Artisanal Wheat On the Rise

Giving factory flour the heave-ho, small farmers from New England to the Northwest are growing long-forgotten varieties of wheat

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Wheat-Tevis-Robertson-Goldberg-631.jpg)

Under the warm August sun, the wiry, lushly bearded farmer moves at a slow walk through the field, swinging his scythe in a steady rhythm, the tawny stalks of wheat falling to one side in neat rows. From time to time he pauses to hone his curved steel blade on the stone he keeps in a belt pouch. He is followed by three or four young women, who gather the felled stalks by the armload, picking out the stems of mayweed and ragweed, tying the wheat into sheaves, and standing up the sheaves into shocks that will dry and ripen in the sun until they in turn are assembled into circular head-high ricks that will resist the autumn rains until the time to bring the harvest indoors for threshing.

Civilization began like this, as acknowledged in Genesis with the Lord’s decree that “in the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread,” and thus it was until the invention of the mechanical harvester and the combine. Then a vast monoculture of wheat spread across much of the land, abetted by railroads and chain supermarkets, bequeathing unto the nation bread untouched by human hands from the moment the seed goes into the ground until the loaf is unwrapped and the slice anointed with peanut butter. That the scythe-wielding farmer is seeking to reverse 150 years of industrial history is an act of, at the very least, hubris. That he is attempting to do it in the foothills of the Berkshire Mountains on an acre of heavy, cold soil containing a limitless supply of stones to menace his blade seems to border on madness.

But there’s something about wheat. It speaks to the American soul like no other crop, even much more valuable ones, which is most of them. Find a penny from before 1959, and what you see on the reverse are two iconic stems of wheat, not a bunch of arugula. “Man does not live by salad alone,” says the Berkshire farmer, Tevis Robertson-Goldberg of Chesterfield, Massachusetts. “He needs croutons, too.” In growing grain where it has not been grown in living memory, Robertson-Goldberg is pushing the boundaries of locavorism, the national movement that obsessively tracks the miles covered in every calorie’s journey from earth to mouth, combining elements of environmentalism, survivalism, nutritional fanaticism, common sense and food snobbery.

As recently as 2005, when the writers Alisa Smith and J.B. MacKinnon tried to live for a year exclusively on food grown near their home in Vancouver, flour was among the most elusive staples; in their book, Plenty, they describe the tedium of separating mouse droppings from the grain in the only sack of wheat they could find within 100 miles. They would not have that problem today; farmers in the lush Skagit Valley north of Seattle, whose leading products are potatoes, tulips and vegetable seed, have begun adding wheat to their crop rotations for what one of them, Dave Hedlin, calls “fun, and occasional profit.”

Like many farmers, Robertson-Goldberg planted wheat as a cover crop, something to keep down the weeds on a field being rested from the more demanding work of growing the broccoli, berries, rutabaga and other vegetables he supplies to farmers markets and to families who pay a flat sum for a share of his production, an arrangement called community-supported agriculture (CSA). But standing tall in the late-summer sun, the wheat looked so beautiful he couldn’t bear to plow it under.

His only real qualification to raise wheat was knowing how to scythe, a skill he’d picked up during a year at a “living history” farm in New Jersey. (Scything, he says, “is harder and less dangerous than it looks.” The other way to harvest wheat, if you don’t happen to own a combine, is with a sickle, a curved blade attached to a short handle, and wielding one of those is easier and more dangerous than it looks.) He didn’t even have wheat seed, at least not of the heirloom varieties he was interested in growing. One of those varieties is Arcadian, which was grown in New York State as recently as the 1920s; it had gone so thoroughly out of fashion that when officials from the U.S. Department of Agriculture sought it for their seed bank in 1991, they had to get it from Russia. (And even that, he says, may not be identical to the New York strain.) The seed bank provides only five grams to a customer, or about 100 seeds. These, after one growing season, yielded Robertson-Goldberg a pound of seed, which turned into ten pounds the following year, at which point he was ready to have a crop. And he would have harvested one, too, if a hurricane hadn’t hit the Northeast this past fall.

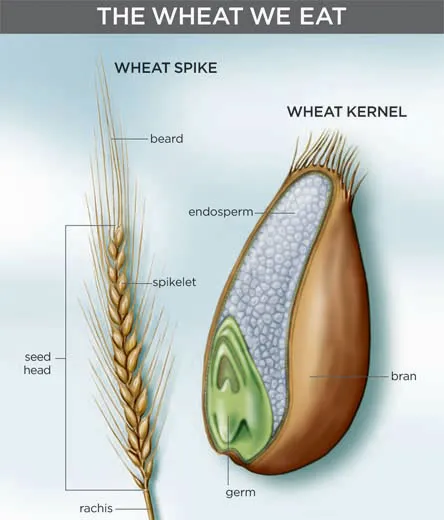

Even home gardeners are planting wheat, in backyards measured in square feet rather than in acres. They are harvesting it by hand, threshing it by flailing chains inside plastic buckets, separating the chaff from the berries (or kernels) with vacuum cleaners and then grinding it themselves on hand-cranked mills. This is an impulse entirely separate from the desire to grow, say, tomatoes, which are obviously better and cheaper from a garden than a supermarket. As an economic proposition, raising wheat to save money on flour makes about as much sense as raising children to help with the dishes. In either case, the decision is an emotional one. Home-grown wheat springs from the soil of American self-reliance and independence, fertilized with a pinch of apocalyptic fervor. Jack Jenkins, a genial tinkerer who sells hand-cranked tabletop mills by mail order out of Stanwood, Washington, cites a customer who connected two of his machines in tandem to a stationary bicycle and in a year “processed enough flour to bake 1,456 loaves of bread. She trained for a marathon that way!” Jenkins praises the taste and nutritional value of freshly ground whole-wheat flour, but also notes, pointedly, that unmilled wheat can potentially keep for decades, a useful quality if you’re stocking up in advance of social and economic collapse. (Flour has a definite shelf life, which can be extended by refrigeration, Jenkins notes—“if you’re sure you’re going to have electricity.”)

The unlikely ground zero for the nouveau-wheat movement is Skowhegan, Maine, in a region that was, long ago, one of the breadbaskets of America. It was here in 2007 that the annual Kneading Conference was born, a celebration of bread bringing together small farmers, artisanal bakers and practitioners of the obscure art of building outdoor wood-fired brick ovens. The missing link in re-establishing the area’s self-sufficiency in bread was a mill, so two of the conference organizers, Amber Lambke and Michael Scholz, constructed one in a vacant building that had been the city’s jail. This year, the Kneading Conference spun off a West Coast satellite event, held in September at the Washington State University (WSU) research center in Mount Vernon and organized by its director, a WSU plant geneticist and plant breeder named Stephen Jones. “Farmers here need wheat in their rotation, but they lose money growing it,” Jones told an appreciative crowd at the conference. “They just want to lose a little less money.”

Tom Hunton, a farmer in the Willamette Valley of western Oregon, where a leading crop is grass seed, said he became restless growing “things you can’t eat.” He was encouraged in this change of heart by the housing collapse, in which the market for lawn seed was collateral damage. He planted a field with hard red wheat, the kind used for bread flour. The infrastructure of the valley was geared to transporting soft white wheat—used for pastry and noodles—to ports for shipping to Asia. Hunton at first had his wheat custom-milled, but then he too built his own mill, the Camas Country Mill, in Eugene. When it opened, this past spring, it was the first in the region in 80 years.

In semi-rural Dutchess County, New York, Don Lewis, a farmer and baker, built an artisanal “micromill” to process locally grown grain for sale at his own farm store and bakery and to supply the voracious epicures of New York City, some 100 miles away. “The nation owes its very existence to Hudson Valley wheat,” Lewis avers, because the grain allowed the Continental Army to eat fresh bread, while British troops were gnawing stale hardtack. (Legend has it that Catherine Schuyler, the wife of the American Gen. Philip Schuyler, burned her wheat fields near Albany to keep them from the British—the subject of a painting by Emanuel Leutze, who also painted Washington Crossing the Delaware.) The heyday of Hudson Valley wheat ended in the 19th century with the spread of a stem-devouring pest called the Hessian fly, which supposedly had been brought by Britain’s Hessian mercenaries, and the opening of efficient transport routes from the Midwest. But the land and the climate are still there, and people are still eating bread.

One of the effects of this movement is to change the very nature of wheat, as obscure antique varietals are slowly going from seed banks into the ground, and thence the oven. As a commodity, bought and sold on exchanges in Kansas City, Chicago or Minneapolis, wheat is defined by three dichotomous characteristics—that is, whether it is hard or soft, red or white and winter or spring. Hard wheats, high in protein, give bread its body; soft wheats are preferred for pastry and noodles. Red wheat has a little more edge to its flavor than white, and winter versus spring has to do with when the wheat is planted and harvested. But wherever it’s grown, on city-size farms from Texas north to the Dakotas and west to Washington State, commodity wheat is a modern variety, bred for yield, disease resistance, ease of harvesting and, above all, consistency, right up to the moment it pops out of your toaster.

But that system, for all its efficiency, fails to exploit the fantastic genetic diversity of wheat. It is a plant that Abdullah Jaradat, a research agronomist with the Agriculture Department, describes as “perhaps the most variable crop on earth,” growing from the equatorial highlands up to the Alaska panhandle. The genome of most modern wheat is the largest ever decoded by biologists, including those of corn, rice and the creatures who plant and eat them. It comprises three distinct subgenomes, Jaradat explains, “each from a totally different plant, but together they act as one.” They joined in two events of natural hybridization, in the Fertile Crescent some 10,000 or 12,000 years ago, and on the southeastern coast of the Caspian Sea in what is now Iran some 3,000 or 4,000 years later.

It was this second event that gave wheat its enormous adaptability, a trait that Eli Rogosa, director of the Heritage Wheat Conservancy, thinks may prove to be the salvation of humanity as the climate changes and pests evolve. On her Massachusetts farm she cultivates an array of rare “landraces,” organic heritage breeds that are adapted to particular ecological niches, but with the genetic capacity to thrive in many different environments. Many of these bear exotic names seemingly out of the Arabian Nights—emmer and einkorn and Ethiopian Purple, Poltavka and Zyta and Rouge de Bordeaux—and were collected from gene banks and traditional farmers in Europe and the Middle East. Rogosa showed them off this past July at a conference on Bread, Beer and Biodiversity at the Amherst campus of the University of Massachusetts, from which Don Lewis returned with a half-dozen samples to grow on his Hudson Valley trial plots. “I’m in business,” he says with a shrug, “but I’m also trying to feed the valley, as much as possible, with what we grow here.” As Elizabeth Dyck of the Organic Growers’ Research and Information-sharing Network notes, “It has always been a deluded idea that you should cede the production of the foodstuff you eat the most to another part of the world.”

Of course, the part of the world that actually produces that foodstuff tends to disagree. “Heritage wheat?” says Jeff Borchardt, president and CEO of the Kansas City Board of Trade, through which contracts representing 800 million bushels of hard red winter wheat, the raw material of uncountable billions of sandwiches, pass each year. “I’ve heard of it, I guess. But I can’t say I’ve ever had any.” It was in Topeka, capital of the nation’s leading wheat-growing state, that a bakery last spring had to stop selling its popular cider doughnuts at a farmers market because it could not obtain enough Kansas-grown whole-wheat flour. “In other areas of the country, grain farmers and bakers have gotten together and they’re trying to rebuild that infrastructure that we’ve lost through consolidation,” Mercedes Taylor-Puckett of the Kansas Rural Center told the Lawrence Journal-World. “And so, it would be really interesting to explore whether we can look at grain in Kansas as a product, not just a commodity.”

For locally grown heritage varieties of stone-ground wheat to become more than a novelty, there must be a consensus that the flavor of the wheat is carried into the bread. Many people are willing to pay a little extra for their baguette if it helps support local agriculture, but many more would do so if they were convinced that it tasted better. Does wheat have varietal characteristics? Does it reflect “terroir”? Those are still controversial questions, and even bakers who think they can taste the difference between wheat varieties agree that it’s small. “I’ve had very good chefs tell me there’s no difference between 19-cent commodity flour and $1 specialty flours,” June Russell of the New York City Greenmarket told the UMass conference. “We’ve got to close that knowledge gap, to develop a vocabulary of taste for wheat, like we have for wine.” Even growers and bakers who have bought into the artisanal philosophy wonder how far to push it. “We’ve had to get used to using local grains,” says Jim Amaral of Borealis Breads, a large Maine bakery. “They vary. No one is blending them for consistency. Our breads are flour, water, salt and starter. If that’s all you’re using, the ingredients really matter.” On the other hand, he adds, “it emphasizes your connection to the land. The consumer has to understand that wheat is a seasonal product, like blueberries. But even then, there is a window of acceptable variability, and you cannot go outside it.”

In fact, the paradigm shift is already happening, and no one knows it better than Jones, the organizer of the Kneading Conference West. For a bread demonstration, he gave one of the bakers in attendance, George DePasquale of Seattle’s Essential Baking Company, a sample of flour from Bauermeister wheat. This is a variety Jones himself developed in 2005. Like most breeders at the time, he was interested in qualities such as yield, disease resistance and protein content. He was a little surprised, then, to hear DePasquale rave about the flavor of the resulting bread as “the best in 35 years of baking...nice controlled acid flavors [with a] strong hit of spice, strong hit of chocolate.” Jones, who has been involved in wheat-breeding since 1981, said, “That’s the first time I’ve ever heard it described that way.” But he also acknowledges that future breeders will increasingly consider that subjective and hard-to-measure quality of flavor.

Around the time of the conference, it was raining in Massachusetts, where Robertson-Goldberg’s wheat was still standing out in the fields, gathered into neat ricks and covered with tarps, awaiting time and space in the barn for threshing. It turned out that ricks, at least the ones he built, couldn’t stand up to Hurricane Irene. Some of the harvest got wet and sprouted. “I am still figuring out the art of building a sound, weather-proof rick,” he wrote in an e-mail after the rain stopped. “The best instructions I can find in old books is ‘get an old-timer who knows how to do it to show you.’ Which is not particularly helpful, as I don’t think there is anyone left alive with much experience.” Still, it was not a total loss, he cheerfully noted; although he won’t get enough good flour to do the baking trials he wanted to do, he managed to salvage enough seed to plant again for 2012.

Jerry Adler wrote about modernist cooking in the June issue of Smithsonian. Amy Toensing is based in New Paltz, New York; Brian Smale also photographed “Native Journey.”