A New Look at Anne Frank

Two comic book veterans—who authored the graphic adaptation of the 9/11 Report—train their talents on the young diarist

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/anne-frank-comic-book-631.jpg)

Forty years ago, Ernie Colón was drawing Casper the Friendly Ghost and Sid Jacobson was his editor at Harvey Comics, where they also churned out Richie Rich, Baby Huey and dozens of other titles. They worked together again at Marvel Comics (The Amazing Spider-Man, The Incredible Hulk) after Jacobson was named executive editor in 1987. Over time, they came to enjoy a close friendship and creative rapport while adhering to a fairly simple modus operandi. “I write the script,” Jacobson says, “and Ernie does the drawing.” Well, it’s not that simple, he adds. “There’s always the proviso that if you have a better way of doing it, please don’t follow what I’ve done.”

In recent years, their production has turned from the serials to the serious. Jacobson and Colón’s The 9/11 Report: A Graphic Adaptation, distilled the 9/11 Commission’s 600-page official findings into a more vivid and accessible form; it was a best seller in 2006. While the authors employed such familiar comic book devices as rendering sound effects (“BLAM!” go the 1998 bombings of U.S. embassies in East Africa), the graphic version was anything but kid stuff. It skillfully clarified a complex narrative, earning the enthusiastic blessing of the bipartisan commission’s leaders, Thomas H. Kean and Lee H. Hamilton. The book has found a niche in school curricula, as well. “It is required reading in many high schools and colleges today,” Jacobson says proudly.

When The 9/11 Report came out, there was “astonishment,” he says, at their groundbreaking use of graphic techniques in nonfiction. “But this was nothing new to us,” Jacobson says. “At Harvey Comics, we had a whole department on educational books. We did work for unions, for cities, we did one on military courtesy, for the Army and Navy. Early on, we saw what comics can be utilized for.”

***

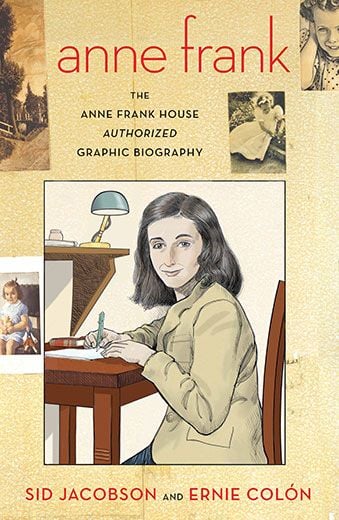

The authors’ latest work, published by Hill and Wang in September 2010, is similarly ambitious: Anne Frank, a graphic biography commissioned by the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam. For Jacobson, 81, and Colón, 79—a pair of politically aware grandfathers who both came of age in New York City in the 1940s—doing justice to the historical and psychological dimensions of the project summoned all their storytelling craft. As an example, Colón points to the challenge of rendering the much-mythologized figure of Anne as a credible, real-life child and adolescent. “I think the biggest problem for me was hoping that I would get her personality right, and that the expressions that I gave her would be natural to what was known of her or what I found out about her,” he says.

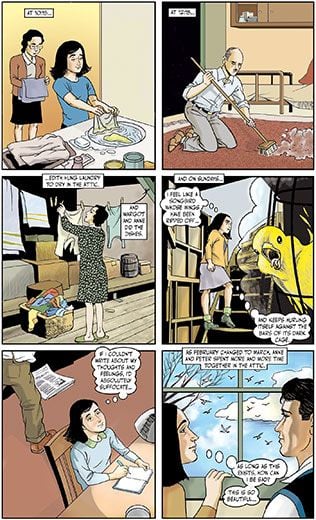

Two-thirds of the book takes place before or after the period Frank chronicled in her celebrated World War II diary, beginning with Anne’s parents’ lives before she was born. Their families had lived in Germany for centuries, and Anne’s father, Otto Frank, earned an Iron Cross as a German Army officer during World War I. Still, he was sufficiently alarmed by Hitler’s anti-Jewish fervor to seek safe haven for his family in the Netherlands soon after the Nazis took power in 1933. The refuge proved illusory. In 1940 the country was invaded, and the book’s middle chapters focus on the Franks’ two-year captivity in the secret annex of 263 Prinsengracht in Amsterdam, the crux of Anne’s Diary of a Young Girl (which she herself titled Het Achterhius, or The House Behind).

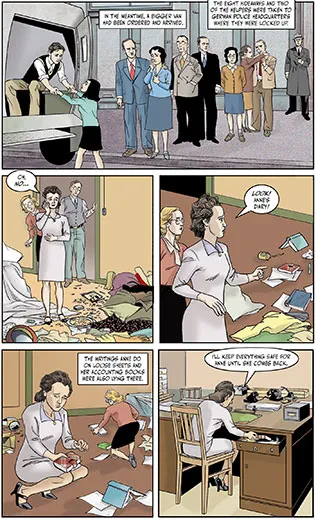

Unlike the diary, the graphic biography includes the aftermath: the family’s betrayal by a secret informer, their arrest and deportation, and their ordeals in Auschwitz, where Anne’s mother died, and Bergen-Belsen, where the emaciated Anne and her sister Margot succumbed to typhus in March 1945, just weeks before the camp’s liberation by British soldiers. The sole survivor, Otto, soon returned to Amsterdam, where he was given Anne’s journal by Miep Gies, one of the courageous Dutch citizens who had befriended and sheltered the Franks. Gies had placed the book in her desk for safekeeping, hoping to return it to Anne someday.

The biography concludes with material about the publication of the Diary, its popular adaptations for stage and film, and Otto’s lifelong determination to honor his daughter by committing himself “to fight for reconciliation and human rights throughout the world,” he wrote. He died in 1980, at the age of 91. (Miep Gies lived to 100; she died in January 2010.)

***

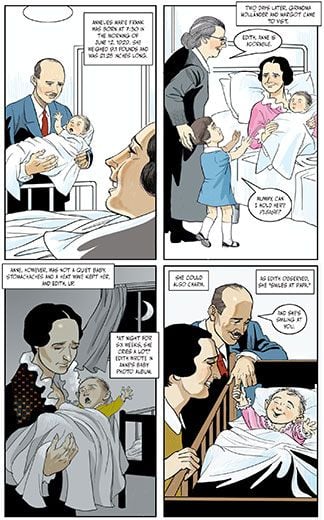

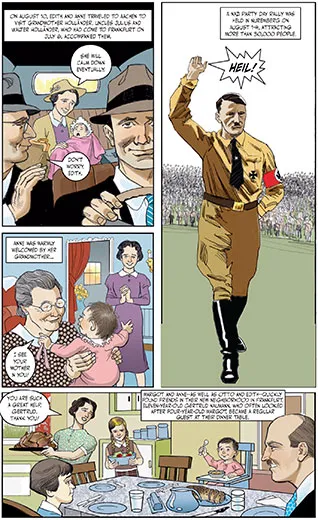

In counterpoint to the intimacy of Anne Frank’s family life, Jacobson and Colón weave in relevant themes from the larger historical context—the catastrophic rise and fall of Nazi Germany—creating a powerful narrative tension. Sometimes this is achieved in a single, well-executed stroke. On a two-page spread dwelling on the Franks’ joyous response to Anne’s birth in 1929, readers are confronted with a strongly vertical image of Hitler accepting a tumultuous heil at a mass rally in Nuremberg less than two months later. In a subtle visual touch, Hitler’s boot points directly down toward the much smaller image of the infant Anne, grinning sweetly in her high chair as the family prepares to eat supper—a tableau stretched across a page-wide horizontal panel. On one level, the abrupt intrusion of Hitler simply places the family story within the larger chronology; on another, it foreshadows the trampling of an innocent child’s happiness, and finally, her life. Fifteen years later, Anne would give voice to the dread the family came to feel. “I hear the approaching thunder that, one day, will destroy us too,” she wrote on July 5, 1944, three weeks before the Gestapo finally arrived.

With a solemn commitment to accuracy and authenticity, the authors immersed themselves in research, right down to the details of military uniforms, period furniture and political posters. Although Colón already considered himself a student of World War II, as he pored through thousands of photographs of the period, he found he was stunned anew. “We will never fully understand the descent into barbarity and deliberate sadism of the Nazi regime,” he said in a recent interview with CBR, a comics web site.

***

Anne Frank has inspired and fascinated people across generations and national boundaries, a phenomenon that shows little sign of waning. A steady flow of books and articles, films and plays continues, including an anime version of the Diary produced in Japan, where Anne is a hugely popular figure.

Objects associated with her have taken on the aura of holy relics. The house at 263 Prinsengracht receives a million visitors a year, more than two-thirds of whom are under the age of 30. Last August, when heavy winds felled the Anne Frank Tree—as the massive horse chestnut tree behind the house came to be known—the event sparked international headlines. “From my favorite spot on the floor I look up at the blue sky and the bare chestnut tree, on whose branches little raindrops shine, appearing like silver, and at the seagulls and other birds as they glide on the wind,” Anne wrote on February 23, 1944. Months later, she added: “When I looked outside right into the depth of nature and God, then I was happy, really happy.”

The tree that gave her solace did not die childless. Saplings have been distributed for replanting in dozens of sites around the world, including the White House, the National September 11 Memorial & Museum in Lower Manhattan, and Boise, Idaho, where a statue of Anne was erected in 2002 with the support of thousands of Idaho schoolchildren who held bake sales and other fundraisers. The monument was defaced with swastikas and toppled in 2007 before being reinstalled.

“She was murdered at the age of 15. Her figure is a romantic one, so for many reasons it’s not surprising that she’s the icon that she has become,” says Francine Prose, author of Anne Frank: The Book, The Life, The Afterlife (2009). Prose feels, however, that Anne’s canonization has obscured her literary talent.

“She was an extraordinary writer who left an amazing document of a terrible time,” Prose says, pointing to the many brilliant revisions Anne made in her own journal entries to sharpen the portraiture and dialogue. The seriousness with which she worked on her writing was not evident in the popular stage and screen versions of The Diary of Anne Frank, Prose believes. “The almost ordinary American teenaged girl Anne that appears in the play and the film are very different from what I finally decided was the genius that wrote that diary,” Prose says.

In the end, it was Anne Frank the person—not the larger-than-life symbol, but the individual girl herself—that touched Jacobson and Colón and made this project unique among the many they have undertaken. “It was amazingly meaningful for both of us,” says Jacobson, who was struck by the knowledge that he and Anne were born in the same year, 1929. “That became overwhelming to me,” he says. “To know that she died so young, and to think about the rest of the life that I’ve lived—that made me feel close to her.”

Colón remembered reading the Diary when it first came out. “I thought it was very nice and so forth,” he says. But this time around was different.

“The impact was just tremendous, because you really get to like this kid,” he says. “Here she is, persecuted, forced to hide and share a tiny room with a cranky, middle-aged man. And what was her reaction to all this? She writes a diary, a very witty, really intelligent, easy-to-read diary. So after a while you get not just respect for her, but you really feel a sense of loss.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jamie-Katz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jamie-Katz-240.jpg)