To Bear Witness to Japanese Internment, One Artist Self-Deported Himself to the WWII Camps

The inhumanity brought on by Executive Order 9066 spurred Isamu Noguchi to action

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/43/f1/43f1a0ea-755c-4046-a6d0-924e637a8666/4_yellow-landscape-1943-hydrocale-wood-elements-string-and-wood-ball-photo-by-kevin-noble-wr.jpg)

For many, Isamu Noguchi is the guy who invented the classic mid-century coffee table— the one with the heavy glass and elegantly curved wood base that’s part of the Museum of Modern Art’s permanent collection and coveted by design addicts around world. Noguchi is indeed a design icon and is also considered one of the most influential artists in the United States. What’s lesser known is that during World War II, Noguchi voluntarily interned himself to try to improve conditions for his fellow Japanese-Americans, despite being personally exempt because he lived on the East Coast.

This February marks 75 years since President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, forcing those of Japanese ethnicity on the West Coast to inland relocation centers for the duration of the war. Two-thirds of people sent to these camps were American citizens. They were given only a few days to settle affairs— close their businesses, sell their homes— and gather the personal items they could carry.

Signed nearly two months after Pearl Harbor, Executive Order 9066 is a painful blight on America’s democracy, the epitome of a dark period of xenophobia and racism. Deemed a threat to national security, nearly 110,000 Japanese-Americans — including infants and children— were evacuated from their homes, confined by barbed wire and guarded at gun point in one of ten internment camps, across seven states.

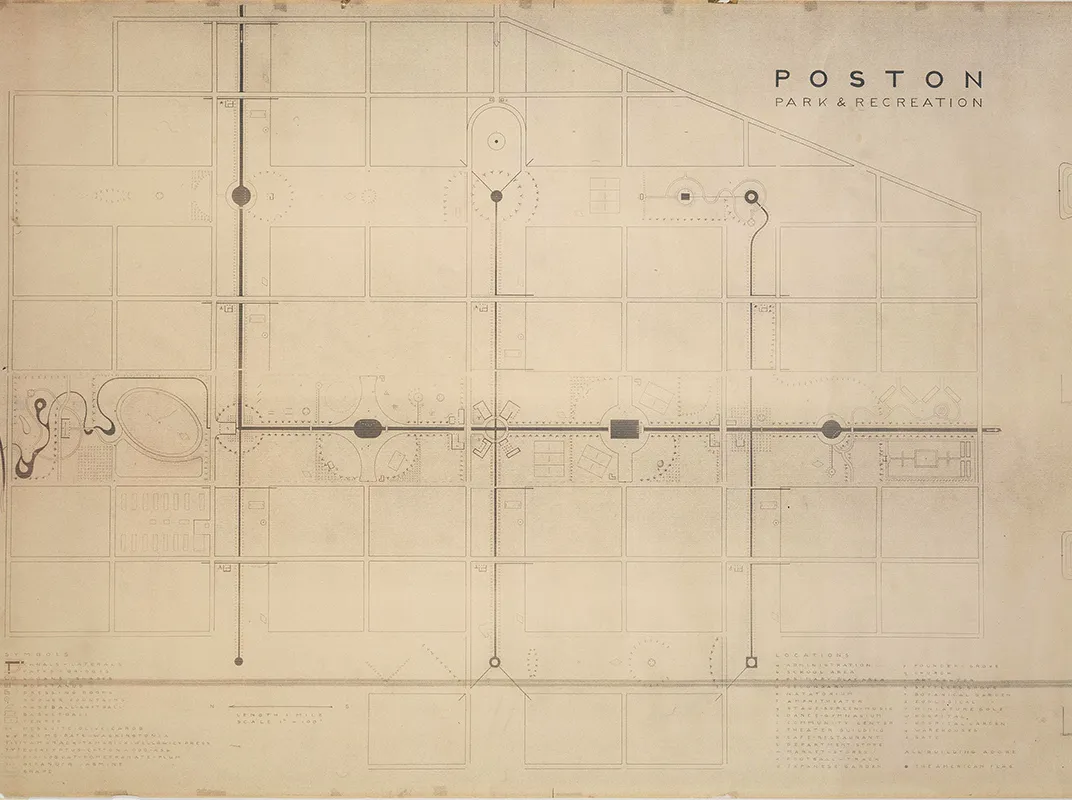

Later that year, Noguchi, at the time an established artist who had already built the iconic News sculpture on the façade of 50 Rockefeller Center, then “the Associated Press building,” met with John Collier, the head of the National Office of Indian Affairs, and ended up admitting himself to the Poston War Relocation Center in southwestern Arizona. (With over 18,000 inhabitants, Poston was situated on a Colorado Tribe Indian reservation under Collier’s jurisdiction.) Noguchi was hoping to contribute meaningfully to the plight of Japanese-Americans through the social power of art and design— in his own words, to “willfully become part of humanity uprooted.” He proposed teaching traditional Japanese craft, and suggested designs for several parks, gardens and cemeteries in the camps. After all, nobody knew how long the war or the camps would last.

At first, writes biographer Hayden Herrara in Listening To Stone: The Art and Life of Isamu Noguchi, the artist was “enthralled with Poston’s vast barren landscape” and “became a leader of forays into the desert to find ironwood roots for sculpting.”

But as the weeks went on, the broader social purpose of his internment did not go as planned. Art materials for his ceramics, clay and wood working classes never arrived; he wasn’t able to execute any of the public spaces he designed. And when Noguchi applied to leave (since he had volunteered to enter), camp officials initially denied his request due to “suspicious activities.”

This week, to coincide with the anniversary of EO 9066, the museum devoted to Noguchi’s career is opening Self-Interned, exploring the artist’s complex decision to enter Poston, where he lived from May to November of 1942.

“We don’t want to give the impression that Noguchi’s story is representative of the Japanese-American experience during internment,” says Dakin Hart, a senior curator at the Noguchi Museum. After all, he chose his internment. According to Herrera’s biography, the other prisoners didn’t feel they had much in common with him, a famous Manhattan artist. “But his experience is prismatic,” Hart adds. “And of course, things changed for Noguchi once he was there and he couldn’t easily leave.”

“Noguchi was an intense patriot,” Hart says. “But a patriot of humanity first, of the planet and the global community.” In many ways, his personal story is one of profoundly typical “Americanness” that crisscrosses cultures and the country’s physical landscape. Born in Los Angeles to a Brooklynite mother and a father who was an itinerant, Japanese poet, Noguchi attended middle and high school in La Porte, Indiana, and is, in Hart’s description, “a true Hoosier,” in the old-fashioned sense of being “self-reliant and inclined toward efficiencies.” At that time, he went by the “Americanized” name “Sam” Gilmour (after his mother’s family). Biographies describe Noguchi’s middle-class teen years as fairly typical, complete with the requisite all-American, paper route. In these ways, World War II, Hart explains, was emotionally shattering because it pitted the two halves of his identity against each other as they committed the most “inhumane conceivable things to one another”

In addition to sculptural work, Self-Interned presents documents from mailing lists and activist groups that Noguchi collected, explains Hart. “From these written materials, what you realize is the fundamental presumption [by government authorities] that someone of Japanese heritage was not part of the American community,” he says. It was this built-in assumption of guilt or “pernicious otherness” that struck Noguchi from 3,000 miles away in New York. (The Smithsonian American Art Museum is currently exhibiting a retrospective of Noguchi's career.)

Noguchi is certainly the most famous Japanese-American to create art under these bleak conditions. But there is a wider body of work salvaged from internment camps— a testament to the power of art’s transcendence and dignity in times of extreme hardships. For example, a 2011 Smithsonian America Art Museum exhibition at the Renwick gallery, guest-curated by Delphine Hirasuna and based on her book, The Art of Gaman, displayed more than 120 objects—teapots, furniture, toys, pendants and musical instruments— made by Japanese-Americans, from 1942 to 1946, out of scraps and materials they found in captivity. And in 2015, The Art of Gaman traveled to Houston’s Holocaust Museum. Remarkably, Jews under some of history’s most inhumane conditions were still secretly painting and drawing in the ghettos and in concentration camps. Last winter, the German Historical Museum exhibited 100 pieces of art created by Jews amidst the Holocaust from the collection of Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center in Jerusalem. Many of the mages evoke an alternative world, evidence of unimaginable strength and spirit in the face death and torture.

While at Poston, Noguchi was also helping to organize a retrospective of his work with the San Francisco Museum of Art (the predecessor of today’s SFMOMA). The exhibit opened in July 1942, with the artist still confined to an internment camp and San Francisco, as Hart explains, in the grips of “widespread racist paranoia that sanctioned such abominations as the sale of ‘Jap hunting’ licenses.” After Pearl Harbor, some of the museum debated whether to continue with the exhibit. Perhaps most moving, in a letter to the museum’s board of trustees, museum director Grace McCann Morley wrote, “The cultural and racial mixture which is personified by Noguchi is the natural antithesis of all the tenants of the axis of power.”

“The new arrivals keep coming in,” wrote Noguchi in an unpublished Poston essay. “Out of the teeming buses stumble men, women, children, the strong, the sick, the rich, the poor…They are fingerprinted, declare their loyalty, enlist in the war Relocation Work Corps…and are introduced to their new home, 20 x 25 feet of tar paper shack, in which they must live for the duration five to a room.”

In the 21st century, art is too often thought ancillary or supplementary—a by-product of society’s comfort and safety. And thus, art objects lose their rightful consequence. Paintings become pretty pictures; sculptures are merely decorative or ornamental. But Self-Interned reminds viewers that art is about survival. Artists always create, even when the rules of civil society are suspended and things fall apart around them (perhaps then, only more so). They do it to bear witness, as Holocaust archivists describe, and to give their communities hope and nobility with creativity and aesthetic beauty, no matter how much their government or neighbors have betrayed them. Decades later, sculptures like Noguchi’s from this period especially, show us humanity’s common threads, which history shows inevitably slip from our collective memory.

Ultimately, this is the power of Self-Interned. It is successful as both an ambitious art exhibition and a cautionary tale amidst modern-day discussions of a registry of Muslim immigrants. There may always be hatred and fear of ‘the other,’ but there will also be artists who manage to create things of beauty— to elevate us from our surroundings and remind us of our sameness— when we need it most.