Baghdad Beyond the Headlines

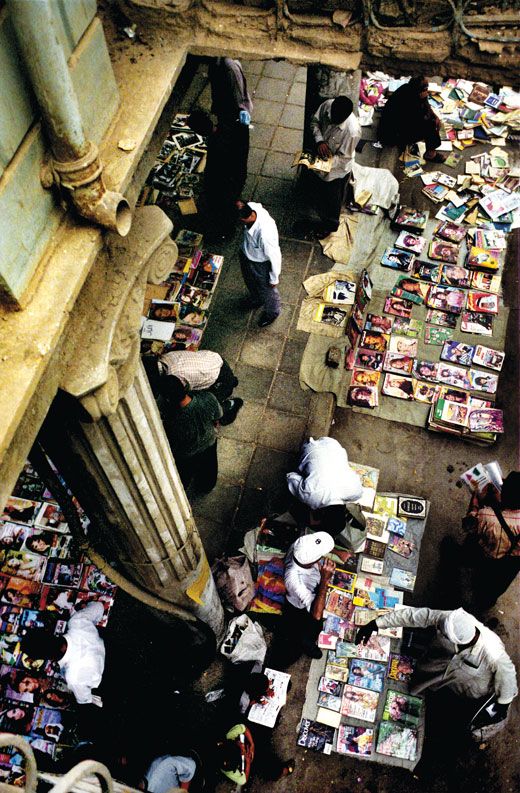

From gleeful schoolkids to a literary scholar who loves Humphrey Bogart, a photographer captures a reawakening but still wary city

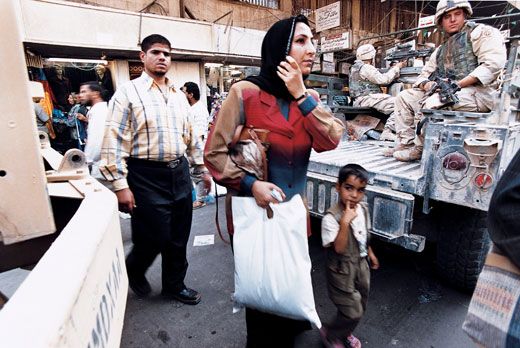

Photojournalist Lois Raimondo had little idea what to expect. Her impressions had come mainly from daily news reports of the fighting and casualties and the coalition government's struggles to gain a footing on unstable ground. Journalists in the city warned her to be off the streets by dark.

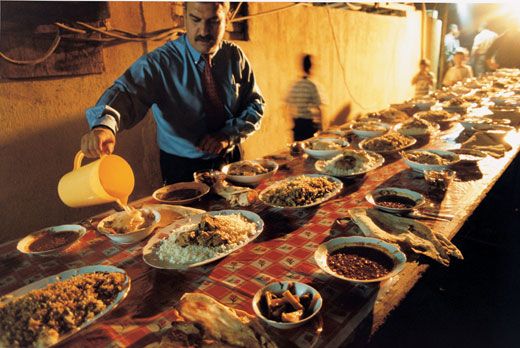

A few hours after arriving in Baghdad, she found herself at a run-down estate in a Baghdad suburb. The sun had set, marinated carp was roasting on the fire, and whiskey and Iraqi beer were flowing. The ebullient host, Sala, an Iraqi businessman newly returned after 15 years in London, urged everyone to eat and drink. They talked above the crack of distant rifle and machine-gun fire. But when mortars began to boom, guests began to leave. "Please stay," Sala said, laughing and crying at the same time. "It's a party."

His strong mixed emotions made a fitting introduction to Baghdad. Raimondo had gone there to see how people were getting by in their daily lives. Do they have enough to eat? What are they doing for work? What are their dreams for the future?

In a neighborhood of stucco houses, the headmistress of a primary school told Raimondo that she was angry about the destruction of Saddam's regime. She described him as a father figure to her as well as her students. "People love Saddam because they are afraid of him," the journalist's driver, a 42-year-old man named Ali, explained. "This is a very strong kind of love. We are always afraid to say our feelings."

Raimondo visited a married couple in their 40s, both unemployed meteorologists. The mother worried constantly about their two young children because of the bombings and shootings. The father had been a Baathist and a general in Saddam's air force. He'd been hiding in the house since the start of the war. "Everything outside is chaotic," he said. As Raimondo left he said, "This was not so difficult. You are the first American we have ever met."

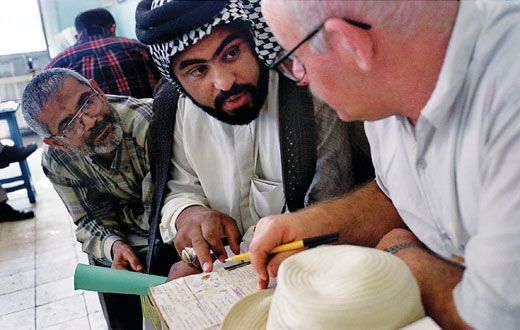

Raimondo noticed how people were speaking up after decades of suppression. "From now on, there will be a big difference," a furniture maker said. "At the very least I can talk."