An Unforgettable Photo of Martha Graham

Barbara Morgan’s portrait of the iconic dancer helped move modern dance to center stage

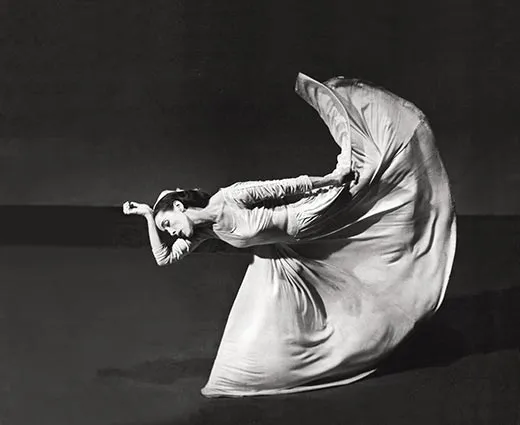

Barbara Morgan’s 1940 image of Martha Graham in the ballet Letter to the World may be the most famous photograph ever taken of an American dancer. It ranks, in honor, with Ansel Adams’ photographs of Yosemite and Walker Evans’ of small-town churches, and it bears much the same message: Americans’ belief in the flinty, frank truth of their vision of life, as opposed, say, to European decorativeness and indirection. That faith was especially strong around the mid-20th century, and in the minds of certain artists it was allied especially with the American Southwest: the hogans, the cliff-hemmed mesas, the vaulted skies. D.H. Lawrence and (the best-known example) Georgia O’Keeffe lived there. Many others traveled there, including the California photographer Barbara Morgan.

Born in 1900, Morgan worked in several media—printmaking, drawing, watercolor—but by the mid-’30s she was concentrating on photography, partly because it was easier to do with two children in the house. In the summers, she and her husband, Willard, a writer and photographer (he would be the first director of photography at New York City’s Museum of Modern Art), visited the Southwest and turned their cameras on the landscape. Another devotee of that part of the country was the dancer and choreographer Martha Graham. Graham, born in 1894, first visited the Southwest in 1930. The place hit her like a brick, and confirmed her quest for an austere and ritualistic style.

Thus when Graham and Morgan met, in 1935, they found they had a shared interest. Indeed, they had much in common. Both were dedicated modernists and hence, at that time in America, bohemians, iconoclasts. In addition, both were highly idealistic, given to pronouncements on the Spirit, the Essence and so forth. According to the philosopher Curtis Carter, a friend of Morgan’s who has curated three exhibitions of her work and written most of what we know about her, Morgan had first seen Graham’s work several years earlier. We don’t know if Graham had seen Morgan’s work, but apparently she sensed a kinship. Within a short time Morgan proposed to do a book of photographs of Graham, and the choreographer said, “Fine, let’s do it.”

It was not an easy project. “She was a terror,” Graham told an interviewer years later. “I’d do it, and then she’d say, ‘Well, the dress wasn’t quite right,’ and then we’d have to do it again. First she would make me lie down on the floor and rest. So off came the dress (it mustn’t get dirty, you know), and then we’d start all over again.” Morgan had her reasons—exalted ones, as usual: “I wanted to show that Martha had her own vision,” she said about the photo shoots. “That what she was conveying was deeper than ego, deeper than baloney. Dance has to go beyond theater....I was trying to connect her spirit with the viewer—to show pictures of spiritual energy.” Graham probably agreed. In the book Morgan finally produced in 1941, Martha Graham: Sixteen Dances in Photographs—which contained the Letter to the World image—Graham writes, “Every true dancer has a peculiar arrest of movement, an intensity which animates his whole being. It may be called Spirit, or Dramatic Intensity, or Imagination.”

Nowadays, these words sound a little high-flown, as do many writings of the period (think of Eugene O’Neill or Tennessee Williams), but the combined ardor of Graham and Morgan produced what—with maybe one competitor, George Platt Lynes’ images of George Balanchine’s early work—were the greatest dance photographs ever made in America. Morgan thought she was just celebrating Graham. In fact, she was celebrating dance, an art often condescended to. The composition of the photograph is beautiful—the horizontal line of the torso echoing that of the floor, the arc of the kick answering the bend of the arm to the forehead—but this is more than a composition. It is a story. Letter to the World is about Emily Dickinson, who spent her life shut up in her family’s house in Amherst and who nevertheless, on the evidence of her poetry, experienced in those confines every important emotion known to humankind. Graham’s dance was accompanied by readings from Dickinson, including:

Of Course—I prayed—

And did God Care?

He cared as much as on the Air

A bird—had stamped her foot—

And cried “Give me!”—

Unanswered prayers: most people know what that means. Hence the seismic power of the photograph.

Both Morgan and Graham lived to be very old, Morgan to 92, Graham to 96. Graham became this country’s most revered homegrown choreographer. She, more than anyone else, is now considered the creator of American modern dance. Twenty years after her death, her company is still performing. Morgan’s reputation remained more within the photographic and dance communities. By the late 1970s, her book was out of print (old copies were selling for $500) and it was often stolen from libraries. But it was reprinted in 1980.

Joan Acocella is the dance critic for the New Yorker.