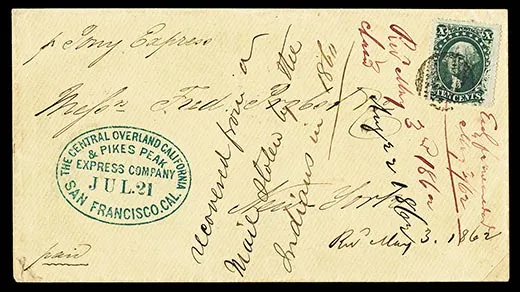

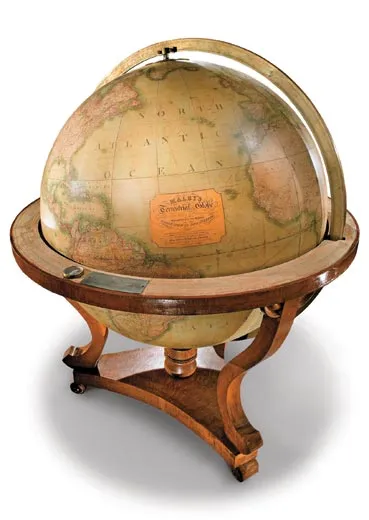

A Rare Pony Express Artifact

A letter that took two years to reach its destination evokes the hazards of the Pony Express

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ATM-Object-Pony-Express-letter-631.jpg)

In 1860, an ill-fated Pony Express rider, whose name has been lost to history, was crossing the trackless wastes of Nevada when he vanished, likely killed by Indians. Two years later, in May 1862, the mail pouch from that doomed mission, still containing letters bound for the East, was recovered.

Today, only a few remnants from the contents of that saddlebag survive. Among them is an envelope—a rare artifact of the mid-19th-century’s legendary Pony Express mail service, founded 150 years ago. (The letter that was inside has long since disappeared.) The philatelic treasure will reside on long-term loan at the Smithsonian’s National Postal Museum (NPM). Recently, the envelope’s owner, William H. Gross, a passionate stamp collector since childhood, donated funds for a new 12,000-square-foot gallery at the museum, scheduled to open in 2012. The envelope will take pride of place in the new exhibition space. “There are only two pieces of what collectors call ‘interrupted mail’ from the Pony Express known to exist, and they were in that rider’s pouch,” says NPM curator Daniel Piazza.

The concept of expedited mail delivery by a relay of single riders on fast horses—a kind of grass-fueled FedEx—echoed the vision that won the West. Established in April 1860, the Pony Express failed to win a major contract from the federal government and was replaced by a stagecoach line after only 18 months. Yet its bravado has colored the mail service ever since.

The transcontinental delivery system was marvelous in its simplicity. Across 1,900 miles, at 186 stations between St. Joseph, Missouri, and Sacramento, California, fresh horses awaited carriers who rode at full gallop in 10- to 12-mile segments (judged to be the maximum distance that a good mount could maintain a speedy clip). At each station, the rider leapt off one horse and onto the next, then sped on. The tough, wiry horsemen covered up to 125 miles at a stretch—a punishing pace that commanded a then-substantial salary of $25 per week. William “Buffalo Bill” Cody and James “Wild Bill” Hickok boasted they had earned their spurs as young Express riders. “Or so they claimed,” says Piazza. (There is no evidence that either did so.)

The rare 1860 envelope attests that hard riding was not the most daunting aspect of the job. Routes passed through deserted, often forbidding, territory. A note scrawled on the front of the artifact alludes to its tragic backstory: “Recovered from a [sic] mail stolen by the Indians in 1860.” The nameless victim is thought to have been the only Pony Express rider killed, though a few station agents died when Indians attacked their outposts.

The letter at last reached its destination—a New York City business recorded only as Fred Probst & Co.—in August 1862. Says Piazza: “So much happened between when the letter was sent and when it arrived—Lincoln’s election, the secession crisis, the beginning of the Civil War.” (In March 1861, the Pony Express set a record for transcontinental delivery—7 days 17 hours—when riders carried Abraham Lincoln’s Inaugural Address to the West Coast.) The envelope bears an oval stamp that reads “The Central Overland California & Pikes Peak Express Company,” the enterprise that administered the Pony Express. It had disbanded nine months before, on October 26, 1861.

The envelope also bears a basic 10-cent stamp, which normally would have meant a two-month trip, as the letter traveled from San Francisco by ship down the West Coast, across the isthmus of Panama and by sea up the East Coast to New York City. The additional cost for Pony Express service—guaranteed to reach the East Coast in about 12 days—was $5 (roughly $133 in today’s currency) per half-ounce.

Ultimately, says Piazza, even the envelope’s stamp, with its image of George Washington, offers a history lesson. “Although the letter was delivered,” he says, “the 10-cent stamp was no longer valid. At the beginning of the [Civil] War, all existing postal stamps were demonetized so the Confederacy couldn’t use them.”

Owen Edwards is a freelance writer and author of the book Elegant Solutions

Freeze Frame » Smithsonian Institute Archives

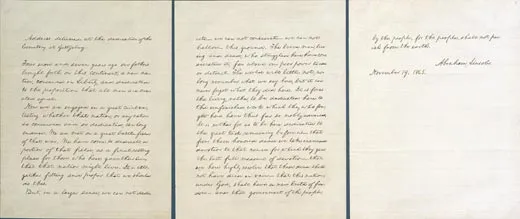

Inventive Abe » Alfred Harrell

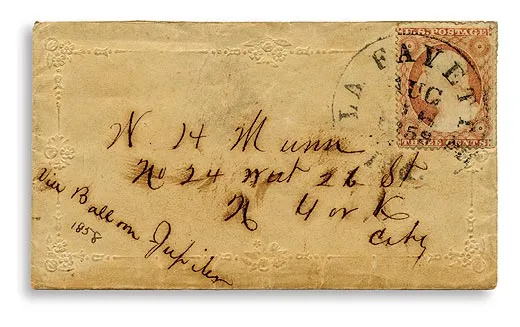

Airmail Letter » National Postal Museum

Dead End » Jeff Tinsley/National Museum of American History, S.I.

Refined Palette » Mary Hoffmeier/Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

American Idol » Hugh Talman/National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution

Christmas Cards » Mark Avino/National Air and Space Museum, S.I.

John Lennon's First Album » Bill Lommel/National Postal Museum, SI

Casualty of War » Lee Stalsworth/Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpt ure Garden. Smithsonian Institution

The Shirt Off His Back » Jeff Tinsley/National Museum of American History

Romance And The Stone » Chip Clark/National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution

Sky Writer » National Air and Space Museum, S.I.

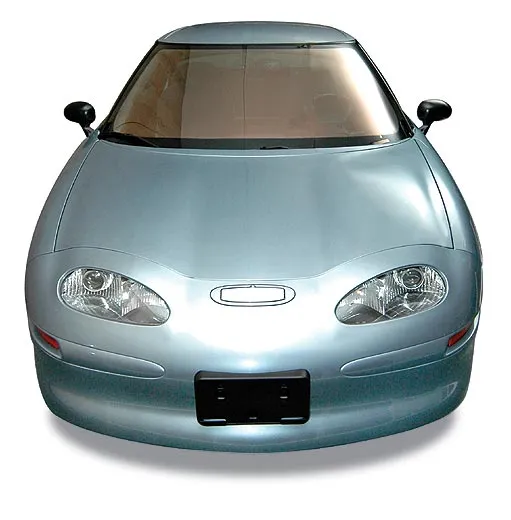

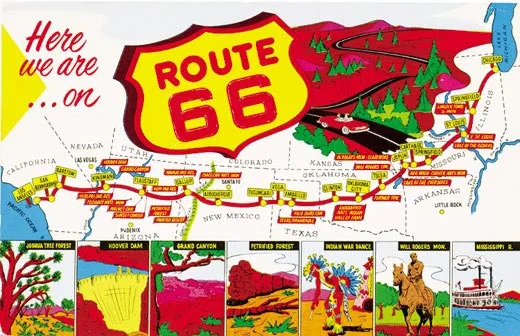

Antique Road Show » National Museum of American History, Transportation Collection, Smithsonian Institution

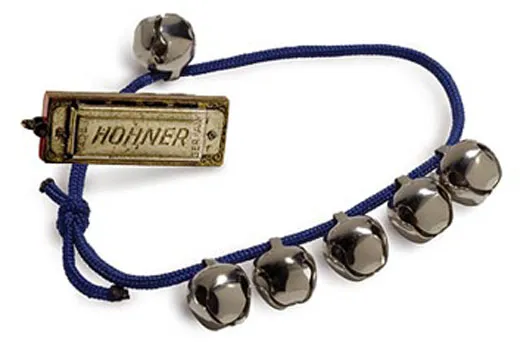

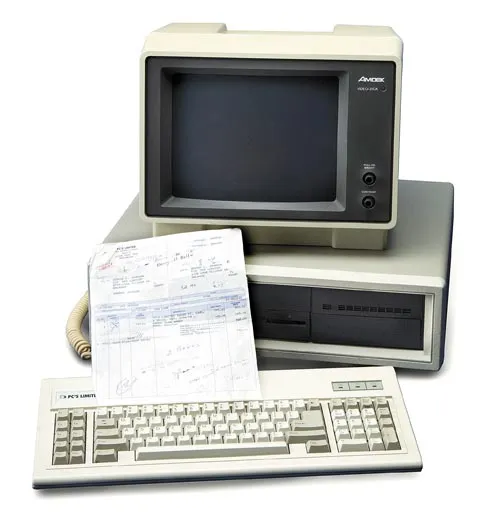

Useful Gadget » Kim Nielsen/Smithsonian Institution

National Museum of American History

Wild Thing » Jeff Tinsley

Here's Looking at You, Kids » National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

National Museum of American History

Grand Inquisitor » Larry Gates, National Museum of American History, SI

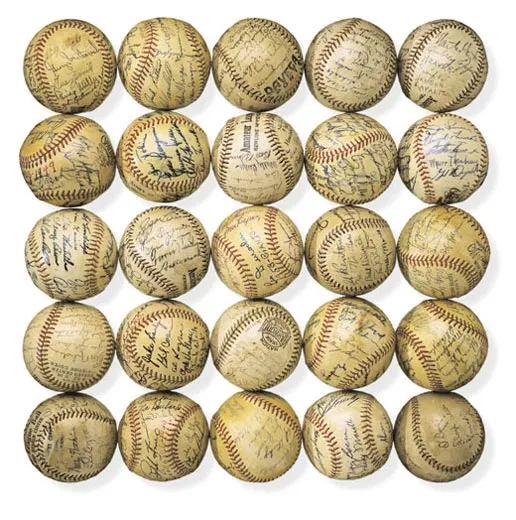

Power Balls » Eric Long, National Museum of American History, SI

National Museum of American History

Cast in Bondage » Eric Long / Smithsonian Institution

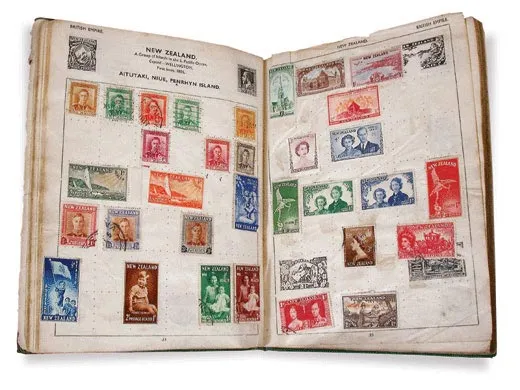

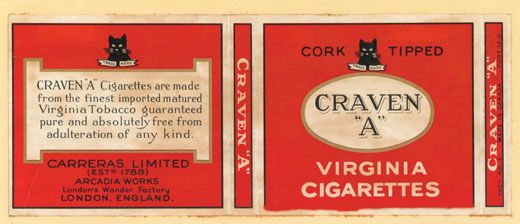

Pack Rat » Virgil Johnson Collection, Archives Center, NMAH, SI

Macho in Miniature » Hasbro, Inc.

It's a Wurlitzer » Eric Long/National Musuem of American History, SI

Sky King » Eric Long / NASM, SI

Under the Radar with Unmanned Aerial Vehicles » Eric Long / NASM

True to Form » Chip Clark

All that Glitters » Carol Channing Productions

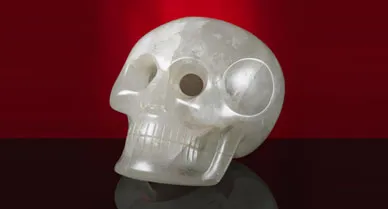

The Smithsonian's Crystal Skull » James Di Loreto/NMAH/SI

Golden Grail » Tom Mulvaney/ NMAH, SI

Ivory Merchant » National Museum of American History, SI

Spirals of History » Franko Khoury/ National Museum of African Art, SI

Breuer Chair, 1926 » Matt Flynn/ Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum

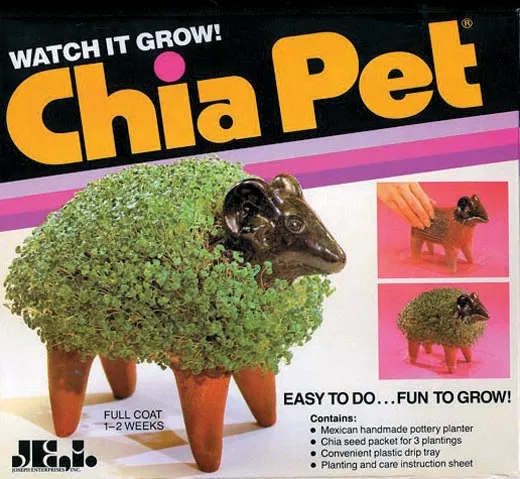

Growth Industry » Joseph Enterprises, Inc.

Benny Goodman's Clarinet » Bettmann / Corbis

Art and Soul » Bob Sapovits

Kitchen Aid » National Museum of the American Indian, SI

Baby Dell » Harold Dorwin, SI

The Flight Stuff » Mark Avino / NASM

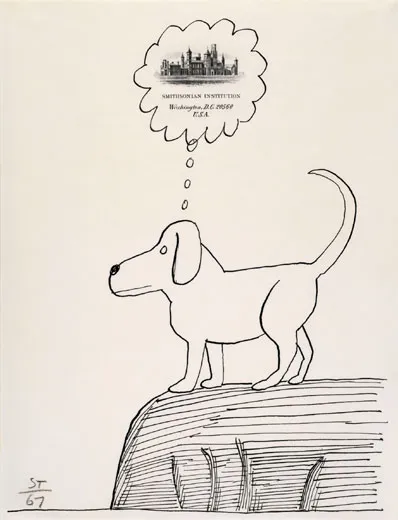

Doodle Dandy » Saul Steinberg / SAAM, SI

Flower Power » Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

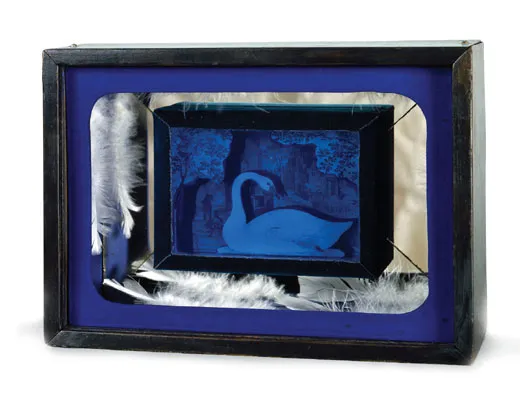

Pas de Deux » The Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation

Gathering Rosebuds » National Museum of the American Indian

Sacks Appeal » Matt Flynn / Cooper-Hewitt Museum, S.I.

Get the latest Travel & Culture stories in your inbox.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

Owen Edwards | READ MORE

Owen Edwards is a freelance writer who previously wrote the "Object at Hand" column in Smithsonian magazine.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)