Explore Amazing Contributions Made by Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders with Four Smithsonian Stories

Celebrate Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander Heritage Month with Smithsonian objects

:focal(800x598:801x599)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/fa/72/fa726147-dbd0-4826-8acb-78f08f709fd6/smithsonian_voices_cover.jpg)

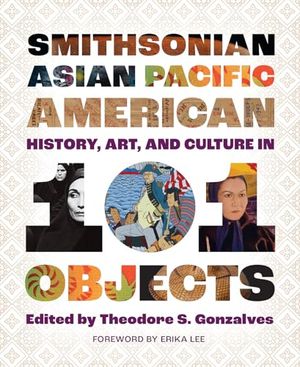

Since 1997, the US Census Bureau has understood the need to identify the distinct experiences between Asian Americans (“person[s] having origins in any of the original peoples of the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent”) and Native Hawaiians or other Pacific Islanders (or “person[s] having origins in any of the original peoples of Hawai‘i, Guam, Samoa, or other Pacific Islands”). Their histories in the Americas have been centuries in the making, and Smithsonian Asian Pacific American History, Art, and Culture in 101 Objects offers a window into the expanse of those stories. Today, we invite you into its pages with four amazing objects and stories.

1. Duke Kahanamoku’s Surfboard

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a1/7e/a17e86f9-a097-4a02-b424-bcd0162f45ea/duke_kahanamokus_surfboard.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b6/7a/b67a0428-f1fb-4a95-a507-9f7417a9a8e7/surfboard.jpg)

Born to a prominent family with direct ties to Hawaiian royalty, Duke Paoa Kahinu Moke Hulikohola Kahanamoku (1890–1968) advanced the world’s knowledge about surfing, a Pacific Islander practice dating back at least 1,500 years.

In his early twenties, Kahanamoku’s powerful swimming earned him an Olympic gold medal at the 1912 games in Stockholm for the 100-meter freestyle. Along with his two other Olympics appearances in 1920 and 1924, Kahanamoku would win a total of five medals—three gold and two silver.

With his international visits, especially to Australia and the United States, he became a cultural ambassador for surfing, helping to popularize it throughout the world. During a period of legalized segregation, he encountered racist treatment during his trip to the American South, which he met with his characteristic dignity and grace. Kahanamoku’s presence couldn’t be contained by America’s race codes. His celebrity continued to grow, as offers came to appear in more than a dozen films.

A year before he won his first gold medal, Kahanamoku penned an essay titled “Riding the Surfboard” in the inaugural issue of Mid-Pacific Magazine. He used powerful imagery to ask the reader: “How would you like to stand like a god before the crest of a monster billow, always rushing to the bottom of a hill and never reaching its base, and to come rushing in for half a mile at express speed, in graceful attitude, of course, until you reach the beach and step easily from the wave to the strand?”

Kahanamoku went into detail about the kinds of wood used in the making of Hawaiian surfboards—wiliwili, ulu, or koa—and the rituals involved in preparing a trunk for carving. Pohaku puna (coral) and oahi (stone) would be used for shaping the boards, while ti plant roots would be used for staining them. He shared his knowledge as he shaped boards for others around the world. The solid redwood surfboard in the Smithsonian’s collection has seen some incredible history. It was personally shaped by Kahanamoku at Corona del Mar for aerospace engineer Gerard (Jerry) Vultee in 1928. That’s the same year that Vultee would use the board in the Pacific Coast Surf Riding Championship, a milestone in the sport’s history.According to Paul Burnett, coauthor of Surfing Newport Beach: The Glory Days of Corona del Mar, this board is connected to a fantastic story. The dramatic event took place on June 14, 1925. The forty-foot fishing yacht, Thelma, capsized off the coast of Newport Beach, California. Kahanamoku and six others, including Vultee, jumped into action. While five persons drowned, twelve were rescued. Kahanamoku’s friends pulled four to safety while he was personally responsible for saving the lives of eight people over the course of three trips. A local police captain told the Los Angeles Times, “Duke’s performance was the most superhuman rescue act and the finest display of surfboard riding that has ever been seen in the world.” When asked how Kahanamoku accomplished the feat, Duke said: “I do not know. It was done. That is the main thing. By a few tricks, perhaps.” This board was used in what has come to be known as the Great Rescue of 1925. —Theodore S. Gonzalves

2. Stella Abrera's Ballet Shoes

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d5/2c/d52c6bf2-2b85-4b6c-885c-64b1a10a9e2f/stella_abreras_ballet_shoes.jpg)

In 1996, at the age of seventeen, Abrera joined ABT as an apprentice after a successful audition. She would go on to rise in the ranks at ABT, earning the role of principal in 2015—the first Filipina American ballerina in the company to do so. However, Abrera’s journey to becoming principal was not conventional, nor was it easy. Abrera was promoted to soloist in 2001, but a serious sciatic nerve injury in 2008 took Abrera out of dancing for two years. Abrera recalls the difficulty of recovery and having to relearn the way she danced at the age of thirty.

Fortunately, Abrera was able to return as a soloist, and she saw her recovery as a miracle. She recalled in an interview that the announcement of her promotion to principal was “magic,” where all the struggles and triumphs she faced in the years leading up to that point were a “gift." Abrera remained with ABT until her retirement in 2020.

The ballet shoes shown here were worn by Abrera in an October 2017 production of Daphnis et Chloé. The shoes would have been worn for rehearsals for this show and likely for only one performance, perhaps two. They have been “pancaked” to match Abrera’s skin tone. Dancers often coat their pointe shoes with makeup, known as pancaking, when they are not wearing tights, in order for the shoes to match their skin color. The process varies for each dancer, but it usually involves applying a thin layer to the shoe to cover up the shine, which can take up to ten to fifteen minutes when done with care.

Abrera’s shoes are reflective of ABT’s effort to promote diversity in the company. Speaking about the significance of her role as principal to young Asian American women, Abrera mentions how much representation matters. People of different skin colors are actively being encouraged to be part of ballet, and companies continue to evolve to attract diverse performers and audiences. —Thanh Lieu

Smithsonian Asian Pacific American History, Art, and Culture in 101 Objects

A rich and compelling introduction to the history of Asian Pacific American communities as told through 101 objects, from a fortune cookie baking mold to the debut Ms. Marvel comic featuring Kamala Khan

3. Hari Govind Govil's Patent

In 1937, an Indian man, Hari Govind Govil (1899–1956) patented the typeface of a complex font for Linotype that would facilitate the entry of Hindu culture to the West while bringing major changes to the publishing and newspaper industry in South Asia.Govil’s 1937 patent would eventually allow Linotype machines to print Devanagari, a dominant script of South Asia that, by 1950, would be considered the official script of the Union of India. Newspaper articles hailed this development as a stride for increasing the literacy of one-sixth of the world’s population. Before the era of computers, machines like the Linotype were the key to advancing knowledge through the printed word. But before this achievement could take place, Govil had to embark on a journey far from home.

As a university student in Benares, Govil was ambitious, but unhappy with the traditional style of education in India. He decided to travel to the United States, hoping to benefit from what he viewed as a more flexible and innovative culture. In the process, his perspective on India and its connections to the West gained both depth and breadth.

The 1917 Immigration Act passed by Congress created a large “Asiatic barred zone” stretching from the Middle East to Southeast Asia in order to exclude South Asians from migrating to the United States. The act made exceptions for certain professions as well as for students, allowing Govil to make his way.

Soon after his arrival in the US in 1920, Govil began several years of correspondence with his hero back home, Mohandas Gandhi, who had been sharpening the tactics of nonviolent noncooperation against the British. In 1922, Gandhi provided encouragement to the young student: “Every worker abroad [such as yourself] who endeavors to study the movement and interpret it correctly helps it.”

Govil secured a position at the Mergenthaler Linotype Company in New York, and became fascinated with the technology—both its potential to enhance education and the written arts, and to facilitate cultural and political exchange. Govil designed his type with interchangeable parts, so that it could be used to compose text in related South Asian languages, such as Hindi, Gujarat, Bengali, Behari, Nepali, and Jaina.

Govil became a proponent for Indian nationalism. Soon after he received the note from Gandhi, Govil penned an editorial for an American audience, announcing that a new chapter of world history would be marked by the Indians’ adoption of Gandhian nonviolence.

In 1924, Govil established the India Society of America, Inc., in New York City, surrounding himself with support from an impressive cross section of advisors, including missionary/educator Sidney L. Gulick, ACLU cofounder Jane Addams, choreographer Ruth St. Denis, journalist Heywood Broun, NAACP cofounder Oswald Garrison Villard, and philosopher/education reformer John Dewey, among many others. With Govil at the helm, the society launched several well-publicized activities “to promote cultural relations between India and America,” including lectures, receptions, art exhibits, film screenings, radio programming, and publications.

Writing for the Hindustan Review at the society’s founding, a fellow Indian nationalist, V. V. Oak—also living in the United States at the time—suggested that Govil’s tactical use of culture and the arts was the right means to achieve the ends of Indian nationalism.

In 1929, Govil appeared to echo Oak’s sentiments by observing that India’s “spiritual achievement” was just as significant as any scientific achievement by the West. The creation of a simple font forged the link he sought. In the same year that Govil applied for his patent, the Times of India quoted his aims: to create a “uniform method of writing, and I think this would wield her [India] together.” —Theodore S. Gonzalves

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/72/04/72048173-1d83-4c50-8203-6c9412be4c35/wok.jpg)

4. Wok

Joseph Becker’s 1870 illustration of a Chinese railroad work camp offered a glimpse into a quiet moment at the end of a long day of repetitive and dangerous work. The drawing was titled “The Coming Man—A Chinese Camp Scene on the Line of the Central Pacific Railroad,” and it appeared in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. The accompanying text stated:Their staple article of diet was boiled rice, but they were by no means averse to fish, flesh and fowl, when they could get them. Their cooking was generally performed in broad pans, which they turned one above the other, in case they wished to keep the steam inside. When their meals were ready they squatted on the ground, and performed some very lively work with their chopsticks. For an inexperienced person to eat rice with chopsticks is much like taking soup with a fork; but a Chinese finds no difficulty in getting a large quantity down his throat, and at a very rapid rate.

Chinese railroad laborers worked in gangs of about a dozen; each unit had a cook and a leader. Many toiled and lived in isolated settings, never too far from where the tracks were being laid. Out west, Chinese workers were hired as railroad laborers as early as 1858. Six years later, they were hired by the Central Pacific Railroad and would be indispensable in the creation of the 1,911-mile transcontinental railroad. Historians estimate that 10,000 to 15,000 Chinese workers joined the effort—clearing land, moving snow, and boring tunnels. Some of the most dangerous tasks involved setting dynamite charges to create mountain passages for the iron road. While capital welcomed their Chinese labor, nativists increasingly pushed for segregation and eventually legal exclusion.In the background of Becker’s image, two tents are set up with a person setting up a third. The cook is in the foreground, tending to two large woks, both set directly on the ground with fires beneath. One is covered, most likely to steam vegetables. The other appears to be filled with fish perhaps caught in a nearby lake, arranged in a single layer. He’s keeping an eye on his shallow frying, with a spatula in his left hand.

Archivists point to evidence that Chinese workers had a varied diet, even as they lived thousands of miles from home. Customs invoices report items such as dried fruits, dried oysters, shrimps, cuttle fish, mushrooms, dry bean curd, bamboo shoots, sausage, and ginger being imported to sell to the Chinese workers. Other receipts list tools such as knives, chopsticks, and ladles. For all these ingredients and staples, storage containers and cookware were needed, including the all-important wok.The skills that the cooks developed out on those remote camps became essential for the thousands of others who would continue their journeys across the Pacific. Decades later, many of those experiences were distilled into guidebooks published in Chinese American communities like Cui Tongyue’s Hua Ying Chu Shu Da Quan (Chinese English Comprehensive Cookbook). As historian Yong Chen explains, this was more than a travel guide for the casual visitor. A book like this functioned like an atlas for newcomers, including tips for how to travel by rail or steamship, recipes for American dishes, a glossary of food words, and simulated dialogues for how to negotiate a higher wage. For example, here’s an exchange from Tongyue’s “cookbook.”

Q: “What were you paid per month?”A: “Twenty-five dollars. That is not enough for me.”

Q: “How much do you want?”A: “Forty-five dollars.”

The cookbook, like the humble wok and the workers, are part of complex labor histories. —Theodore S. GonzalvesSmithsonian Asian Pacific American History, Art, and Culture in 101 Objects edited by Theodore S. Gonzalves is available from Smithsonian Books. Visit Smithsonian Books’ website to learn more about its publications and a full list of titles.

Excerpt from Smithsonian Asian Pacific American History, Art, and Culture in 101 Objects © 2023 by Smithsonian Institution

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.