A Youth Renaissance for Native Americans

Filmmaker Chris Eyre says Native pride will embolden the next generation of first Americans

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Powwows-Chris-Eyre-631.jpg)

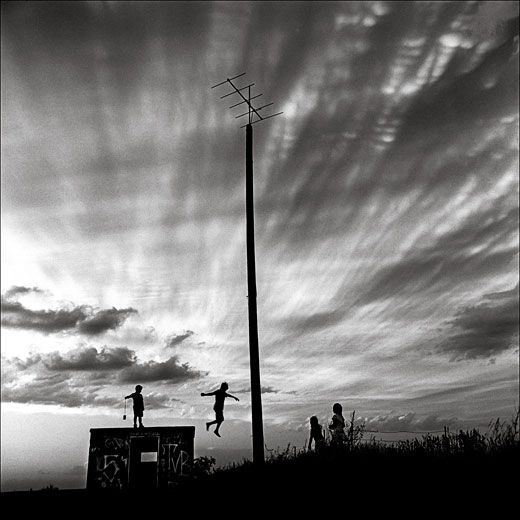

“Ooooh, look at that!” Shahela exclaims.

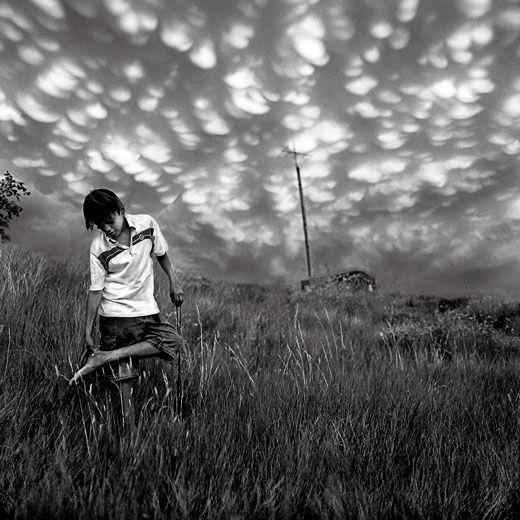

My daughter and I watch in fascination as an enormous grayish-purple cloud sweeps over the golden-brown rolling hills of the plains, cascades through the expansive sky and merges with the yellow horizon.

At that moment, I’m awe-struck by the power of the season changing from winter to spring, and I realize the spectacle would not be as beautiful without the dark gray cloud on the horizon.

I’m always inspired by the rebirth of the seasons. After I was born to my biological mother, Rose, of the Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes, I was reborn within days to my adopted parents, Barb and Earl, in a white middle-class home in Klamath Falls, Oregon. As a dark-skinned 5-year-old, I would ask my mom what I was going to be when I grew up.

“Anything you want!” she said.

“A fireman?”

“Yes!”

“What about president?”

“Yes!” she lied, lovingly. Or perhaps she had the foresight 30 years ago to think there would be a minority president.

As a Native American raised in a white environment, I have never seen things in black and white but always in many colors and shades of gray. I love singing country and western songs at karaoke, but I also love a good powwow and fry bread. Over the years, my work as an artist has always been about bridging the gap between the white world and the Native world. I then realized that it had already been done. There have been “Indian rednecks” for years.

I came to appreciate through my work that there are good people in both the Native and non-Native world. Though I also found that the American dream usually didn’t include my people, the Natives. For example, religious freedom for Natives to practice their own traditions was not legally upheld until 1994.

In the next 40 years, the greatest threat to Native tribal culture and tradition will be the American consumer ethic of personal economic gain at all costs. It runs deeply counter to the spirit of giving and codependence that is central to what we are as a people.

As more Native Americans participate in the wider economy through business initiatives such as gaming, we will also struggle with assimilation, a force that we have fought over the years. It was only about 20 years ago that the public at large allowed Indian gaming as a way to give back to the Indians. Ten years ago, I remember seeing a Native kid at a Southern California powwow driving his parents’ Hummer. A minority of tribes and their reservations have prospered from Indian gaming, but most still live in the same dire conditions.

Marginal cultures in the past have rightfully entered the mainstream through business, taking money from the majority and infusing it into their own tribes. It happened with Latinos, Asians and now Natives. It’s the American way. My greatest fear is that after all these years largely as nonparticipants in the American dream, our inclusion will ultimately kill off tribal languages, traditions and our knowledge.

Today, it is inspiring to see the number of strong Native American youth eager to learn more of our ancient traditions and cultures from the elders, who are more than happy to share with those who respect them. The youth renaissance is rooted, I think, in the elders’ tenacity, 1970s activism and a backlash against the mass media’s depiction of Native Americans.

The dismal portrayal of Native reservations is inaccurate and harmful. The media focus solely on poverty and the cycle of oppression. What most outsiders don’t see is the laughter, love, smiles, constant joking and humor and the unbreakable strength of the tribal spirit that is there. Some reservations are strongholds of community, serving the needs of their people without economic gain but with traditions leading the way. My hope is that Native evolution will be driven by a reinforced traditionalism passed down from one to another.

There is a calling not taught in religion or school; it is in one’s heart. It is what the tribe is about: to give to the cycle; to provide for those older and younger. My daughter knows it, just as she knows the natural beauty of seeing the clouds coming in the spring.

I love the gray rain.

Chris Eyre directed 1998’s Smoke Signals and three films in the 2009 PBS series “We Shall Remain.” Emily Schiffer founded a youth photography program on the Cheyenne River Reservation.