, anything that was something else before is an automatic hit, and it's kind of critic-proof, because people already know it, they're familiar with it."

Some of the most successful shows of recent seasons—The Producers, The Color Purple and Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, to name a few—have plucked familiar names, plots and characters from their original sources. "If people already have a good taste in their mouth, they have an expectation of something, and that's being delivered," says Pinkins. Now in the works are musical versions of Shrek, Gone with the Wind and Desperately Seeking Susan. Dirty Dancing: The Musical holds the record for advance sales—taking in more than $22 million before opening in fall 2006—in the history of the West End, London's answer to Broadway. The show makes its North American debut this November in Toronto. This fall will also see the Broadway premiere of Mel Brooks's new musical, an adaptation of the 1974 film Young Frankenstein.

"From an economic point of view, if you have a proven property, something that's a hit, there's always going to be a desire to capitalize on that rather than risk it with an untested story," says Adam Green, who writes about theater for Vogue magazine. "I think that by and large, that's what's going to happen, but there's always going to be things that are original, like Avenue Q."

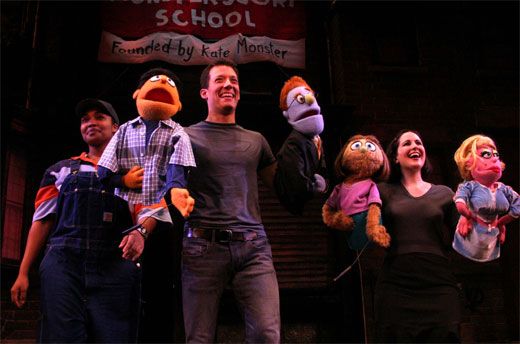

Still, Broadway's most original productions are influenced by existing works. "Writing a Broadway musical is so difficult that you need something to start from, a germ of an idea that may already exist or may already work," says Bobby Lopez, who co-wrote and composed the Tony-award winning musical Avenue Q, a show that features Sesame Street-style puppets in adult situations. "For us, it was the idea of children's television, and then we spun our own story and put a lot of ourselves into it."

Adaptation also tends to demand rigorous reevaluation of the original. "When you're writing an adaptation, you're absolutely writing it about yourself, pouring out your heart, and making it your own," says Lopez, who recently co-wrote Finding Nemo: The Musical, which is now playing at Disneyworld. "In order to remake something as a musical you need to completely rethink it. You have to reconsider the point of telling the story and why you care about it."

For Dori Berinstein, one of the producers of the musical version of Legally Blonde, it comes down to finding the best possible story and then figuring out how to tell it. "Both Legally Blonde the musical and Legally Blonde the film celebrate this amazing heroine who goes on a mission of discovery," says Berinstein, who captured contemporary Broadway in a 2007 documentary, ShowBusiness: The Road to Broadway. "Figuring out how to tell the story on a stage, live and in front of an audience, is a completely different thing. It's extraordinarily challenging, and it's not any different, really, than creating an original story."

New York City-based writer Stephanie Murg contributes to ARTnews and ARTiculations, Smithsonian.com's art blog.